Paul Gauguin

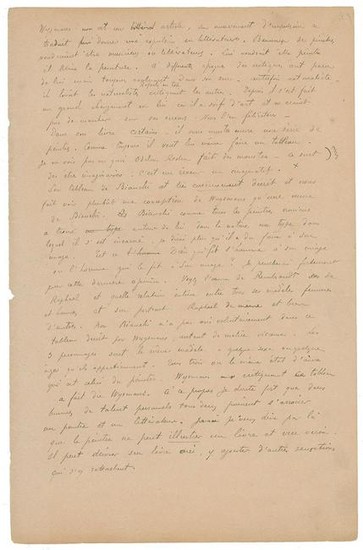

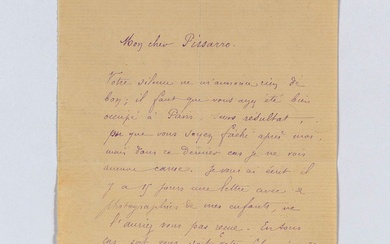

Important French post-Impressionist painter (1848–1903) recognized for his experimental use of color and synthetist style. In 1891, he traveled to Tahiti, where the brilliant hues and primitive sculpture closely complemented his own art, which was marked by strong colors, few lines, and flat patterns. Unsigned handwritten manuscript in French by Paul Gauguin, two pages both sides, 8 x 12.25, no date. Gauguin muses on contemporary art, highlighted by a lengthy discussion of his contemporary, Odilon Redon. He also references numerous artists including Rembrandt, Raphael, Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavanne, and Bianchi, as well as novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans.

In part (translated): "Huysmans is an artist. The impetus that moves him takes the form of producing an expulsion into literature. Many painters would like to be musicians or men of letters. He would like to be a painter; he illuminates painting. Critiques by him have appeared at different times, but always developing in his direction. Once a naturalist, he used to praise the naturalists, Raffaeli at their head, and criticize the others. Afterward, a great change took place in him, because he thirsts for art and is not afraid of going back over his mistakes. We congratulate him for it.

In his book Certains [Certain ones], he once again shows us a series of painters. As always, he wants to create a picture himself.

I don’t see how Odilon Redon creates monsters; they’re imaginary beings. He’s a dreamer, a man of imagination.

His Bianchi picture is very curiously described and shows us a conception by Huysmans more than a work by Bianchi. Bianchi, like all the old painters, found around him in nature a type in which he became incarnated, or rather, I would say, which he must have made in his image. Is it God who makes man in his image, or man who makes him in his image? I would come down strongly on the side of the latter opinion. Look at the work of Rembrandt, of Raphael, and what an intimate relationship there is between all his models, men and women, and his portrait. The same is true of Raphael and a good number of others. No, Bianchi did not voluntarily put so much vicious malice into the picture Huysmans describes. The three figures are the same model, whatever their sex or age. All three are in the same spiritual state, which is that of the painter. Huysmans in critiquing that picture did a Huysmans. In that connection, I doubt very much that two talented men, both of them egoistical, a painter and a man of letters, can be partners. I would never want to say by this that a painter cannot illustrate a book and vice versa. He can decorate his book, yes, and add other sensations that are associated with it.

On ugliness. A burning question and one that is the touchstone of our modern art and of criticism of it.

We are going to try, not to resolve it, but to shed some light on it that can give us a glimpse of it, if possible.

On a thorough examination of Redon’s profound art, we find little trace of the monstrous, no more than of statues and of Notre-Dame. Certainly, some animals that we don’t see, even the antediluvian ones, have the appearance of monsters due to that tendency that we have to only recognize as true and normal what is habitually in the majority. Nature has mysterious infinities and a power of imagination that are such that she shows them her desire for creation by always varying her productions. The artist himself is one of her means of creation, and for me, Odilon Redon is one of those she has chosen for that continuation of creation. Dreams become reality in him through the verisimilitude that he gives them. All his plants, embryonic beings, are essentially human. They have surely lived with us; they have their share of suffering.

Amid a black atmosphere, we finally perceive one, two tree trunks, and one of them is topped by something resembling a man’s head. With an extreme logic, he leaves us in doubt about that being. Is it truly a man, or rather a vague resemblance? Whatever the case may be, both of them live inseparably on that page, both enduring the same storms.

And that shaggy-haired head of a man, with a skull split open and a smaller eye in the opening: is it a monster? No! In the silence of the night and the darkness, our eye sees, our ear hears, but all this perhaps happens in memory, before our inner tribunal.

Et oculos habent et non vident. What exact sense is to be attributed to that phrase? Was it indeed matter that Jesus had in mind in making use of matter, the eye?

Likewise, Redon, who speaks with his pencil: is it indeed matter that he has in mind with that inner eye? In all his work, I see only a language of the heart, one that is quite human and not monstrous. What does the means of expression matter? An impetus from the heart.

In contrast to that critique, Huysmans speaks about Gustave Moreau with very great esteem. Fine, we esteem him also, but to what degree? What’s there is a spirit that is essentially not very literary but desires to be. Thus Gustave Moreau speaks only a language already written by men of letters; it’s a kind of illustration of old stories. The impetus that moves him is quite far from the heart; thus he loves the richness of material things. He is utterly in the wrong. He makes out of every human being a jewel covered with jewels. (The soul is missing.) You cool the lava of a volcano and make a stone from boiling blood. Even if it was a ruby, throw it far from you. But rubies are wanted and are sold to diamond dealers! In sum, Gustave Moreau is a fine chiseler.

Impetus in Huysmans

On the other hand, Puvis de Chavannes does not smile at you. The impetuses that move him do not smile at you. Simplicity, nobility no longer suit the age. What do you want, eminent art critic? Those people will one day belong to their age. If it does not happen on our planet, it will happen on another more favorable to beautiful things. And nevertheless, I do not want to believe that our [...]

Redon] Eye: examination of conscience. Double-edged, like a temple to that examination in the style of Buddha, always a small figure alone in meditation, surrounded by palms or leaves that filter a silent twilight. There, certainly, you have the eternal spiritual state that will not be transformed again: nirvana.

Fattening of the imagination / Tapestry

——————

Male. Sea coconut. Coconut in two parts that open like the female genitalia, from which arises an enormous phallus that embeds itself in the earth to germinate. The inhabitants long considered it the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

——————

Aden. Solomon’s well or cisterns." In fine condition. It is noteworthy that Gauguin mentions a sculpture of a 'sea coconut,' or 'coco de mer,' as he produced such a carving in the early 1900s which now resides in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. A significant artistic manuscript from the important painter.

Format:Handwritten Manuscript

View it on

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Important French post-Impressionist painter (1848–1903) recognized for his experimental use of color and synthetist style. In 1891, he traveled to Tahiti, where the brilliant hues and primitive sculpture closely complemented his own art, which was marked by strong colors, few lines, and flat patterns. Unsigned handwritten manuscript in French by Paul Gauguin, two pages both sides, 8 x 12.25, no date. Gauguin muses on contemporary art, highlighted by a lengthy discussion of his contemporary, Odilon Redon. He also references numerous artists including Rembrandt, Raphael, Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavanne, and Bianchi, as well as novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans.

In part (translated): "Huysmans is an artist. The impetus that moves him takes the form of producing an expulsion into literature. Many painters would like to be musicians or men of letters. He would like to be a painter; he illuminates painting. Critiques by him have appeared at different times, but always developing in his direction. Once a naturalist, he used to praise the naturalists, Raffaeli at their head, and criticize the others. Afterward, a great change took place in him, because he thirsts for art and is not afraid of going back over his mistakes. We congratulate him for it.

In his book Certains [Certain ones], he once again shows us a series of painters. As always, he wants to create a picture himself.

I don’t see how Odilon Redon creates monsters; they’re imaginary beings. He’s a dreamer, a man of imagination.

His Bianchi picture is very curiously described and shows us a conception by Huysmans more than a work by Bianchi. Bianchi, like all the old painters, found around him in nature a type in which he became incarnated, or rather, I would say, which he must have made in his image. Is it God who makes man in his image, or man who makes him in his image? I would come down strongly on the side of the latter opinion. Look at the work of Rembrandt, of Raphael, and what an intimate relationship there is between all his models, men and women, and his portrait. The same is true of Raphael and a good number of others. No, Bianchi did not voluntarily put so much vicious malice into the picture Huysmans describes. The three figures are the same model, whatever their sex or age. All three are in the same spiritual state, which is that of the painter. Huysmans in critiquing that picture did a Huysmans. In that connection, I doubt very much that two talented men, both of them egoistical, a painter and a man of letters, can be partners. I would never want to say by this that a painter cannot illustrate a book and vice versa. He can decorate his book, yes, and add other sensations that are associated with it.

On ugliness. A burning question and one that is the touchstone of our modern art and of criticism of it.

We are going to try, not to resolve it, but to shed some light on it that can give us a glimpse of it, if possible.

On a thorough examination of Redon’s profound art, we find little trace of the monstrous, no more than of statues and of Notre-Dame. Certainly, some animals that we don’t see, even the antediluvian ones, have the appearance of monsters due to that tendency that we have to only recognize as true and normal what is habitually in the majority. Nature has mysterious infinities and a power of imagination that are such that she shows them her desire for creation by always varying her productions. The artist himself is one of her means of creation, and for me, Odilon Redon is one of those she has chosen for that continuation of creation. Dreams become reality in him through the verisimilitude that he gives them. All his plants, embryonic beings, are essentially human. They have surely lived with us; they have their share of suffering.

Amid a black atmosphere, we finally perceive one, two tree trunks, and one of them is topped by something resembling a man’s head. With an extreme logic, he leaves us in doubt about that being. Is it truly a man, or rather a vague resemblance? Whatever the case may be, both of them live inseparably on that page, both enduring the same storms.

And that shaggy-haired head of a man, with a skull split open and a smaller eye in the opening: is it a monster? No! In the silence of the night and the darkness, our eye sees, our ear hears, but all this perhaps happens in memory, before our inner tribunal.

Et oculos habent et non vident. What exact sense is to be attributed to that phrase? Was it indeed matter that Jesus had in mind in making use of matter, the eye?

Likewise, Redon, who speaks with his pencil: is it indeed matter that he has in mind with that inner eye? In all his work, I see only a language of the heart, one that is quite human and not monstrous. What does the means of expression matter? An impetus from the heart.

In contrast to that critique, Huysmans speaks about Gustave Moreau with very great esteem. Fine, we esteem him also, but to what degree? What’s there is a spirit that is essentially not very literary but desires to be. Thus Gustave Moreau speaks only a language already written by men of letters; it’s a kind of illustration of old stories. The impetus that moves him is quite far from the heart; thus he loves the richness of material things. He is utterly in the wrong. He makes out of every human being a jewel covered with jewels. (The soul is missing.) You cool the lava of a volcano and make a stone from boiling blood. Even if it was a ruby, throw it far from you. But rubies are wanted and are sold to diamond dealers! In sum, Gustave Moreau is a fine chiseler.

Impetus in Huysmans

On the other hand, Puvis de Chavannes does not smile at you. The impetuses that move him do not smile at you. Simplicity, nobility no longer suit the age. What do you want, eminent art critic? Those people will one day belong to their age. If it does not happen on our planet, it will happen on another more favorable to beautiful things. And nevertheless, I do not want to believe that our [...]

Redon] Eye: examination of conscience. Double-edged, like a temple to that examination in the style of Buddha, always a small figure alone in meditation, surrounded by palms or leaves that filter a silent twilight. There, certainly, you have the eternal spiritual state that will not be transformed again: nirvana.

Fattening of the imagination / Tapestry

——————

Male. Sea coconut. Coconut in two parts that open like the female genitalia, from which arises an enormous phallus that embeds itself in the earth to germinate. The inhabitants long considered it the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

——————

Aden. Solomon’s well or cisterns." In fine condition. It is noteworthy that Gauguin mentions a sculpture of a 'sea coconut,' or 'coco de mer,' as he produced such a carving in the early 1900s which now resides in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. A significant artistic manuscript from the important painter.

Format:Handwritten Manuscript