Untitled

PROPERTY FROM THE FAMILY COLLECTION OF NANDALAL BOSE

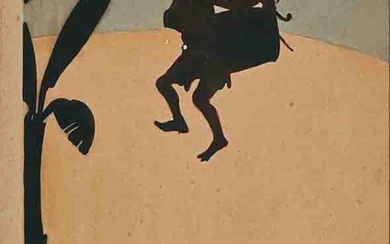

Ink on paper

9 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. (25 x 17.5 cm.)

Signed 'Rabindranath' lower centre

PROVENANCE:

From the collection of Nandalal Bose’s eldest daughter, Gouri Bhanja, née Bose, and thence by descent.

‘I am hopelessly entangled in the spell that the lines have cast around me.’

– Rabindranath Tagore

The Tagore family played a major role in what is known as the Bengal Renaissance, and Rabindranath Tagore is generally considered the most distinguished member of the family. His career as a poet, novelist, playwright and song- writer is well documented, and he became internationally famous when, in 1913, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. He was knighted by the King, and is held in the deepest esteem by his compatriots. Santiniketan, the school that he established on his family property, was modelled on the ancient forest schools of India, and by the 1920s, it had become an institution of world renown, with resident and visiting scholars from all over the globe. He was, furthermore, a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi, and an inspiration to the artists and scholars that he employed at Santiniketan, including Nandalal Bose. The Bose and Tagore families worked together on artistic projects, but they were also great friends. The intimacy of the relationship is reflected in the number of artworks that Rabindranath gifted to various members of Nandalal’s family, including this work, which was given to Gouri Bhanja (Nandalal’s eldest daughter).

For much of his life, despite a deep reverence for all the arts, Rabindranath focused on his writing. Although the majority of his paintings were produced in the last ten years of his life, he had sketched as a young man, and continued to draw intermittently throughout his life, gifting several of these early works to family and friends. Increasingly, however, towards the end of his life, he became more and more fascinated with painting. What began as doodling on his working manuscripts became an obsession, and in the last ten years of his life, he is known to have produced over a thousand works of art. He was the first Indian artist to exhibit his work across, Asia, Europe, and the United States.

Abanindranath Tagore says of his uncle’s work: ‘...it has happened like a volcanic eruption ... Just think of it – what an abundance of colour, lines and ideas was stored in the inmost recesses of the heart for which literature was not enough nor songs, nor lyrics – Which had to come out at last in paintings.’ (Abanindranath Tagore, reprinted, Bichitra, An Exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore’s Paintings, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, 2000, p. 33)

In 1920, Rabindranath Tagore requested Nandalal Bose to become the head of the Arts Faculty at Santiniketan, and they worked closely together until Tagore’s death in 1941. Nandalal himself, recognised that Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings represented some of the earliest examples of modernist art in India. He states, ‘Gurudev’s paintings may seem akin to primitive art because of their non- decorativeness and boldness of expression. But from the point of view of classification they are modern and alive with intelligence. The commitment to life which is the source of his artistic creativity is nourished by the culture, taste and thinking of our age; the touch or hint of primitivism has given it boldness and strength.’ (Nandalal Bose, ibid.)

Tagore’s artwork can be broadly categorised into three types: human figures, landscapes, and primitive animal forms that appear to be inspired by tribal and oceanic art. His first paintings were highly imaginative works, usually focused on animals or mythical creatures, and are full of vitality and humour. His human figures, are depicted with expressive gestures, often in theatrical settings. These were inspired by his experience of the theatre as a playwright, actor and director. In his portraits, produced during the 1930s, he rendered the human face in a way that remains reminiscent of a mask or persona. The current lot falls into this final category. ‘The human face is a constant in Tagore’s work, demonstrating his ongoing interest in human persona. As a writer, especially of short stories, he was used to linking human appearance with an inner human essence. Through his painting he found a similar opportunity in the representation of the human face. In the beginning, this usually led him to turn the face into a mask of a social type. Later, as his skills developed, shadows of faces he encountered began to meld with the painted faces and give them the resonance and expansiveness of characters.’ (‘Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Painter’, www.vam.ac.uk)

In the current work, we see a hooded figure in profile with a hooked nose and an open toothless mouth, that appears to have emerged from the same depths of Tagore’s sub- conscious as his fairy-tale figures in his short stories. The source of these characters often remains uncertain, but we know, that as a child, Tagore read both Bengali and Western fairly-tales, including a Bengali version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Rabindranath was also told Bengali folk tales by his father, and critics ascribe many of the characters in his short stories to his memories of these childhood tales. The sub-conscious doodling, that evolved later in his career into more elaborate figures and forms, was drawn from a deep well of literary characters and childhood fantasy, and the resulting forms, even to those unfamiliar with his writing, seem beguilingly familiar.

Throughout his work, Tagore reveals his natural tendency towards a symbolist approach. Both his sub-conscious doodles, and these more evolved works, seem to tap a universal archaic source. The artist states, ‘I have a force acting in me... that ever tries to win me for itself... this life impulse I speak of belongs to a personality beyond the ego.’ (‘RabindranathTagore’, Six IndianPainters, London, 1982, p. 18)

NATIONAL ART TREASURE – NON-EXPORTABLE ITEM

(Please refer to the Terms and Conditions of Sale at the back of the catalogue)

Condition: The colours and background tones of the original are slightly paler than the catalogue illustration, and the purple tones are slightly paler. Minor foxing visible around the head of the figure and several minor creases, partially visible in the catalogue illustration. Overall good condition.

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Reserve

Time, Location

Auction House

PROPERTY FROM THE FAMILY COLLECTION OF NANDALAL BOSE

Ink on paper

9 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. (25 x 17.5 cm.)

Signed 'Rabindranath' lower centre

PROVENANCE:

From the collection of Nandalal Bose’s eldest daughter, Gouri Bhanja, née Bose, and thence by descent.

‘I am hopelessly entangled in the spell that the lines have cast around me.’

– Rabindranath Tagore

The Tagore family played a major role in what is known as the Bengal Renaissance, and Rabindranath Tagore is generally considered the most distinguished member of the family. His career as a poet, novelist, playwright and song- writer is well documented, and he became internationally famous when, in 1913, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. He was knighted by the King, and is held in the deepest esteem by his compatriots. Santiniketan, the school that he established on his family property, was modelled on the ancient forest schools of India, and by the 1920s, it had become an institution of world renown, with resident and visiting scholars from all over the globe. He was, furthermore, a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi, and an inspiration to the artists and scholars that he employed at Santiniketan, including Nandalal Bose. The Bose and Tagore families worked together on artistic projects, but they were also great friends. The intimacy of the relationship is reflected in the number of artworks that Rabindranath gifted to various members of Nandalal’s family, including this work, which was given to Gouri Bhanja (Nandalal’s eldest daughter).

For much of his life, despite a deep reverence for all the arts, Rabindranath focused on his writing. Although the majority of his paintings were produced in the last ten years of his life, he had sketched as a young man, and continued to draw intermittently throughout his life, gifting several of these early works to family and friends. Increasingly, however, towards the end of his life, he became more and more fascinated with painting. What began as doodling on his working manuscripts became an obsession, and in the last ten years of his life, he is known to have produced over a thousand works of art. He was the first Indian artist to exhibit his work across, Asia, Europe, and the United States.

Abanindranath Tagore says of his uncle’s work: ‘...it has happened like a volcanic eruption ... Just think of it – what an abundance of colour, lines and ideas was stored in the inmost recesses of the heart for which literature was not enough nor songs, nor lyrics – Which had to come out at last in paintings.’ (Abanindranath Tagore, reprinted, Bichitra, An Exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore’s Paintings, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, 2000, p. 33)

In 1920, Rabindranath Tagore requested Nandalal Bose to become the head of the Arts Faculty at Santiniketan, and they worked closely together until Tagore’s death in 1941. Nandalal himself, recognised that Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings represented some of the earliest examples of modernist art in India. He states, ‘Gurudev’s paintings may seem akin to primitive art because of their non- decorativeness and boldness of expression. But from the point of view of classification they are modern and alive with intelligence. The commitment to life which is the source of his artistic creativity is nourished by the culture, taste and thinking of our age; the touch or hint of primitivism has given it boldness and strength.’ (Nandalal Bose, ibid.)

Tagore’s artwork can be broadly categorised into three types: human figures, landscapes, and primitive animal forms that appear to be inspired by tribal and oceanic art. His first paintings were highly imaginative works, usually focused on animals or mythical creatures, and are full of vitality and humour. His human figures, are depicted with expressive gestures, often in theatrical settings. These were inspired by his experience of the theatre as a playwright, actor and director. In his portraits, produced during the 1930s, he rendered the human face in a way that remains reminiscent of a mask or persona. The current lot falls into this final category. ‘The human face is a constant in Tagore’s work, demonstrating his ongoing interest in human persona. As a writer, especially of short stories, he was used to linking human appearance with an inner human essence. Through his painting he found a similar opportunity in the representation of the human face. In the beginning, this usually led him to turn the face into a mask of a social type. Later, as his skills developed, shadows of faces he encountered began to meld with the painted faces and give them the resonance and expansiveness of characters.’ (‘Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Painter’, www.vam.ac.uk)

In the current work, we see a hooded figure in profile with a hooked nose and an open toothless mouth, that appears to have emerged from the same depths of Tagore’s sub- conscious as his fairy-tale figures in his short stories. The source of these characters often remains uncertain, but we know, that as a child, Tagore read both Bengali and Western fairly-tales, including a Bengali version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Rabindranath was also told Bengali folk tales by his father, and critics ascribe many of the characters in his short stories to his memories of these childhood tales. The sub-conscious doodling, that evolved later in his career into more elaborate figures and forms, was drawn from a deep well of literary characters and childhood fantasy, and the resulting forms, even to those unfamiliar with his writing, seem beguilingly familiar.

Throughout his work, Tagore reveals his natural tendency towards a symbolist approach. Both his sub-conscious doodles, and these more evolved works, seem to tap a universal archaic source. The artist states, ‘I have a force acting in me... that ever tries to win me for itself... this life impulse I speak of belongs to a personality beyond the ego.’ (‘RabindranathTagore’, Six IndianPainters, London, 1982, p. 18)

NATIONAL ART TREASURE – NON-EXPORTABLE ITEM

(Please refer to the Terms and Conditions of Sale at the back of the catalogue)

Condition: The colours and background tones of the original are slightly paler than the catalogue illustration, and the purple tones are slightly paler. Minor foxing visible around the head of the figure and several minor creases, partially visible in the catalogue illustration. Overall good condition.