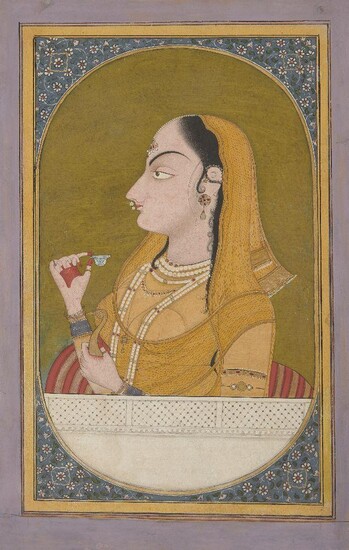

Lady holding a Wine Cup, by a Pahari artist working in the Garhwal style, 1780-1800, opaque watercolours heightened with gold on paper, 29.8 x 18.6cm. A heavily bejewelled lady is seated at a white marble balcony holding a blue-and-white porcelain...

Lady holding a Wine Cup, by a Pahari artist working in the Garhwal style, 1780-1800, opaque watercolours heightened with gold on paper, 29.8 x 18.6cm. A heavily bejewelled lady is seated at a white marble balcony holding a blue-and-white porcelain wine cup in her hennaed hand. She holds in her other hand a gold flask or rosewater sprinkler, cast in the form of a bird with the sinuous, elongated neck of a crane. These symbols, together with the window and balcony at which she appears, tell us that she is a courtesan. As no respectable woman would allow herself to be painted by a male artist, portraits of women in Indian paintings are invariably either idealised representations of unavailable princesses, or courtesans who are often depicted holding a flask or a wine cup, iconographic symbols that tell us the lady in question is available. Henna was used to decorate the hands of young women before marriage, an additional reference to her function. The window portrait format was often used for courtesans, perhaps by this form of display suggesting that they are “public” women, but also subtly subverting the convention of the jharokha windows used for the depiction of India’s emperors and princes. Another common symbol in such paintings is a bird, especially in the Deccan. Sometimes it is a nightingale, as in a late 17th century Golconda portrait of a courtesan in the Binney collection in San Diego (Desai, no. 61; Zebrowski, no. 179), in which the bird perched on the lady’s hand suggests that she is a akin to the rose in the traditional rose-and-nightingale motif of Persian love poetry and paintings (gul-o-bulbul). Sometimes it is a parrot or parakeet as in other Golconda paintings from the late 17th century (Falk and Archer, no. 478; Topsfield, no. 142). The avian imagery of these paintings seems to refer to the communicative capacities of such birds, pouring sweet nothings into the ear of the beloved. In the north, the favoured imagery is that of the flask and/or the wine cup, suggestive of the pleasures of intoxication whether real or in the transports of love. Such images are too numerous to refer to here, but for a particularly fine Mughal example see Losty 2008, no. 114 and references. Our artist here seems to have combined the two images by converting his wine flask into a bird. Pictures within flattened oval frames are usually associated with Kangra and related schools at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries. Though undoubtedly from the Pahari region, the courtesan has a hauteur and sophistication quite different from the sweetness of the female figures seen in paintings from Kangra itself. Our painting has something of the harder line seen at Garhwal. Particularly noticeable is her profile with very high forehead, large nose and diminutive mouth which together with the high arch of the eyebrow are found in the Garhwal school of the late 18th century (Archer, Garhwal 3-5).

[ translate ]View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Reserve

Time, Location

Auction House

Lady holding a Wine Cup, by a Pahari artist working in the Garhwal style, 1780-1800, opaque watercolours heightened with gold on paper, 29.8 x 18.6cm. A heavily bejewelled lady is seated at a white marble balcony holding a blue-and-white porcelain wine cup in her hennaed hand. She holds in her other hand a gold flask or rosewater sprinkler, cast in the form of a bird with the sinuous, elongated neck of a crane. These symbols, together with the window and balcony at which she appears, tell us that she is a courtesan. As no respectable woman would allow herself to be painted by a male artist, portraits of women in Indian paintings are invariably either idealised representations of unavailable princesses, or courtesans who are often depicted holding a flask or a wine cup, iconographic symbols that tell us the lady in question is available. Henna was used to decorate the hands of young women before marriage, an additional reference to her function. The window portrait format was often used for courtesans, perhaps by this form of display suggesting that they are “public” women, but also subtly subverting the convention of the jharokha windows used for the depiction of India’s emperors and princes. Another common symbol in such paintings is a bird, especially in the Deccan. Sometimes it is a nightingale, as in a late 17th century Golconda portrait of a courtesan in the Binney collection in San Diego (Desai, no. 61; Zebrowski, no. 179), in which the bird perched on the lady’s hand suggests that she is a akin to the rose in the traditional rose-and-nightingale motif of Persian love poetry and paintings (gul-o-bulbul). Sometimes it is a parrot or parakeet as in other Golconda paintings from the late 17th century (Falk and Archer, no. 478; Topsfield, no. 142). The avian imagery of these paintings seems to refer to the communicative capacities of such birds, pouring sweet nothings into the ear of the beloved. In the north, the favoured imagery is that of the flask and/or the wine cup, suggestive of the pleasures of intoxication whether real or in the transports of love. Such images are too numerous to refer to here, but for a particularly fine Mughal example see Losty 2008, no. 114 and references. Our artist here seems to have combined the two images by converting his wine flask into a bird. Pictures within flattened oval frames are usually associated with Kangra and related schools at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries. Though undoubtedly from the Pahari region, the courtesan has a hauteur and sophistication quite different from the sweetness of the female figures seen in paintings from Kangra itself. Our painting has something of the harder line seen at Garhwal. Particularly noticeable is her profile with very high forehead, large nose and diminutive mouth which together with the high arch of the eyebrow are found in the Garhwal school of the late 18th century (Archer, Garhwal 3-5).

[ translate ]