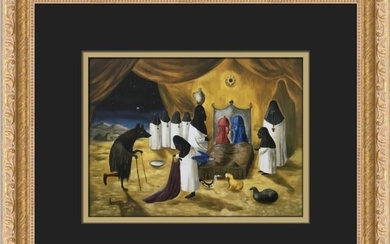

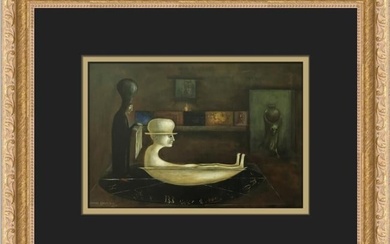

LEONORA CARRINGTON, (1917-2011)

Operation Wednesday

Operation Wednesday

signed and dated 'Leonora Carrington March 1969' (lower left) and extensively inscribed (to the foreground); signed, inscribed and dated 'Operation Wednesday, Dr. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio., Leonora Carrington, March 1969.' (on the reverse)

oil and tempera on board

61.1 x 45.1cm (24 1/16 x 17 3/4in).

Painted in March 1969

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by Dr. Salomon Grimberg. This work will be included in the forthcoming Leonora Carrington catalogue raisonné of paintings, currently being prepared by Dr. Grimberg.

Please note that this work has been requested for an upcoming Leonora Carrington exhibition at the Arken Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, 17 September 2022 – 15 January 2023, later travelling to the Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid, 8 February – 14 May 2023.

Provenance

Dr. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio Collection, Mexico City (acquired directly from the artist).

Thence by descent from the above; their sale, Sotheby's, New York, 28 May 2013, lot 29.

Private collection, US (acquired at the above sale).

Exhibited

Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Leonora Carrington, The Celtic Surrealist, 18 September 2013 – 26 January 2014 (later travelled to San Francisco).

Liverpool, Tate, Leonora Carrington, Transgressing Discipline, 6 March – 31 May 2015.

San Francisco, Gallery Wendi Norris, Threads of Memory, One Thousand Ways of Saying Goodbye, 21 October – 15 November 2017.

Mexico City, Museo de Arte Moderno, Leonora Carrington Magical Tales, 21 April – 23 September 2018, no. 68 (later travelled to Monterrey).

New York, Gallery Wendi Norris, Leonora Carrington, The Story of the Last Egg, 23 May - 29 June 2019.

The painting Operation Wednesday (1969) by Surrealist artist and writer Leonora Carrington (1917-2011), is a work that presents a wonderful fusion of Christian, Mayan, and esoteric symbolism. It also marks a critical decade in Carrington's career when her art increasingly took on a socio-political message, demonstrating a firm allegiance to her adopted homeland, Mexico, where she had lived since 1943.

The title is deceptively simple and its caption, written on the work in Spanish, reveals more: 'no olvides Tlatelolco.. les tres culturas,,, no tenernos tumba... campo military número 1' (Don't forget Tlatelolco... the three cultures...we don't fear the grave... military camp number 1)." These words make clear that Carrington's painting pays homage to the student movement or Movimiento Estudiantil, led by the students and staff of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM), which began on July 22, 1968. She commemorates those killed and injured in the massacre in Plaza de las Tres Culturas (Plaza of the Three Cultures) in Mexico City on Wednesday October 2, 1968, and those rounded up, detained and tortured in Military Camp One.

On October 2, 1968, ten thousand students gathered in the Plaza in Tlatelolco to begin a peaceful protest march through the city only to find themselves surrounded by Federal troops, many in tanks, who opened fire as night fell. They were protesting against the nation's one party government under Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and the lack of political freedom; he in turn was determined to quash months of student protests, especially in the lead up to the opening of the Olympic Games, scheduled for 12 October. Some 200-400 protestors, innocent bystanders, children (the precise number has never been firmly established) were killed, an estimated two thousand students rounded up, imprisoned, beaten and tortured. In her book documenting this massacre, Elena Poniatowska writes of October 2, 1968: 'There are many. They come down Melchor Ocampo, the Reforma, Juárez, Cinco de Mayo, laughing, students walking arm in arm in the demonstration [...] carefree boys and girls who do not know that tomorrow and the day after, their dead bodies will be lying swollen in the rain.'1

Carrington's own sons, Gabriel and Pablo, were involved in the student protests and had been printing anti-government propaganda leaflets and posters on the mimeograph belonging to their father, the Hungarian photographer Emerico 'Chiki' Weisz (1911-2007), in their family home. Carrington asked Gabriel to introduce her to his student circle in the aftermath of the massacre and together they planned a silent protest by marching through the city centre, all dressed in black. However, soon she and her family were in danger of arrest too: one morning they received a phone call warning them that the writer Elena Garro had denounced Carrington and Gabriel to the police; they quickly arranged to leave the country, flying to New Orleans, where they stayed until Chiki advised them it was safe to return.2

In addition to commemorating the student protestors, Carrington's painting pays homage to those who supported and saved some of the wounded students, notably Dr Fernando Ortiz Monasterio (1923-2012), to whom the painting is dedicated. Monasterio's 'operation' was radically different to Díaz Ordaz's oppressive regime, of course. He is presented as a medical and humanitarian shaman. He dominates the composition in his tall slender form as the healer at a time of military terror, or an intermediary between a violent moment in history and a better future. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio was a surgeon and teacher who specialized in cranio-facial surgery, assisting many children born with facial abnormalities or suffering tumours. He worked for the Ministry of Health in Mexico and was affiliated with the Graduate Division of UNAM as well as the Hospital General Gea Gonzalez, in the Tlalpan district. Monasterio was known for his interest in music, literature, anthropology and sociology, and for his determination to understanding how and why so many Mexican children were born with cranial deformations.3

Carrington's choice of medium for this work also pays homage to the humanism and skill of the doctor. She uses egg tempera, a technique which involves an emulsion of pigment and a water soluble binder – here the binder is egg yolk. Whilst a difficult process, prone to dry flaking, tempera had great symbolic significance in bringing art and science, the feminine (symbolised by the egg) and the masculine (the technical skill), together. Tempera and temperament share a common Latin root - temperare, to mix - and both involve the binding of things whether humors and tempers or pigments. In being associated with the feminine, her choice of tempera technique also serves as a striking counterpoint to the mechanical violence of the massacre. Tempera speaks to an old, life-giving process through the alchemical symbolism of the egg and by extension may be read as a means to challenge an emphatically modern, masculinist, political regime. Tempera was a popular medium in Surrealist circles, especially for women painters, and once Carrington moved to Mexico in 1943 it became a staple technique in her studio there. One friend described her studio as a 'narrow little room in old Mexico, the most dream-saturated place I know here'.4

Carrington's recourse to diverse cultural symbols ensures the viewer is intrigued by her use of dramatic colour and detail alike and searches out the stories behind them. We find English and Spanish text in the foreground, some of it in mirror writing; a palette dominated by bands of white and black - the doctor and his assistant are in white which symbolises light, and the androgynous patient they assist is dressed in a black cloak, the colour of which symbolises darkness and mourning. The colour red links further details, notably the patient's Cyclopean red eye and the dove's blood, which the small skeleton uses as ink. Here Carrington evokes traditional Christian symbolism as the skeleton traditionally denotes the inevitability of death, as in a memento mori. The diminutive size of the skeleton may also suggest children - those killed and wounded in the massacre, those assisted by the doctor, and the child who embodies the future of Mexico. The specificity of the historical moment is marked by the words of healing on the book the skeleton holds: 'WE HANGED / OUR HARPS / CARRIED / US'. Fittingly, the words refer to a communal lament and yearning for Jerusalem as well as a hatred for those that would destroy it - 'we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof'.5 Carrington's reference to these words suggests that the time for music has gone, instruments have been put away, and only the sound of mourning remains. The foot of the black cloaked figure in her painting reinforces this message in drawing the viewer's eye to multiple white crosses, denoting victims, as well as the red script in backward, mirror writing, which reads 'Thou hearest not, and in the night season, am not silent, Oh, my God, I cry'.6

But all is not lost, even if faith is challenged, merriment suspended and a rebellion cruelly halted. Carrington brings a ray of hope into the scene: red links the all-seeing eye of the patient and the blood of the bird and the biblical words, while in alchemical terms, red denotes sulphur or the final stage in the alchemical process as a base metal like lead (black, nigredo) turns through silver (white, albedo) to gold (red, rubedo), connoting success or rebirth. Carrington frequently fused references to European occultism (Spiritualism, Tarot, Tibetan Buddhism) with Mexican tradition (shamanism, rituals involving peyote or love potions, and the Mayan creation myth as articulated in the sixteenth-century text Popol Vuh). She magnifies the import of the massacre at Tlatelolco and its commemoration through further details which draw on Mayan culture: the blue rose symbolising sacrifice, the blue butterfly symbolising the spirit of deceased warriors, and the golden apple symbolising immortality.

The ghostly figure of a hummingbird above the doctor further alludes to the Mayans, for whom the bird was sacred and had healing...

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Operation Wednesday

Operation Wednesday

signed and dated 'Leonora Carrington March 1969' (lower left) and extensively inscribed (to the foreground); signed, inscribed and dated 'Operation Wednesday, Dr. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio., Leonora Carrington, March 1969.' (on the reverse)

oil and tempera on board

61.1 x 45.1cm (24 1/16 x 17 3/4in).

Painted in March 1969

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by Dr. Salomon Grimberg. This work will be included in the forthcoming Leonora Carrington catalogue raisonné of paintings, currently being prepared by Dr. Grimberg.

Please note that this work has been requested for an upcoming Leonora Carrington exhibition at the Arken Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, 17 September 2022 – 15 January 2023, later travelling to the Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid, 8 February – 14 May 2023.

Provenance

Dr. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio Collection, Mexico City (acquired directly from the artist).

Thence by descent from the above; their sale, Sotheby's, New York, 28 May 2013, lot 29.

Private collection, US (acquired at the above sale).

Exhibited

Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Leonora Carrington, The Celtic Surrealist, 18 September 2013 – 26 January 2014 (later travelled to San Francisco).

Liverpool, Tate, Leonora Carrington, Transgressing Discipline, 6 March – 31 May 2015.

San Francisco, Gallery Wendi Norris, Threads of Memory, One Thousand Ways of Saying Goodbye, 21 October – 15 November 2017.

Mexico City, Museo de Arte Moderno, Leonora Carrington Magical Tales, 21 April – 23 September 2018, no. 68 (later travelled to Monterrey).

New York, Gallery Wendi Norris, Leonora Carrington, The Story of the Last Egg, 23 May - 29 June 2019.

The painting Operation Wednesday (1969) by Surrealist artist and writer Leonora Carrington (1917-2011), is a work that presents a wonderful fusion of Christian, Mayan, and esoteric symbolism. It also marks a critical decade in Carrington's career when her art increasingly took on a socio-political message, demonstrating a firm allegiance to her adopted homeland, Mexico, where she had lived since 1943.

The title is deceptively simple and its caption, written on the work in Spanish, reveals more: 'no olvides Tlatelolco.. les tres culturas,,, no tenernos tumba... campo military número 1' (Don't forget Tlatelolco... the three cultures...we don't fear the grave... military camp number 1)." These words make clear that Carrington's painting pays homage to the student movement or Movimiento Estudiantil, led by the students and staff of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM), which began on July 22, 1968. She commemorates those killed and injured in the massacre in Plaza de las Tres Culturas (Plaza of the Three Cultures) in Mexico City on Wednesday October 2, 1968, and those rounded up, detained and tortured in Military Camp One.

On October 2, 1968, ten thousand students gathered in the Plaza in Tlatelolco to begin a peaceful protest march through the city only to find themselves surrounded by Federal troops, many in tanks, who opened fire as night fell. They were protesting against the nation's one party government under Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and the lack of political freedom; he in turn was determined to quash months of student protests, especially in the lead up to the opening of the Olympic Games, scheduled for 12 October. Some 200-400 protestors, innocent bystanders, children (the precise number has never been firmly established) were killed, an estimated two thousand students rounded up, imprisoned, beaten and tortured. In her book documenting this massacre, Elena Poniatowska writes of October 2, 1968: 'There are many. They come down Melchor Ocampo, the Reforma, Juárez, Cinco de Mayo, laughing, students walking arm in arm in the demonstration [...] carefree boys and girls who do not know that tomorrow and the day after, their dead bodies will be lying swollen in the rain.'1

Carrington's own sons, Gabriel and Pablo, were involved in the student protests and had been printing anti-government propaganda leaflets and posters on the mimeograph belonging to their father, the Hungarian photographer Emerico 'Chiki' Weisz (1911-2007), in their family home. Carrington asked Gabriel to introduce her to his student circle in the aftermath of the massacre and together they planned a silent protest by marching through the city centre, all dressed in black. However, soon she and her family were in danger of arrest too: one morning they received a phone call warning them that the writer Elena Garro had denounced Carrington and Gabriel to the police; they quickly arranged to leave the country, flying to New Orleans, where they stayed until Chiki advised them it was safe to return.2

In addition to commemorating the student protestors, Carrington's painting pays homage to those who supported and saved some of the wounded students, notably Dr Fernando Ortiz Monasterio (1923-2012), to whom the painting is dedicated. Monasterio's 'operation' was radically different to Díaz Ordaz's oppressive regime, of course. He is presented as a medical and humanitarian shaman. He dominates the composition in his tall slender form as the healer at a time of military terror, or an intermediary between a violent moment in history and a better future. Fernando Ortiz Monasterio was a surgeon and teacher who specialized in cranio-facial surgery, assisting many children born with facial abnormalities or suffering tumours. He worked for the Ministry of Health in Mexico and was affiliated with the Graduate Division of UNAM as well as the Hospital General Gea Gonzalez, in the Tlalpan district. Monasterio was known for his interest in music, literature, anthropology and sociology, and for his determination to understanding how and why so many Mexican children were born with cranial deformations.3

Carrington's choice of medium for this work also pays homage to the humanism and skill of the doctor. She uses egg tempera, a technique which involves an emulsion of pigment and a water soluble binder – here the binder is egg yolk. Whilst a difficult process, prone to dry flaking, tempera had great symbolic significance in bringing art and science, the feminine (symbolised by the egg) and the masculine (the technical skill), together. Tempera and temperament share a common Latin root - temperare, to mix - and both involve the binding of things whether humors and tempers or pigments. In being associated with the feminine, her choice of tempera technique also serves as a striking counterpoint to the mechanical violence of the massacre. Tempera speaks to an old, life-giving process through the alchemical symbolism of the egg and by extension may be read as a means to challenge an emphatically modern, masculinist, political regime. Tempera was a popular medium in Surrealist circles, especially for women painters, and once Carrington moved to Mexico in 1943 it became a staple technique in her studio there. One friend described her studio as a 'narrow little room in old Mexico, the most dream-saturated place I know here'.4

Carrington's recourse to diverse cultural symbols ensures the viewer is intrigued by her use of dramatic colour and detail alike and searches out the stories behind them. We find English and Spanish text in the foreground, some of it in mirror writing; a palette dominated by bands of white and black - the doctor and his assistant are in white which symbolises light, and the androgynous patient they assist is dressed in a black cloak, the colour of which symbolises darkness and mourning. The colour red links further details, notably the patient's Cyclopean red eye and the dove's blood, which the small skeleton uses as ink. Here Carrington evokes traditional Christian symbolism as the skeleton traditionally denotes the inevitability of death, as in a memento mori. The diminutive size of the skeleton may also suggest children - those killed and wounded in the massacre, those assisted by the doctor, and the child who embodies the future of Mexico. The specificity of the historical moment is marked by the words of healing on the book the skeleton holds: 'WE HANGED / OUR HARPS / CARRIED / US'. Fittingly, the words refer to a communal lament and yearning for Jerusalem as well as a hatred for those that would destroy it - 'we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof'.5 Carrington's reference to these words suggests that the time for music has gone, instruments have been put away, and only the sound of mourning remains. The foot of the black cloaked figure in her painting reinforces this message in drawing the viewer's eye to multiple white crosses, denoting victims, as well as the red script in backward, mirror writing, which reads 'Thou hearest not, and in the night season, am not silent, Oh, my God, I cry'.6

But all is not lost, even if faith is challenged, merriment suspended and a rebellion cruelly halted. Carrington brings a ray of hope into the scene: red links the all-seeing eye of the patient and the blood of the bird and the biblical words, while in alchemical terms, red denotes sulphur or the final stage in the alchemical process as a base metal like lead (black, nigredo) turns through silver (white, albedo) to gold (red, rubedo), connoting success or rebirth. Carrington frequently fused references to European occultism (Spiritualism, Tarot, Tibetan Buddhism) with Mexican tradition (shamanism, rituals involving peyote or love potions, and the Mayan creation myth as articulated in the sixteenth-century text Popol Vuh). She magnifies the import of the massacre at Tlatelolco and its commemoration through further details which draw on Mayan culture: the blue rose symbolising sacrifice, the blue butterfly symbolising the spirit of deceased warriors, and the golden apple symbolising immortality.

The ghostly figure of a hummingbird above the doctor further alludes to the Mayans, for whom the bird was sacred and had healing...