PACIOLI, Luca (Lucas de Burgo S. Sepulchri; c.1445-1517). Somma di arithmetica, geometria, proporzioni e proporzionalità. Venice: Paganinus de Paganinis, 10-20 November 1494.

PACIOLI, Luca (Lucas de Burgo S. Sepulchri; c.1445-1517). Somma di arithmetica, geometria, proporzioni e proporzionalità. Venice: Paganinus de Paganinis, 10-20 November 1494.

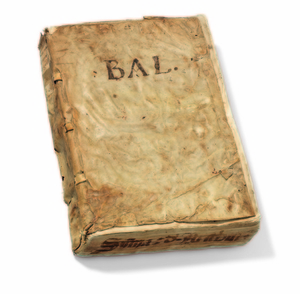

First edition of Luca Pacioli’s Somma di arithmetica, a book which has profoundly shaped our modern economic world. This copy in strictly original condition.

+ The most important mathematical book of the Renaissance, of direct influence on Leonardo da Vinci

+ The birth of modern business: being the first published description and enthusiastic endorsement of double-entry bookkeeping, the Venetian mercantile practice which still underpins global trade

+ A milestone in technology and computing, containing the first appearances in print of:

*mathematical statements using symbols for plus and minus

*the name and many of the ideas of Fibonacci, the 13th-century mathematician who introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals to Europe

+ The first popular mathematical book: published in the vernacular and intended for use by the professional classes

+ Very rare on the market: the present copy is the only one in original binding, and one of only three complete copies, recorded at auction in over fifty years

LEONARDO’S MATHEMATICIAN

Luca Pacioli’s life and career perfectly positioned him as the creator of the Renaissance’s most important mathematics book: he was a teacher, traveler, scholar, and—most importantly—a friend and collaborator of the most respected artistic and scholarly luminaries of the period. Born in Sansepolcro around 1445, Pacioli came of age within the sphere of influence of Florence’s humanism. He was raised by a local merchant family, where he would have been trained in basic trade arithmetic. Sansepolcro was also the birthplace and home of the great painter and mathematician Piero della Francesca. Piero mentored Pacioli, depicting his young friend in two paintings; in turn, the Somma includes Piero’s uncredited work on perspective and other topics—a fact which Vasari censures in his Lives of the Artists.

While still a youth, Pacioli traveled to Venice to tutor the sons of a local merchant in abbaco: the day-to-day mathematics used by the city’s businessmen and traders. This may have been where he first encountered double-entry bookkeeping. His next stop was Rome, where he became a friend and confidant of the great humanist polymath Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti was at the time a Papal secretary and connected Pacioli to the Catholic hierarchy in that city. The young math tutor began to study theology, eventually becoming a Franciscan friar. Alberti must have been a powerful mentor to the young Pacioli—an accomplished Renaissance thinker, but also, like Pacioli, not of high birth. While Alberti’s achievements were across diverse fields, from architecture to cryptography, it was mathematics that was central to how he understood the world—a view he clearly transmitted to Pacioli. In the dedication of the Somma, he writes that “nothing in creation will be found constituted but as number, weight, and measure.” After Alberti’s death in 1472, Pacioli left Rome to begin a career as a teacher, lecturing at universities in Perugia, Pisa, and Bologna.

In the 1490s, Pacioli returned to the town of his birth. He spent his time finishing his long-awaited book: a treatise containing all the math there was to know. His style and scope were informed by a didactic method honed from decades of teaching young boys, his direct observation of merchant practices, and his intimacy with some of the most brilliant minds (and important manuscripts) of his age. That book was the Somma, completed under the patronage of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, whose excellent library was an important resource and to whom the book is dedicated. Its publication earned Pacioli fame—and also the attention of another luminary of the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci.

Two years after its publication, Pacioli was invited to the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan, where Leonardo was working as an engineer. The two men became fast friends, living together and working on unraveling the further secrets of both linear perspective and divine geometry—the fruits of which can be seen in Leonardo’s paintings from the period, including the Last Supper, and the book they worked on together: Divina proportione, printed in 1509. Leonardo had been teaching himself techniques from Pacioli’s Somma—an education which continued during their intimacy in Milan. A to-do list in Leonardo’s Codex Atlanticus reads: “Learn the multiplication of roots from Maestro Luca” (331r), and both the Madrid and Forster codices contain notes on the Somma—in particular, sections on proportions and proportionality, including a mirror-version of the arbor proportionis et proportionalitatis on folio 82r of Pacioli’s work.

The famous portrait of Pacioli by Jacopo de' Barbari, painted in the wake of the acclaim earned from the Somma, was once thought to be by Leonardo. It portrays Luca Pacioli as a master of all the realms of mathematics—the Platonic mysteries of geometry alongside the everyday calculations of arithmetic, and both as a teacher (the figure in the background may be Guidobaldo or a nameless student) and a writer. His ability to unite all of these realms and communicate them to the public has earned him a place as a founding father of modern mathematics and technology.

A FOUNDATIONAL TEXT OF CAPITALISM

Pacioli, who began his career as an abbaco teacher and private tutor, was intimately familiar with the practical world of accounting, ledger books, and economic arithmetic. His Somma di arithmetica not only brought these ideas into print—some for the very first time—but elevated the concerns of the businessman and the practical accountant to the intellectual level of the rest of the humanist curriculum, presented as part of the sum of mathematical learning and an essential part of human knowledge. He confirms the study of economics as a liberal art.

Although double-entry bookkeeping had been known in Italy since at least the 13th century, Pacioli provides its first description in print in any language in book 9 of the Somma, entitled Particularis de computis et scripturis (“Details of Accounting and Recording”). In addition to eschewing the Latin of the scholastics in favor of the Italian of the merchants, Pacioli provides a remarkably clear and concise guide to succeeding in business. In outlining how to maintain account books, he gives examples and templates with easy-to-remember adages and even quotations from Dante.

The description of the “Venetian Method,” comprising book 9 of the Somma di arithmetica, is emblematic of a sea-change that had been developing in the status of mercantile theory and practice in Italy, where a middle class who worked for wages was growing in the cities. For several centuries loans had been forbidden as usury and merchants were generally looked down upon as exploiting the rich and the poor alike. But in the great trading centers of Italy, a new form of “business ethics” was being developed. Scholastic writers like San Bernardino of Siena and Antoninus Florentinus began to articulate a moral philosophy which made room for the practice of ethical trade and banking, for which the monetary landscape of the 15th century was increasingly calling.

The accuracy of account-keeping was a major tenet of these new systems of ethics. As economic historian Jacob Soll notes, “businessmen maintained republics,” and the integrity of account books was vital to the integrity of the businessman (and the state). While the proto-economic theorists of the scholastic universities had begun to address the morality of businessmen, they did not pursue practical questions of how this might be achieved. Pacioli’s work is a major advance in reconciling business with ethics, providing a clear guide to virtuous, as well as effective, accounting and pursuit of profit.

HOW TO SUCCEED IN BUSINESS

For the mathematical Pacioli, the well-kept account book maintains and preserves the health of the state. He writes that there are three necessities for a successful business:

*Cash or credit

*A good accountant

*Good internal control [“bello ordine”]

The accountant—who must be well-versed in mathematics—is responsible for the internal control of the books. If followed, Pacioli’s system allows for a business man to “pursue profit lawfully” and achieve good results. He also notes that “without double entry, businessmen would not sleep easily at night. Their minds would keep them awake with worry about their business. To prevent this stress, I wrote book 9 of the Somma” (trans. Cripps).

Pacioli details not only the mathematics of accounting, but the practical issues of how many and what kinds of ledgers to use, so that a business owner can understand exactly what they have and what they need to succeed. He writes: “begin with the assumption that a businessman has a goal when he goes into business. That goal he pursues enthusiastically. That goal, and the goal of every businessman who intends to be successful, is to make a lawful and reasonable profit.” The Somma emphasizes practices which are still basic to accounting: the importance of understanding inventory maintenance, cash versus capital, and using a uniform currency to keep accounts. Pacioli is also credited as the first author to describe the “rule of 72”—a method of calculating compound interest which continues to be part of the accounting curriculum today.

This view of business—underwritten by double-entry bookkeeping—was so successful that it has established itself in the language of vice and virtue writ large. While the Good Book may be scripture, God’s book is surely a ledger. During the Reformation, we begin to see the adoption of bookkeeping metaphors into the language of Heaven and Hell, where Heavenly credits and debits are weighed against each other in a final reckoning. David Wootton writes that “The account book was thus...

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

PACIOLI, Luca (Lucas de Burgo S. Sepulchri; c.1445-1517). Somma di arithmetica, geometria, proporzioni e proporzionalità. Venice: Paganinus de Paganinis, 10-20 November 1494.

First edition of Luca Pacioli’s Somma di arithmetica, a book which has profoundly shaped our modern economic world. This copy in strictly original condition.

+ The most important mathematical book of the Renaissance, of direct influence on Leonardo da Vinci

+ The birth of modern business: being the first published description and enthusiastic endorsement of double-entry bookkeeping, the Venetian mercantile practice which still underpins global trade

+ A milestone in technology and computing, containing the first appearances in print of:

*mathematical statements using symbols for plus and minus

*the name and many of the ideas of Fibonacci, the 13th-century mathematician who introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals to Europe

+ The first popular mathematical book: published in the vernacular and intended for use by the professional classes

+ Very rare on the market: the present copy is the only one in original binding, and one of only three complete copies, recorded at auction in over fifty years

LEONARDO’S MATHEMATICIAN

Luca Pacioli’s life and career perfectly positioned him as the creator of the Renaissance’s most important mathematics book: he was a teacher, traveler, scholar, and—most importantly—a friend and collaborator of the most respected artistic and scholarly luminaries of the period. Born in Sansepolcro around 1445, Pacioli came of age within the sphere of influence of Florence’s humanism. He was raised by a local merchant family, where he would have been trained in basic trade arithmetic. Sansepolcro was also the birthplace and home of the great painter and mathematician Piero della Francesca. Piero mentored Pacioli, depicting his young friend in two paintings; in turn, the Somma includes Piero’s uncredited work on perspective and other topics—a fact which Vasari censures in his Lives of the Artists.

While still a youth, Pacioli traveled to Venice to tutor the sons of a local merchant in abbaco: the day-to-day mathematics used by the city’s businessmen and traders. This may have been where he first encountered double-entry bookkeeping. His next stop was Rome, where he became a friend and confidant of the great humanist polymath Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti was at the time a Papal secretary and connected Pacioli to the Catholic hierarchy in that city. The young math tutor began to study theology, eventually becoming a Franciscan friar. Alberti must have been a powerful mentor to the young Pacioli—an accomplished Renaissance thinker, but also, like Pacioli, not of high birth. While Alberti’s achievements were across diverse fields, from architecture to cryptography, it was mathematics that was central to how he understood the world—a view he clearly transmitted to Pacioli. In the dedication of the Somma, he writes that “nothing in creation will be found constituted but as number, weight, and measure.” After Alberti’s death in 1472, Pacioli left Rome to begin a career as a teacher, lecturing at universities in Perugia, Pisa, and Bologna.

In the 1490s, Pacioli returned to the town of his birth. He spent his time finishing his long-awaited book: a treatise containing all the math there was to know. His style and scope were informed by a didactic method honed from decades of teaching young boys, his direct observation of merchant practices, and his intimacy with some of the most brilliant minds (and important manuscripts) of his age. That book was the Somma, completed under the patronage of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, whose excellent library was an important resource and to whom the book is dedicated. Its publication earned Pacioli fame—and also the attention of another luminary of the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci.

Two years after its publication, Pacioli was invited to the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan, where Leonardo was working as an engineer. The two men became fast friends, living together and working on unraveling the further secrets of both linear perspective and divine geometry—the fruits of which can be seen in Leonardo’s paintings from the period, including the Last Supper, and the book they worked on together: Divina proportione, printed in 1509. Leonardo had been teaching himself techniques from Pacioli’s Somma—an education which continued during their intimacy in Milan. A to-do list in Leonardo’s Codex Atlanticus reads: “Learn the multiplication of roots from Maestro Luca” (331r), and both the Madrid and Forster codices contain notes on the Somma—in particular, sections on proportions and proportionality, including a mirror-version of the arbor proportionis et proportionalitatis on folio 82r of Pacioli’s work.

The famous portrait of Pacioli by Jacopo de' Barbari, painted in the wake of the acclaim earned from the Somma, was once thought to be by Leonardo. It portrays Luca Pacioli as a master of all the realms of mathematics—the Platonic mysteries of geometry alongside the everyday calculations of arithmetic, and both as a teacher (the figure in the background may be Guidobaldo or a nameless student) and a writer. His ability to unite all of these realms and communicate them to the public has earned him a place as a founding father of modern mathematics and technology.

A FOUNDATIONAL TEXT OF CAPITALISM

Pacioli, who began his career as an abbaco teacher and private tutor, was intimately familiar with the practical world of accounting, ledger books, and economic arithmetic. His Somma di arithmetica not only brought these ideas into print—some for the very first time—but elevated the concerns of the businessman and the practical accountant to the intellectual level of the rest of the humanist curriculum, presented as part of the sum of mathematical learning and an essential part of human knowledge. He confirms the study of economics as a liberal art.

Although double-entry bookkeeping had been known in Italy since at least the 13th century, Pacioli provides its first description in print in any language in book 9 of the Somma, entitled Particularis de computis et scripturis (“Details of Accounting and Recording”). In addition to eschewing the Latin of the scholastics in favor of the Italian of the merchants, Pacioli provides a remarkably clear and concise guide to succeeding in business. In outlining how to maintain account books, he gives examples and templates with easy-to-remember adages and even quotations from Dante.

The description of the “Venetian Method,” comprising book 9 of the Somma di arithmetica, is emblematic of a sea-change that had been developing in the status of mercantile theory and practice in Italy, where a middle class who worked for wages was growing in the cities. For several centuries loans had been forbidden as usury and merchants were generally looked down upon as exploiting the rich and the poor alike. But in the great trading centers of Italy, a new form of “business ethics” was being developed. Scholastic writers like San Bernardino of Siena and Antoninus Florentinus began to articulate a moral philosophy which made room for the practice of ethical trade and banking, for which the monetary landscape of the 15th century was increasingly calling.

The accuracy of account-keeping was a major tenet of these new systems of ethics. As economic historian Jacob Soll notes, “businessmen maintained republics,” and the integrity of account books was vital to the integrity of the businessman (and the state). While the proto-economic theorists of the scholastic universities had begun to address the morality of businessmen, they did not pursue practical questions of how this might be achieved. Pacioli’s work is a major advance in reconciling business with ethics, providing a clear guide to virtuous, as well as effective, accounting and pursuit of profit.

HOW TO SUCCEED IN BUSINESS

For the mathematical Pacioli, the well-kept account book maintains and preserves the health of the state. He writes that there are three necessities for a successful business:

*Cash or credit

*A good accountant

*Good internal control [“bello ordine”]

The accountant—who must be well-versed in mathematics—is responsible for the internal control of the books. If followed, Pacioli’s system allows for a business man to “pursue profit lawfully” and achieve good results. He also notes that “without double entry, businessmen would not sleep easily at night. Their minds would keep them awake with worry about their business. To prevent this stress, I wrote book 9 of the Somma” (trans. Cripps).

Pacioli details not only the mathematics of accounting, but the practical issues of how many and what kinds of ledgers to use, so that a business owner can understand exactly what they have and what they need to succeed. He writes: “begin with the assumption that a businessman has a goal when he goes into business. That goal he pursues enthusiastically. That goal, and the goal of every businessman who intends to be successful, is to make a lawful and reasonable profit.” The Somma emphasizes practices which are still basic to accounting: the importance of understanding inventory maintenance, cash versus capital, and using a uniform currency to keep accounts. Pacioli is also credited as the first author to describe the “rule of 72”—a method of calculating compound interest which continues to be part of the accounting curriculum today.

This view of business—underwritten by double-entry bookkeeping—was so successful that it has established itself in the language of vice and virtue writ large. While the Good Book may be scripture, God’s book is surely a ledger. During the Reformation, we begin to see the adoption of bookkeeping metaphors into the language of Heaven and Hell, where Heavenly credits and debits are weighed against each other in a final reckoning. David Wootton writes that “The account book was thus...