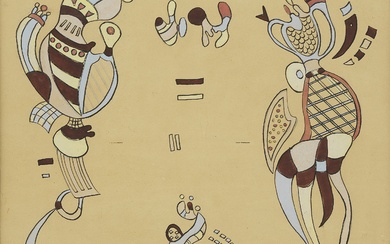

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Rigide et courbé

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)

Rigide et courbé

signed with monogram and dated '35' (lower left)

oil and sand on canvas

44 7/8 x 63 7/8 in. (114 x 162.4 cm.)

Executed in Paris, December 1935

Provenance

Solomon R. Guggenheim, New York (acquired from the artist, 1936).

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York (gift from the above, 1937); sale, Sotheby's & Co., London, 30 June 1964, lot 47.

Acquired at the above sale by the family of the present owner.

View Special Publication: Wassily Kandinsky?s Rigide et courbé

PROPERTY FROM AN IMPORTANT PRIVATE AMERICAN COLLECTION

The name of Wassily Kandinsky is instantly connected with the creation of abstract art and the compositional expression through brilliant color and non-objective forms. His invention of abstraction in the second decade of the 20th century resulted from a protracted search for ?pure painting? and it marked a decisive turning point in the development of modernism. It signified a revolutionary break with the established artistic values of Western art, dominant since the Renaissance, based on representation of nature and traditional perspective. Searching to free himself from these pictorial restrictions, and psychologically and philosophically dissatisfied with the prevalent theories of the 19th century positivism and materialism, Kandinsky aspired to find a new mode of visual expression that would introduce a spiritual element into art and life, while being compatible with and expressive of the new, contemporary world. Like his near contemporaries Kazimir Malevich in Russia and Piet Mondrian in Paris, also striving for the absolute in art, Kandinsky evolved his very personal and radical language of color, form and composition.

Kandinsky intended to enter an academic career having studied law, economics and ethnography at the University of Moscow. Yet, in 1896, at the rather late age of thirty, he made the momentous decision to become an artist and moved to Munich to study. Three unexpected experiences prompted that fortuitous decision. First, the discovery of a Claude Monet painting of a grainstack at the French Industrial and Art Exhibition in Moscow in 1896, in front of which he responded emotionally before even recognizing the subject of the picture. Second, the sight of one of his own paintings placed sideways on an easel created a strong emotional response, and at that moment Kandinsky realized that it was actually not necessary to recognize the subject in the composition. And third, his aesthetic impressions from an 1889 trip as an ethnographer for the Russian Imperial Society of Friends of Natural History, Anthropology and Ethnography which took him to the remote region of Vologda in northern Russia. The area was inhabited by the ancient Finno-Ugric Zyrian tribes, whose laws and customs Kandinsky travelled to study. It opened his eyes to the beauty of popular art, which surrounded him in the houses of the local people, which were decorated with brightly colored furniture and painted sculptural forms. Kandinsky then became aware of the impact of color and forms that created a tumultuous visual space and in turn this actively affected his perceptual and emotional experience. The recollection of this event remained with him throughout his creative life and stimulated his desire to arrive at a pictorial idiom which would offer the viewer the same sensation of finding himself ?within the picture,? surrounded by a riot of colors and abstract forms.

The artist?s path to abstraction was complex, marked by sequential periods of transition and experimentation, intellectual and pictorial shifts as well as creative diversity. He supplemented his changing pictorial language by extensive writings on art, contained in his two major treatises On the Spiritual in Art: And Painting in Particular, published in 1912, and Point and Line To Plane, published in 1926.

The summer of 1908 marked the moment of dramatic change in Kandinsky?s style, which was originally rooted in the dark manner of the Munich School. These early works were inflected by the influences of Post-Impressionism, and the widely popular idiom of Jugendstil. What contributed to his ?awakening? in 1908 were his trips not only through Russia but also to Holland and Italy, as well as North Africa. Each trip immersed Kandinsky in the force of color as a visual and emotional factor. It was at this time that he began writing a theory of colors. During his stay in France with his companion-painter Gabrielle Münter (in 1906 to 1907) Kandinsky had also discovered the brilliantly hued work of Henri Matisse and other Fauves, which further cemented his affinity for color as a principal compositional and structural element. Upon his return to Munich that emphasis on color became the driving force behind Kandinsky?s work. Initially, the striking colors defined recognizable imagery. Increasingly though, from late 1909, that recognizable imagery began to become more abstracted or veiled by employing thin, cursory lines and brush-strokes where color was no longer confined to form but effectively created form.

Another vital and far-reaching aspect of Kandinsky?s art theory and practice was his interest in music and the theories of synesthesia or cross-sensory metaphors and correspondences between color and sound or word and image. Kandinsky?s fascination with the emotional power of music informs the complexity of his art and his attitudes to musical and visual concepts of structure and harmony of the composition. In the conclusion to the On the Spiritual he assigns to his works titles such Impressions, Improvisations and Compositions, a clear and simple reference to music. In search of the new pictorial idiom adequate to what he called ?an Epoch of the Great Spiritual?. Kandinsky believed this new aesthetic ought to reflect both the internal and external elements: the internal meant emotions or ?vibrations? of the soul while the external meant the innovative visual form. That, according to Kandinsky?s vision, could only be achieved through a visual language not tied down to the forms of reality. Like music that speaks ?to the soul? through abstract means, the visual art should aspire to create means of expression parallel to those of music. Ever since he heard Wagner?s ?Lohengrin? at the Imperial Theatre in 1896, Kandinsky felt special attraction to Wagner, whose music was greatly admired by the Symbolists for its idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk that embraced word, music, and the visual arts. Moreover, French, Belgian, and Russian symbolist theories of synesthesia, dominant at the end of the 19th century, heightened Kandinsky?s interest in the affinities between painting and music. They drew upon the theory of correspondences already formulated in the mid-19th century by the critic, poet and writer Charles Baudelaire.

Additional sources of his inspiration were the color theories of Goethe and Hermann Helmholtz, as well as other contemporaneous European and Russian scientific and Theosophist teachings. Kandinsky was conversant with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, theosophist writings and teachings of Madame Helena Blavatsky, and lectures by Rudolf Steiner. He closely followed Russian theories of mysticism, particularly those of Soloview and Dmitri Merezhkovsky. Furthermore, the music of Arnold Schoenberg and his Theory of Harmony, as well as the principle of the ?emancipated dissonance,? emphasized Kandinsky?s affinity with musical language.

While dividing his time between Munich and Murnau, Kandinsky participated actively in the intellectual and cultural life of both cities. He enjoyed a fascinating circle of friends, including the Russians Alexei Jawlensky and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, Franz Marc and August Macke, as well as Paul Klee. Kandinsky was also a correspondent to a Russian journal Apollon, reporting on cultural life in Germany and often contributed to exhibitions both in Russia and Germany. In 1911, he cofounded with Franz Marc an association of progressive artists ?Der Blaue Reiter? and a year later produced a compendium of writings on art and music ?Der Blaue Reiter Almanach?. He also met Arnold Schoenberg at this time. Although the outbreak of the First World War forced Kandinsky?s return to Russia in 1915 and interrupted the creative dialogue with Schoenberg, Kandinsky?s music-painting connection did not end, but continued after his seven year interlude in Russia, well into his Bauhaus years.

Many of Kandinsky's paintings and graphic works of the Bauhaus period of 1922 to 1933, as well as his second seminal treatise on art Point and Line to Plane (begun in 1914 and finally published in 1926), present a later aspect of his fascination with musical counterparts in painting. They also continue his aspiration of creating art that would be expressive of the theme of cosmology. As he stated in On the Spiritual in Art, painting evolves in the same way as the cosmos. Kandinsky desired to develop a cosmic and aesthetic model based on music and the analogy of geometric and harmonic principles that underlie the concept of celestial harmony, the theory that had been first formulated by Pythagoras and Plato and continued through to the 19th century revival by Helmholtz. Such cosmic implications address the distances among the planets and planetary system and dictate the use of circular elements as the symbols of the ultimate perfection of creation. It is clear that through these ideas Kandinsky aspired to create a pictorial universe that would reflect what he defined as the ?music of the spheres? in a metaphorical sense.

In retrospect, Kandinsky?s creative trajectory develops from his figurative style of the Blaue Reiter period to the early abstractions of 1913-1914, then to a geometric idiom, stimulated by the Russian years of 1915 to 1921, when he participated in the Russian avant-garde activities. This geometric concentration continued at the Bauhaus and then in Paris where it underwent...

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)

Rigide et courbé

signed with monogram and dated '35' (lower left)

oil and sand on canvas

44 7/8 x 63 7/8 in. (114 x 162.4 cm.)

Executed in Paris, December 1935

Provenance

Solomon R. Guggenheim, New York (acquired from the artist, 1936).

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York (gift from the above, 1937); sale, Sotheby's & Co., London, 30 June 1964, lot 47.

Acquired at the above sale by the family of the present owner.

View Special Publication: Wassily Kandinsky?s Rigide et courbé

PROPERTY FROM AN IMPORTANT PRIVATE AMERICAN COLLECTION

The name of Wassily Kandinsky is instantly connected with the creation of abstract art and the compositional expression through brilliant color and non-objective forms. His invention of abstraction in the second decade of the 20th century resulted from a protracted search for ?pure painting? and it marked a decisive turning point in the development of modernism. It signified a revolutionary break with the established artistic values of Western art, dominant since the Renaissance, based on representation of nature and traditional perspective. Searching to free himself from these pictorial restrictions, and psychologically and philosophically dissatisfied with the prevalent theories of the 19th century positivism and materialism, Kandinsky aspired to find a new mode of visual expression that would introduce a spiritual element into art and life, while being compatible with and expressive of the new, contemporary world. Like his near contemporaries Kazimir Malevich in Russia and Piet Mondrian in Paris, also striving for the absolute in art, Kandinsky evolved his very personal and radical language of color, form and composition.

Kandinsky intended to enter an academic career having studied law, economics and ethnography at the University of Moscow. Yet, in 1896, at the rather late age of thirty, he made the momentous decision to become an artist and moved to Munich to study. Three unexpected experiences prompted that fortuitous decision. First, the discovery of a Claude Monet painting of a grainstack at the French Industrial and Art Exhibition in Moscow in 1896, in front of which he responded emotionally before even recognizing the subject of the picture. Second, the sight of one of his own paintings placed sideways on an easel created a strong emotional response, and at that moment Kandinsky realized that it was actually not necessary to recognize the subject in the composition. And third, his aesthetic impressions from an 1889 trip as an ethnographer for the Russian Imperial Society of Friends of Natural History, Anthropology and Ethnography which took him to the remote region of Vologda in northern Russia. The area was inhabited by the ancient Finno-Ugric Zyrian tribes, whose laws and customs Kandinsky travelled to study. It opened his eyes to the beauty of popular art, which surrounded him in the houses of the local people, which were decorated with brightly colored furniture and painted sculptural forms. Kandinsky then became aware of the impact of color and forms that created a tumultuous visual space and in turn this actively affected his perceptual and emotional experience. The recollection of this event remained with him throughout his creative life and stimulated his desire to arrive at a pictorial idiom which would offer the viewer the same sensation of finding himself ?within the picture,? surrounded by a riot of colors and abstract forms.

The artist?s path to abstraction was complex, marked by sequential periods of transition and experimentation, intellectual and pictorial shifts as well as creative diversity. He supplemented his changing pictorial language by extensive writings on art, contained in his two major treatises On the Spiritual in Art: And Painting in Particular, published in 1912, and Point and Line To Plane, published in 1926.

The summer of 1908 marked the moment of dramatic change in Kandinsky?s style, which was originally rooted in the dark manner of the Munich School. These early works were inflected by the influences of Post-Impressionism, and the widely popular idiom of Jugendstil. What contributed to his ?awakening? in 1908 were his trips not only through Russia but also to Holland and Italy, as well as North Africa. Each trip immersed Kandinsky in the force of color as a visual and emotional factor. It was at this time that he began writing a theory of colors. During his stay in France with his companion-painter Gabrielle Münter (in 1906 to 1907) Kandinsky had also discovered the brilliantly hued work of Henri Matisse and other Fauves, which further cemented his affinity for color as a principal compositional and structural element. Upon his return to Munich that emphasis on color became the driving force behind Kandinsky?s work. Initially, the striking colors defined recognizable imagery. Increasingly though, from late 1909, that recognizable imagery began to become more abstracted or veiled by employing thin, cursory lines and brush-strokes where color was no longer confined to form but effectively created form.

Another vital and far-reaching aspect of Kandinsky?s art theory and practice was his interest in music and the theories of synesthesia or cross-sensory metaphors and correspondences between color and sound or word and image. Kandinsky?s fascination with the emotional power of music informs the complexity of his art and his attitudes to musical and visual concepts of structure and harmony of the composition. In the conclusion to the On the Spiritual he assigns to his works titles such Impressions, Improvisations and Compositions, a clear and simple reference to music. In search of the new pictorial idiom adequate to what he called ?an Epoch of the Great Spiritual?. Kandinsky believed this new aesthetic ought to reflect both the internal and external elements: the internal meant emotions or ?vibrations? of the soul while the external meant the innovative visual form. That, according to Kandinsky?s vision, could only be achieved through a visual language not tied down to the forms of reality. Like music that speaks ?to the soul? through abstract means, the visual art should aspire to create means of expression parallel to those of music. Ever since he heard Wagner?s ?Lohengrin? at the Imperial Theatre in 1896, Kandinsky felt special attraction to Wagner, whose music was greatly admired by the Symbolists for its idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk that embraced word, music, and the visual arts. Moreover, French, Belgian, and Russian symbolist theories of synesthesia, dominant at the end of the 19th century, heightened Kandinsky?s interest in the affinities between painting and music. They drew upon the theory of correspondences already formulated in the mid-19th century by the critic, poet and writer Charles Baudelaire.

Additional sources of his inspiration were the color theories of Goethe and Hermann Helmholtz, as well as other contemporaneous European and Russian scientific and Theosophist teachings. Kandinsky was conversant with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, theosophist writings and teachings of Madame Helena Blavatsky, and lectures by Rudolf Steiner. He closely followed Russian theories of mysticism, particularly those of Soloview and Dmitri Merezhkovsky. Furthermore, the music of Arnold Schoenberg and his Theory of Harmony, as well as the principle of the ?emancipated dissonance,? emphasized Kandinsky?s affinity with musical language.

While dividing his time between Munich and Murnau, Kandinsky participated actively in the intellectual and cultural life of both cities. He enjoyed a fascinating circle of friends, including the Russians Alexei Jawlensky and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, Franz Marc and August Macke, as well as Paul Klee. Kandinsky was also a correspondent to a Russian journal Apollon, reporting on cultural life in Germany and often contributed to exhibitions both in Russia and Germany. In 1911, he cofounded with Franz Marc an association of progressive artists ?Der Blaue Reiter? and a year later produced a compendium of writings on art and music ?Der Blaue Reiter Almanach?. He also met Arnold Schoenberg at this time. Although the outbreak of the First World War forced Kandinsky?s return to Russia in 1915 and interrupted the creative dialogue with Schoenberg, Kandinsky?s music-painting connection did not end, but continued after his seven year interlude in Russia, well into his Bauhaus years.

Many of Kandinsky's paintings and graphic works of the Bauhaus period of 1922 to 1933, as well as his second seminal treatise on art Point and Line to Plane (begun in 1914 and finally published in 1926), present a later aspect of his fascination with musical counterparts in painting. They also continue his aspiration of creating art that would be expressive of the theme of cosmology. As he stated in On the Spiritual in Art, painting evolves in the same way as the cosmos. Kandinsky desired to develop a cosmic and aesthetic model based on music and the analogy of geometric and harmonic principles that underlie the concept of celestial harmony, the theory that had been first formulated by Pythagoras and Plato and continued through to the 19th century revival by Helmholtz. Such cosmic implications address the distances among the planets and planetary system and dictate the use of circular elements as the symbols of the ultimate perfection of creation. It is clear that through these ideas Kandinsky aspired to create a pictorial universe that would reflect what he defined as the ?music of the spheres? in a metaphorical sense.

In retrospect, Kandinsky?s creative trajectory develops from his figurative style of the Blaue Reiter period to the early abstractions of 1913-1914, then to a geometric idiom, stimulated by the Russian years of 1915 to 1921, when he participated in the Russian avant-garde activities. This geometric concentration continued at the Bauhaus and then in Paris where it underwent...