Christian Rohlfs, (German, 1849-1938)

Tänzerin mit Schleier

Tänzerin mit Schleier

signed with the artist initials and dated 'CR 28' (lower right)

oil on canvas

67.8 x 52.8cm (26 11/16 x 20 13/16in).

Painted in 1928

Provenance

Helene Rohlfs Collection (the artist's widow).

Private collection, Southern Germany.

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2012.

Exhibited

Berlin, Galerie Ferdinand Möller, Ausstellung Christian Rohlfs der Galerie Ferdinand Möller, December 1928 - January 1929, no. 16 (titled 'Tänzerin').

Kiel, Kunsthalle zu Kiel, Schleswig-Holsteinischer Kunstverein, Christian Rohlfs, May - June 1930, no. 34 (titled 'Tänzerin').

Leverkusen, Farbenfabriken Bayer Aktiengesellschaft, Christian Rohlfs, Gemälde, Tempera-Blätter, Zeichnungen und Graphik, 1955 - 1956, no. 31 (later travelled to Essen, Munich, Karlsruhe & Lübeck; titled 'Tänzerin').

Darmstadt, Kunstverein Darmstadt e. V., Kunsthalle am Steubenplatz, Christian Rohlfs, Das Spätwerk, 30 January - 6 March 1960, no. 24.

Hamm, Gustav Lübcke Museum, Genuss. Empfindung. Aufbegehren. Menschenbilder im Expressionismus, 16 September 2012 - 24 March 2013.

Literature

P. Vogt (ed.), Christian Rohlfs, Oeuvre-Katalog der Gemälde, Recklinghausen, 1978, no. 725 (illustrated n. p.).

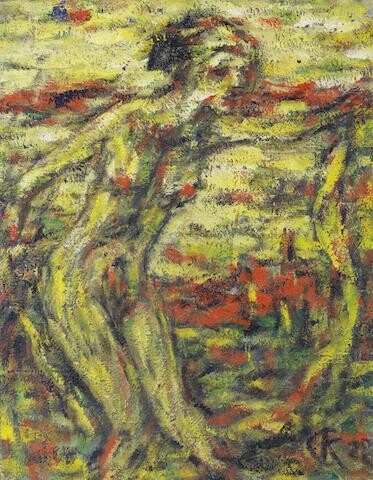

Executed in the later part of Christian Rohlfs' career, Tänzerin mit Schleier bears testimony to his perpetual quest for authenticity in his art, and his eagerness to involve himself with the new generation of young Expressionist artists in the early twentieth century. The vitality tangible in Rohlfs' work from this period can be attributed in part to his marriage to Helene in 1919 at the age of 70. Prior to this point Rohlfs worked largely from his studio in Hagen, however the union with his young bride prompted a desire for travel, alongside a predilection for colour and luminosity which hitherto had not been present within his paintings. This new sense of expressive abandonment and delight in pure colour caught the eye of various institutions and museums and Rohlfs began to garner new-found public recognition and success: 'Exhibitions were held in increasing numbers... his own regional University in Keil conferred honorary doctorates upon him, he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin and an honorary citizen of Hagen, where a street and the newly founded museum were named after him' (P. Vogt, Christian Rohlfs 1849 1938: The Later Works, (exh. cat), Essen, 1965 1966, n. p.).

In 1927, a year before the execution of the present work, Rohlfs made his first trip to the south of Europe, travelling to Ascona on Lake Maggiore where he was later to return year after year. His experience of the intensity of light had a profound effect upon his art, in which colour 'lost its material importance and became a delicate, intangible web, permeating his greatest compositions with a kind of inner light' (P. Vogt, ibid, n. p.). This pervasive and non-naturalistic use of colour is excellently manifested in Tänzerin mit Schleier, in which Rohlfs realises both his subject and background through a concatenation of acid greens and yellows shot through with vermillion accents. Blurring the boundaries between form and colour, Rohlfs defines his dancing subject and the rooftops beyond through the merest suggestions of form and contour. The non-representational use of colour here accords with Expressionist aesthetics, yet the use of the same colour palette throughout the canvas further minimises the representational qualities of the composition and flattens the picture space, foregrounding gesture and surface texture in a daringly abstract manner.

Indeed, the method by which Rohlfs developed the application of his paint served to emphasise the expressive effects of his work. By building up layers of colour upon the canvas through the broad strokes of a spatula he liberated his handling, realising bold, radical marks which gesture towards abstraction. It was also in his use of tempera that he was able to achieve a transparency and purity of colour which surpassed the chromatic effects of oils. Never mixing the paint on the palette, Rohlfs preferred instead to apply the pure pigment directly to the wet ground of the support, building gauzy, textural layers of colour and luminosity.

The nude subject en plein air and her dynamic pose immediately bring to mind the bathers and dancers so beloved of the Expressionists, and more specifically those of the Brücke group who included Kirchner, Pechstein and Schmidt-Rottluff. Though Rohlfs was not a member of Die Brücke or Der Blaue Reiter he exulted in the new techniques that they pioneered and shared their aims to 'counter the spiritual disintegration of a technical age by the return to the elementary forces' (U. Von Pückler, Christian Rohlfs (1849 1938), The text of a Lecture given at City of York Art Gallery on May 11th 1956, York, 1956, p. 7). In Expressionist discourse the bather/ dancer subject came to signify an antimodernist motif in which nudism and the dancing arenas of the circus or cabaret posed a liberated, even primitive space. For Rohlfs, resolutely experimental despite being a contemporary of Renoir, Expressionism provided the means through which he could convey his personal vision of the world - namely the elemental and spiritual forces which lay beyond the purely optical.

Tänzerin mit Schleier in form and subject encapsulates Rohlfs' unique perception of the visual world, 'as a slowly unfolding pattern of growth and decay' (H. Hess, Paintings by Christian Rohlfs 1849 1938, (exh. cat), London, 1956, n. p.). The colours, at once bodily and vegetal, are complimented by a surface texture which bristles with verve and expressive force. Rohlfs was the only artist of his generation to be whole-heartedly recognised and accepted by the younger generation of Expressionist artists, and his later work (despite being destroyed in large part by the Nazis) remains a key example of the German Expressionist movement today.

View it on

Sale price

Time, Location

Auction House

Tänzerin mit Schleier

Tänzerin mit Schleier

signed with the artist initials and dated 'CR 28' (lower right)

oil on canvas

67.8 x 52.8cm (26 11/16 x 20 13/16in).

Painted in 1928

Provenance

Helene Rohlfs Collection (the artist's widow).

Private collection, Southern Germany.

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2012.

Exhibited

Berlin, Galerie Ferdinand Möller, Ausstellung Christian Rohlfs der Galerie Ferdinand Möller, December 1928 - January 1929, no. 16 (titled 'Tänzerin').

Kiel, Kunsthalle zu Kiel, Schleswig-Holsteinischer Kunstverein, Christian Rohlfs, May - June 1930, no. 34 (titled 'Tänzerin').

Leverkusen, Farbenfabriken Bayer Aktiengesellschaft, Christian Rohlfs, Gemälde, Tempera-Blätter, Zeichnungen und Graphik, 1955 - 1956, no. 31 (later travelled to Essen, Munich, Karlsruhe & Lübeck; titled 'Tänzerin').

Darmstadt, Kunstverein Darmstadt e. V., Kunsthalle am Steubenplatz, Christian Rohlfs, Das Spätwerk, 30 January - 6 March 1960, no. 24.

Hamm, Gustav Lübcke Museum, Genuss. Empfindung. Aufbegehren. Menschenbilder im Expressionismus, 16 September 2012 - 24 March 2013.

Literature

P. Vogt (ed.), Christian Rohlfs, Oeuvre-Katalog der Gemälde, Recklinghausen, 1978, no. 725 (illustrated n. p.).

Executed in the later part of Christian Rohlfs' career, Tänzerin mit Schleier bears testimony to his perpetual quest for authenticity in his art, and his eagerness to involve himself with the new generation of young Expressionist artists in the early twentieth century. The vitality tangible in Rohlfs' work from this period can be attributed in part to his marriage to Helene in 1919 at the age of 70. Prior to this point Rohlfs worked largely from his studio in Hagen, however the union with his young bride prompted a desire for travel, alongside a predilection for colour and luminosity which hitherto had not been present within his paintings. This new sense of expressive abandonment and delight in pure colour caught the eye of various institutions and museums and Rohlfs began to garner new-found public recognition and success: 'Exhibitions were held in increasing numbers... his own regional University in Keil conferred honorary doctorates upon him, he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin and an honorary citizen of Hagen, where a street and the newly founded museum were named after him' (P. Vogt, Christian Rohlfs 1849 1938: The Later Works, (exh. cat), Essen, 1965 1966, n. p.).

In 1927, a year before the execution of the present work, Rohlfs made his first trip to the south of Europe, travelling to Ascona on Lake Maggiore where he was later to return year after year. His experience of the intensity of light had a profound effect upon his art, in which colour 'lost its material importance and became a delicate, intangible web, permeating his greatest compositions with a kind of inner light' (P. Vogt, ibid, n. p.). This pervasive and non-naturalistic use of colour is excellently manifested in Tänzerin mit Schleier, in which Rohlfs realises both his subject and background through a concatenation of acid greens and yellows shot through with vermillion accents. Blurring the boundaries between form and colour, Rohlfs defines his dancing subject and the rooftops beyond through the merest suggestions of form and contour. The non-representational use of colour here accords with Expressionist aesthetics, yet the use of the same colour palette throughout the canvas further minimises the representational qualities of the composition and flattens the picture space, foregrounding gesture and surface texture in a daringly abstract manner.

Indeed, the method by which Rohlfs developed the application of his paint served to emphasise the expressive effects of his work. By building up layers of colour upon the canvas through the broad strokes of a spatula he liberated his handling, realising bold, radical marks which gesture towards abstraction. It was also in his use of tempera that he was able to achieve a transparency and purity of colour which surpassed the chromatic effects of oils. Never mixing the paint on the palette, Rohlfs preferred instead to apply the pure pigment directly to the wet ground of the support, building gauzy, textural layers of colour and luminosity.

The nude subject en plein air and her dynamic pose immediately bring to mind the bathers and dancers so beloved of the Expressionists, and more specifically those of the Brücke group who included Kirchner, Pechstein and Schmidt-Rottluff. Though Rohlfs was not a member of Die Brücke or Der Blaue Reiter he exulted in the new techniques that they pioneered and shared their aims to 'counter the spiritual disintegration of a technical age by the return to the elementary forces' (U. Von Pückler, Christian Rohlfs (1849 1938), The text of a Lecture given at City of York Art Gallery on May 11th 1956, York, 1956, p. 7). In Expressionist discourse the bather/ dancer subject came to signify an antimodernist motif in which nudism and the dancing arenas of the circus or cabaret posed a liberated, even primitive space. For Rohlfs, resolutely experimental despite being a contemporary of Renoir, Expressionism provided the means through which he could convey his personal vision of the world - namely the elemental and spiritual forces which lay beyond the purely optical.

Tänzerin mit Schleier in form and subject encapsulates Rohlfs' unique perception of the visual world, 'as a slowly unfolding pattern of growth and decay' (H. Hess, Paintings by Christian Rohlfs 1849 1938, (exh. cat), London, 1956, n. p.). The colours, at once bodily and vegetal, are complimented by a surface texture which bristles with verve and expressive force. Rohlfs was the only artist of his generation to be whole-heartedly recognised and accepted by the younger generation of Expressionist artists, and his later work (despite being destroyed in large part by the Nazis) remains a key example of the German Expressionist movement today.