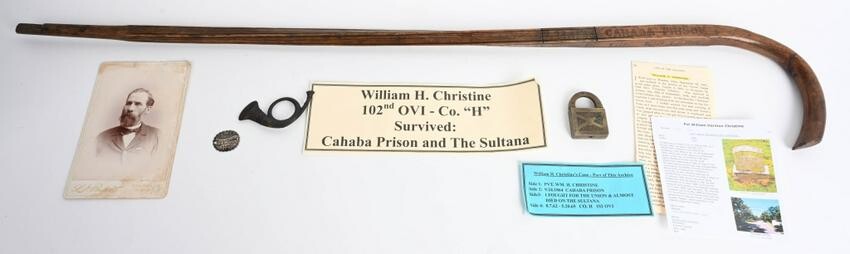

CIVIL WAR USS SULTANA SURVIVOR CARVED WALKING CANE

Grouping belonging to a member of the 102nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and a survivor of Cahaba Prison and the USS Sultana, the worst US Maritime disaster is US History. The grouping consist if his walking cane standing 37 inches tall with the inscription Pvt. William H. Christine 8.7.62 - 5.20.65 CO. H. 102 OVI 9.24.1864 CAHABA PRISON I FOUGHT FOR THE UNION & ALMOST DIED ON THE SULTANA. Cane is in excellent condition. 2) Pvt. William H. Christine Infantry Horn 3) Id'ed tag from the International Odd Fellows named to W. H. Christine 319 E. Spring Columbus Ohio. 4) Albumen of Private Christine wearing his GAR uniform named to the reverse. 5) Small brass luggage pad lock. Sultana was a Mississippi River side-wheel steamboat, which exploded on April 27, 1865, in the worst maritime disaster in United States history. Constructed of wood in 1863 by the John Litherbury Boatyard in Cincinnati, she was intended for the lower Mississippi cotton trade. The steamer registered 1,719 tons and normally carried a crew of 85. For two years, she ran a regular route between St. Louis and New Orleans, and was frequently commissioned to carry troops. Although designed with a capacity of only 376 passengers, she was carrying 2,137 when three of the boat's four boilers exploded and she burned to the waterline and sank near Memphis, Tennessee. The disaster was overshadowed in the press by events surrounding the end of the American Civil War, including the killing of President Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth just the day before, and no one was ever held accountable for the tragedy. Disaster POW Camp Fisk, Four Mile Bridge, Vicksburg, Mississippi April 1865. Standing 2nd from left is Maj. William R. Walls, 9th IN Cav.; Standing 4th From Left is Lt. Frederick A. Roziene, 49th USCT; Standing 5th from left is Maj Frank E. Miller, 66th USCT; Seated at table at left is Capt Archie C. Fisk, Ass't. Adj. Gen. Dept. of Vicksburg; Seated at table at right is Lt. Col. Howard A.M. Henderson, Exchange Agent (CSA); Standing 5th from right Lt. Edwin L. Davenport, 52d USCT; standing 4th from right is Col. Nathaniel G. Watts, Exchange Agent (CSA); Standing 3rd from right Capt. Reuben B. Hatch, Chief Quartermaster, Dept. of Vicksburg; Standing 2nd from right Rev Charles Kimball Marshall. Background Under the command of Captain James Cass Mason of St. Louis, Sultana left St. Louis on April 13, 1865 bound for New Orleans, Louisiana. On the morning of April 15, she was tied up at Cairo, Illinois, when word reached the city that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford's Theater. Immediately, Captain Mason grabbed an armload of Cairo newspapers and headed south to spread the news, knowing that telegraphic communication with the South had been almost totally cut off because of the war. Upon reaching Vicksburg, Mississippi, Mason was approached by Captain Reuben Hatch, the chief quartermaster at Vicksburg. Hatch had a deal for Mason. Thousands of recently released Union prisoners of war that had been held by the Confederacy at the prison camps of Cahaba near Selma, Alabama, and Andersonville, in southwest Georgia, had been brought to a small parole camp outside of Vicksburg to await release to the North. The U.S. government would pay $2.75 per enlisted man and $8 per officer to any steamboat captain who would take a group north. Knowing that Mason was in need of money, Hatch suggested that he could guarantee Mason a full load of about 1,400 prisoners if Mason would agree to give him a kickback. Hoping to gain much money through this deal, Mason quickly agreed to the offered bribe. Leaving Vicksburg, Sultana traveled down river to New Orleans, continuing to spread the news of Lincoln's assassination. On April 21, 1865 Sultana left New Orleans with about 70 cabin and deck passengers, and a small amount of livestock. She also carried a crew of About ten hours south of Vicksburg, one of Sultana's four boilers sprang a leak. Under reduced pressure, the steamboat limped into Vicksburg to get the boiler repaired and to pick up her promised load of prisoners. Faulty boiler repair While the paroled prisoners, primarily from the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia, were brought from the parole camp to Sultana, a mechanic was brought down to work on the leaky boiler. Although the mechanic wanted to cut out and replace a ruptured seam, Mason knew that such a job would take a few days and cost him his precious load of prisoners. By the time the repairs would be completed, the prisoners would have been sent home on other boats. Instead, Mason and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, convinced the mechanic to make temporary repairs, hammering back the bulged boiler plate and riveting a patch of lesser thickness over the seam. Instead of taking two or three days, the temporary repair took only one. During her time in port, and while the repairs were being made, Sultana took on the paroled prisoners. Overloaded Although Hatch had suggested that Mason might get as many as 1,400 released Union prisoners, a mix-up with the parole camp books and suspicion of bribery from other steamboat captains caused the Union officer in charge of the loading, Capt. George Augustus Williams, to place every man at the parole camp on board Sultana, believing the number to be less than 1,500. Although Sultana had a legal capacity of only 376, by the time she backed away from Vicksburg on the night of April 24, 1865, she was severely overcrowded with 1,960 paroled prisoners, 22 guards from the 58th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 70 paying cabin passengers, and 85 crew members, a total of 2,137 people. Many of the paroled prisoners had been weakened by their incarceration in the Confederate prison camps and associated illnesses but had managed to gain some strength while waiting at the parole camp to be officially released. The men were packed into every available space, and the overflow was so severe that in some places, the decks began to creak and sag and had to be supported with heavy wooden beams. Sultana spent two days traveling upriver, fighting against one of the worst spring floods in the river's history. At some places, the river overflowed the banks and spread out three miles wide. Trees along the river bank were almost completely covered, until only the very tops of the trees were visible above the swirling, powerful water. On April 26, Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas, where photographer Thomas W. Bankes took a picture of the grossly overcrowded vessel. Near 7:00 p.m., Sultana reached Memphis, Tennessee and the crew began unloading 120 tons of sugar from the hold. Near midnight, Sultana left Memphis, perhaps leaving behind about 200 men. She then went a short distance upriver to take on a new load of coal from some coal barges, and then at about 1:00 a.m. started north again. Explosion Near 2:00 a.m. on April 27, 1865, when Sultana was just seven miles north of Memphis, its boilers suddenly exploded. First one boiler exploded, followed a split second later by two more. The enormous explosion of steam came from the top rear of the boilers and went upward at a 45-degree angle, tearing through the crowded decks above, and completely demolishing the pilothouse. Without a pilot to steer the boat, Sultana became a drifting, burning hulk. The terrific explosion flung some of the deck passengers into the water and destroyed a large section of the boat. The twin smokestacks toppled over, the right-hand one backwards into the blasted hole, and the left-hand one forward onto the crowded forward section of the upper deck. The forward part of the upper deck was crushed down onto the middle deck, killing and trapping many in the wreckage. Fortunately the sturdy railings around the twin openings of the main stairway prevented the upper deck from crushing down completely onto the middle deck. Those men sleeping around the twin openings quickly crawled under the wreckage and down the main stairs. Further back, the collapsing decks formed a slope that led down into the exposed furnace boxes. The broken wood caught fire and turned the remaining superstructure into an inferno. Survivors of the explosion panicked and raced for the safety of the water but in their weakened condition soon ran out of strength and began to cling to each other. Whole groups went down together. Rescue attempts While this fight for survival was taking place, the southbound steamer Bostona (No. 2), built in 1860 but coming down river on her maiden voyage after being refurbished, arrived at about 2:30 a.m., a half hour after the explosion, and arrived at the site of the burning wreck to rescue scores of survivors. At the same time, dozens of people began to float past the Memphis waterfront, calling for help until they were noticed by the crews of docked steamboats and U.S. warships, who immediately set about rescuing the half-drowned victims. Eventually, the hulk of Sultana drifted about six miles to the west bank of the river, and sank at around 9:00 a.m. near Mound City and present-day Marion, Arkansas, about seven hours after the explosion. Other vessels joined the rescue, including the steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocahontas, the navy ironclad Essex and the side wheel gunboat USS Tyler. Passengers who survived the initial explosion had to risk their lives in the icy spring runoff of the Mississippi or burn with the boat. Many died of drowning or hypothermia. Some survivors were plucked from the tops of semi-submerged trees along the Arkansas shore. Bodies of victims continued to be found down river for months, some as far as Vicksburg. Many bodies were never recovered. Most of Sultana's officers, including Captain Mason, were among those who perished. Casualties The exact death toll is unknown, although the most recent evidence indicates 1,168. On May 19, 1865, less than a month after the disaster, Brig. Gen. William Hoffman, Commissary General of Prisoners, who...

[ translate ]View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Grouping belonging to a member of the 102nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and a survivor of Cahaba Prison and the USS Sultana, the worst US Maritime disaster is US History. The grouping consist if his walking cane standing 37 inches tall with the inscription Pvt. William H. Christine 8.7.62 - 5.20.65 CO. H. 102 OVI 9.24.1864 CAHABA PRISON I FOUGHT FOR THE UNION & ALMOST DIED ON THE SULTANA. Cane is in excellent condition. 2) Pvt. William H. Christine Infantry Horn 3) Id'ed tag from the International Odd Fellows named to W. H. Christine 319 E. Spring Columbus Ohio. 4) Albumen of Private Christine wearing his GAR uniform named to the reverse. 5) Small brass luggage pad lock. Sultana was a Mississippi River side-wheel steamboat, which exploded on April 27, 1865, in the worst maritime disaster in United States history. Constructed of wood in 1863 by the John Litherbury Boatyard in Cincinnati, she was intended for the lower Mississippi cotton trade. The steamer registered 1,719 tons and normally carried a crew of 85. For two years, she ran a regular route between St. Louis and New Orleans, and was frequently commissioned to carry troops. Although designed with a capacity of only 376 passengers, she was carrying 2,137 when three of the boat's four boilers exploded and she burned to the waterline and sank near Memphis, Tennessee. The disaster was overshadowed in the press by events surrounding the end of the American Civil War, including the killing of President Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth just the day before, and no one was ever held accountable for the tragedy. Disaster POW Camp Fisk, Four Mile Bridge, Vicksburg, Mississippi April 1865. Standing 2nd from left is Maj. William R. Walls, 9th IN Cav.; Standing 4th From Left is Lt. Frederick A. Roziene, 49th USCT; Standing 5th from left is Maj Frank E. Miller, 66th USCT; Seated at table at left is Capt Archie C. Fisk, Ass't. Adj. Gen. Dept. of Vicksburg; Seated at table at right is Lt. Col. Howard A.M. Henderson, Exchange Agent (CSA); Standing 5th from right Lt. Edwin L. Davenport, 52d USCT; standing 4th from right is Col. Nathaniel G. Watts, Exchange Agent (CSA); Standing 3rd from right Capt. Reuben B. Hatch, Chief Quartermaster, Dept. of Vicksburg; Standing 2nd from right Rev Charles Kimball Marshall. Background Under the command of Captain James Cass Mason of St. Louis, Sultana left St. Louis on April 13, 1865 bound for New Orleans, Louisiana. On the morning of April 15, she was tied up at Cairo, Illinois, when word reached the city that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford's Theater. Immediately, Captain Mason grabbed an armload of Cairo newspapers and headed south to spread the news, knowing that telegraphic communication with the South had been almost totally cut off because of the war. Upon reaching Vicksburg, Mississippi, Mason was approached by Captain Reuben Hatch, the chief quartermaster at Vicksburg. Hatch had a deal for Mason. Thousands of recently released Union prisoners of war that had been held by the Confederacy at the prison camps of Cahaba near Selma, Alabama, and Andersonville, in southwest Georgia, had been brought to a small parole camp outside of Vicksburg to await release to the North. The U.S. government would pay $2.75 per enlisted man and $8 per officer to any steamboat captain who would take a group north. Knowing that Mason was in need of money, Hatch suggested that he could guarantee Mason a full load of about 1,400 prisoners if Mason would agree to give him a kickback. Hoping to gain much money through this deal, Mason quickly agreed to the offered bribe. Leaving Vicksburg, Sultana traveled down river to New Orleans, continuing to spread the news of Lincoln's assassination. On April 21, 1865 Sultana left New Orleans with about 70 cabin and deck passengers, and a small amount of livestock. She also carried a crew of About ten hours south of Vicksburg, one of Sultana's four boilers sprang a leak. Under reduced pressure, the steamboat limped into Vicksburg to get the boiler repaired and to pick up her promised load of prisoners. Faulty boiler repair While the paroled prisoners, primarily from the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia, were brought from the parole camp to Sultana, a mechanic was brought down to work on the leaky boiler. Although the mechanic wanted to cut out and replace a ruptured seam, Mason knew that such a job would take a few days and cost him his precious load of prisoners. By the time the repairs would be completed, the prisoners would have been sent home on other boats. Instead, Mason and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, convinced the mechanic to make temporary repairs, hammering back the bulged boiler plate and riveting a patch of lesser thickness over the seam. Instead of taking two or three days, the temporary repair took only one. During her time in port, and while the repairs were being made, Sultana took on the paroled prisoners. Overloaded Although Hatch had suggested that Mason might get as many as 1,400 released Union prisoners, a mix-up with the parole camp books and suspicion of bribery from other steamboat captains caused the Union officer in charge of the loading, Capt. George Augustus Williams, to place every man at the parole camp on board Sultana, believing the number to be less than 1,500. Although Sultana had a legal capacity of only 376, by the time she backed away from Vicksburg on the night of April 24, 1865, she was severely overcrowded with 1,960 paroled prisoners, 22 guards from the 58th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 70 paying cabin passengers, and 85 crew members, a total of 2,137 people. Many of the paroled prisoners had been weakened by their incarceration in the Confederate prison camps and associated illnesses but had managed to gain some strength while waiting at the parole camp to be officially released. The men were packed into every available space, and the overflow was so severe that in some places, the decks began to creak and sag and had to be supported with heavy wooden beams. Sultana spent two days traveling upriver, fighting against one of the worst spring floods in the river's history. At some places, the river overflowed the banks and spread out three miles wide. Trees along the river bank were almost completely covered, until only the very tops of the trees were visible above the swirling, powerful water. On April 26, Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas, where photographer Thomas W. Bankes took a picture of the grossly overcrowded vessel. Near 7:00 p.m., Sultana reached Memphis, Tennessee and the crew began unloading 120 tons of sugar from the hold. Near midnight, Sultana left Memphis, perhaps leaving behind about 200 men. She then went a short distance upriver to take on a new load of coal from some coal barges, and then at about 1:00 a.m. started north again. Explosion Near 2:00 a.m. on April 27, 1865, when Sultana was just seven miles north of Memphis, its boilers suddenly exploded. First one boiler exploded, followed a split second later by two more. The enormous explosion of steam came from the top rear of the boilers and went upward at a 45-degree angle, tearing through the crowded decks above, and completely demolishing the pilothouse. Without a pilot to steer the boat, Sultana became a drifting, burning hulk. The terrific explosion flung some of the deck passengers into the water and destroyed a large section of the boat. The twin smokestacks toppled over, the right-hand one backwards into the blasted hole, and the left-hand one forward onto the crowded forward section of the upper deck. The forward part of the upper deck was crushed down onto the middle deck, killing and trapping many in the wreckage. Fortunately the sturdy railings around the twin openings of the main stairway prevented the upper deck from crushing down completely onto the middle deck. Those men sleeping around the twin openings quickly crawled under the wreckage and down the main stairs. Further back, the collapsing decks formed a slope that led down into the exposed furnace boxes. The broken wood caught fire and turned the remaining superstructure into an inferno. Survivors of the explosion panicked and raced for the safety of the water but in their weakened condition soon ran out of strength and began to cling to each other. Whole groups went down together. Rescue attempts While this fight for survival was taking place, the southbound steamer Bostona (No. 2), built in 1860 but coming down river on her maiden voyage after being refurbished, arrived at about 2:30 a.m., a half hour after the explosion, and arrived at the site of the burning wreck to rescue scores of survivors. At the same time, dozens of people began to float past the Memphis waterfront, calling for help until they were noticed by the crews of docked steamboats and U.S. warships, who immediately set about rescuing the half-drowned victims. Eventually, the hulk of Sultana drifted about six miles to the west bank of the river, and sank at around 9:00 a.m. near Mound City and present-day Marion, Arkansas, about seven hours after the explosion. Other vessels joined the rescue, including the steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocahontas, the navy ironclad Essex and the side wheel gunboat USS Tyler. Passengers who survived the initial explosion had to risk their lives in the icy spring runoff of the Mississippi or burn with the boat. Many died of drowning or hypothermia. Some survivors were plucked from the tops of semi-submerged trees along the Arkansas shore. Bodies of victims continued to be found down river for months, some as far as Vicksburg. Many bodies were never recovered. Most of Sultana's officers, including Captain Mason, were among those who perished. Casualties The exact death toll is unknown, although the most recent evidence indicates 1,168. On May 19, 1865, less than a month after the disaster, Brig. Gen. William Hoffman, Commissary General of Prisoners, who...

[ translate ]