Real-life Bridgerton ? 2nd edition, 1807

[Lady Anne HAMILTON (1766-1846)].

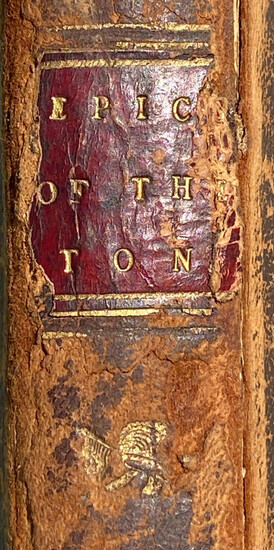

The Epics of the Ton; or, the glories of the great world: a poem, in two books, with notes and illustrations. The second edition, with considerable additions. London: printed by and for C. and R. Baldwin, 1807. Octavo (7 ½ x 4 ½ inches; 190 x 114mm). Pp. [i-]iv[-v-vi; 1-]4-190, ‘161’, 192-280 + 2pp publisher’s advertisements, numerous . (Some light spotting and toning). Contemporary sheep, the flat spine divided into six compartments by gilt rules, red morocco label in the second, the others with a simple repeat design of a centrally-place simple gilt 'trophy tool' featuring a hand-axe, a flag and a Phrygian cap (worn, covers attached but with joints split, spine damaged [see images]). Provenance: N. Macdonald Buchanan (inscription dated 1817 on front free endpaper).

Second edition describing the scandalous behavior of the ‘Ton’: a real-life parallel Bridgerton. Lady Anne Hamilton a real-life parallel Penelope Featherington. This work was “In part a defense of Caroline, Princess of Wales … and in part a gossipy satire on philandering Regency elites” (see below)

A talked-about best-seller with initials identifying the subjects: the ‘game’ of filling in the blanks took off and the book ran to three editions in the first year of publication.

Lady Anne Hamilton singles out 25 women and 17 men. In the present copy, there are contemporary penciled notes identifying 18 of the women, and 5 of the men. See the following pages (in the Female Book): 14, 18, 24, 28 (five individuals identified collectively as ‘daughters to the D. of Gordon’), 30, 34, 42, 55, 57, 60, 66, 68, 73, 105; (in the Male Book:) 166, 194, 211, 225, 270. The tooling to the spine perhaps echoes lady Anne Hamilton’s radical leanings: the Phrygian cap was, at the time, strongly identified with the French revolution.

‘Lady Anne Hamilton was born in 1766. She was the daughter of Archibald Hamilton, 9th Duke of Hamilton. She became a lady-in-waiting to Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales and estranged wife of the Prince Regent. She held this post until 1813 when the Princess went into voluntary exile in Italy. Lady Anne had radical sensibilities and on the Prince succeeding as George IV on 29 January 1820, repeatedly urged Caroline to return and claim her position as Queen Consort of Great Britain. She and radicals such as Henry Brougham and William Cobbett saw the Queen as a focus for the reformist Whig opposition. She crossed to France to meet Caroline at St. Omer, and with Alderman Matthew Wood, a radical former Lord Mayor of London, escorted her back to the capital. She resumed her position in Caroline's household, accompanying her to her trial for adultery in the House of Lords in August 1820, and remaining almost her sole supporter among ladies of consequence until her acquittal. When Caroline sought admittance to the Coronation in Westminster Abbey to take her rightful place beside George on 19 July 1821, Lady Anne Hamilton and Lady Hood were her two ladies-in-waiting. Being debarred and humiliated broke Caroline's spirit, and Hamilton was with her until her death on 7 August 1821 and her burial in Brunswick later that month.

Lady Anne was described by Creevey, at the trial, as "full six feet high and bears a striking resemblance to one of Lord Derby's great red deer"

Lady Anne Hamilton published a satirical epic poem called Epics of the Ton in 1807. The work, which was published anonymously, satirised the main figures involved in what was called "The Delicate Investigation" of the morality and suspected adultery of Caroline of Brunswick. Hamilton referred to the main characters by their initials.’ (wikipedia).

“Published anonymously, Hamilton’s Epics of the Ton decries gambling and illicit sex in London high society. In part a defense of Caroline, Princess of Wales, for whom Hamilton (1766–1846) was for a time a lady in waiting, and in part a gossipy satire on philandering Regency elites, Epics of the Ton exploits the media-driven clamor for celebrity scandal in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century England. The division into two gendered sections, titled the Male Book and the Female Book, makes Epics of the Ton unique among satires. The work ridicules seventeen men and twenty-five women, mainly aristocrat-politicians and society hostesses, who are identified in the Table of Contents and the section headers only by initials: D— of B—, V— C—, etc. Additional blanks throughout the poem and its footnotes invite readers to put names to the textual clues, in effect doing the work Hamilton begs of her muse: “From next year’s Lethe, and oblivion drear, / Come save the deeds” of the London beau monde. Reacting to the poem’s “lust [for] personal defamation,” the poet Anna Seward wrote that she wished Epics of the Ton would suffer a “total famine of readers.” Yet feast, not famine, better describes the poem’s brief, intense popularity, as it saw three editions, all in 1807, and perhaps would have enjoyed more had it not cost an expensive 7s. 6d. Excerpts were reprinted in papers as far away as Bombay (Mumbai). In later years, the title persisted as a popular byword for ugly gossip.

Hamilton—a Scot, the daughter of Archibald Hamilton, 9th Duke of Hamilton, and a partisan of Caroline during the Delicate Investigation of 1806, the official Parliamentary inquiry into Caroline’s fidelity to the Regent—moved in the same courtly circles that her poem attacked. Anonymity was crucial for elite women satirists, and it was not until the 1880s that the poem was attributed to Hamilton. That readers were apparently less interested in identifying the anonymous author than they were in attributing the scurrilous deeds the poem describes should not surprise us. Anonymous satire was so commonplace in 1807 as to be unremarkable, and the pull of the author function was weaker than usual in Epics of the Ton, which announced itself as a patchwork of public gossip rather than the original disclosures of a unique personality. No doubt anonymity helped Hamilton avoid social reprisal, even if most of the poem’s tawdry tidbits had already circulated widely in the press. That Hamilton attacks her own is also not surprising. As Catherine Keane observes, “satiric attack is a vehicle for marking out groups that are dangerously close to the satirist.” Perhaps Hamilton was disturbed by her proximity to the gambling and adultery she mocks. In any case, the poem’s criticism of the sexual infractions and domestic neglect of fashionable London women appears to be sincere enough.” (M. Edson. “Manuscript Notations and Cultural Memory” in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, Volume 50 (2020), pages 169–184).

View it on

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

[Lady Anne HAMILTON (1766-1846)].

The Epics of the Ton; or, the glories of the great world: a poem, in two books, with notes and illustrations. The second edition, with considerable additions. London: printed by and for C. and R. Baldwin, 1807. Octavo (7 ½ x 4 ½ inches; 190 x 114mm). Pp. [i-]iv[-v-vi; 1-]4-190, ‘161’, 192-280 + 2pp publisher’s advertisements, numerous . (Some light spotting and toning). Contemporary sheep, the flat spine divided into six compartments by gilt rules, red morocco label in the second, the others with a simple repeat design of a centrally-place simple gilt 'trophy tool' featuring a hand-axe, a flag and a Phrygian cap (worn, covers attached but with joints split, spine damaged [see images]). Provenance: N. Macdonald Buchanan (inscription dated 1817 on front free endpaper).

Second edition describing the scandalous behavior of the ‘Ton’: a real-life parallel Bridgerton. Lady Anne Hamilton a real-life parallel Penelope Featherington. This work was “In part a defense of Caroline, Princess of Wales … and in part a gossipy satire on philandering Regency elites” (see below)

A talked-about best-seller with initials identifying the subjects: the ‘game’ of filling in the blanks took off and the book ran to three editions in the first year of publication.

Lady Anne Hamilton singles out 25 women and 17 men. In the present copy, there are contemporary penciled notes identifying 18 of the women, and 5 of the men. See the following pages (in the Female Book): 14, 18, 24, 28 (five individuals identified collectively as ‘daughters to the D. of Gordon’), 30, 34, 42, 55, 57, 60, 66, 68, 73, 105; (in the Male Book:) 166, 194, 211, 225, 270. The tooling to the spine perhaps echoes lady Anne Hamilton’s radical leanings: the Phrygian cap was, at the time, strongly identified with the French revolution.

‘Lady Anne Hamilton was born in 1766. She was the daughter of Archibald Hamilton, 9th Duke of Hamilton. She became a lady-in-waiting to Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales and estranged wife of the Prince Regent. She held this post until 1813 when the Princess went into voluntary exile in Italy. Lady Anne had radical sensibilities and on the Prince succeeding as George IV on 29 January 1820, repeatedly urged Caroline to return and claim her position as Queen Consort of Great Britain. She and radicals such as Henry Brougham and William Cobbett saw the Queen as a focus for the reformist Whig opposition. She crossed to France to meet Caroline at St. Omer, and with Alderman Matthew Wood, a radical former Lord Mayor of London, escorted her back to the capital. She resumed her position in Caroline's household, accompanying her to her trial for adultery in the House of Lords in August 1820, and remaining almost her sole supporter among ladies of consequence until her acquittal. When Caroline sought admittance to the Coronation in Westminster Abbey to take her rightful place beside George on 19 July 1821, Lady Anne Hamilton and Lady Hood were her two ladies-in-waiting. Being debarred and humiliated broke Caroline's spirit, and Hamilton was with her until her death on 7 August 1821 and her burial in Brunswick later that month.

Lady Anne was described by Creevey, at the trial, as "full six feet high and bears a striking resemblance to one of Lord Derby's great red deer"

Lady Anne Hamilton published a satirical epic poem called Epics of the Ton in 1807. The work, which was published anonymously, satirised the main figures involved in what was called "The Delicate Investigation" of the morality and suspected adultery of Caroline of Brunswick. Hamilton referred to the main characters by their initials.’ (wikipedia).

“Published anonymously, Hamilton’s Epics of the Ton decries gambling and illicit sex in London high society. In part a defense of Caroline, Princess of Wales, for whom Hamilton (1766–1846) was for a time a lady in waiting, and in part a gossipy satire on philandering Regency elites, Epics of the Ton exploits the media-driven clamor for celebrity scandal in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century England. The division into two gendered sections, titled the Male Book and the Female Book, makes Epics of the Ton unique among satires. The work ridicules seventeen men and twenty-five women, mainly aristocrat-politicians and society hostesses, who are identified in the Table of Contents and the section headers only by initials: D— of B—, V— C—, etc. Additional blanks throughout the poem and its footnotes invite readers to put names to the textual clues, in effect doing the work Hamilton begs of her muse: “From next year’s Lethe, and oblivion drear, / Come save the deeds” of the London beau monde. Reacting to the poem’s “lust [for] personal defamation,” the poet Anna Seward wrote that she wished Epics of the Ton would suffer a “total famine of readers.” Yet feast, not famine, better describes the poem’s brief, intense popularity, as it saw three editions, all in 1807, and perhaps would have enjoyed more had it not cost an expensive 7s. 6d. Excerpts were reprinted in papers as far away as Bombay (Mumbai). In later years, the title persisted as a popular byword for ugly gossip.

Hamilton—a Scot, the daughter of Archibald Hamilton, 9th Duke of Hamilton, and a partisan of Caroline during the Delicate Investigation of 1806, the official Parliamentary inquiry into Caroline’s fidelity to the Regent—moved in the same courtly circles that her poem attacked. Anonymity was crucial for elite women satirists, and it was not until the 1880s that the poem was attributed to Hamilton. That readers were apparently less interested in identifying the anonymous author than they were in attributing the scurrilous deeds the poem describes should not surprise us. Anonymous satire was so commonplace in 1807 as to be unremarkable, and the pull of the author function was weaker than usual in Epics of the Ton, which announced itself as a patchwork of public gossip rather than the original disclosures of a unique personality. No doubt anonymity helped Hamilton avoid social reprisal, even if most of the poem’s tawdry tidbits had already circulated widely in the press. That Hamilton attacks her own is also not surprising. As Catherine Keane observes, “satiric attack is a vehicle for marking out groups that are dangerously close to the satirist.” Perhaps Hamilton was disturbed by her proximity to the gambling and adultery she mocks. In any case, the poem’s criticism of the sexual infractions and domestic neglect of fashionable London women appears to be sincere enough.” (M. Edson. “Manuscript Notations and Cultural Memory” in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, Volume 50 (2020), pages 169–184).