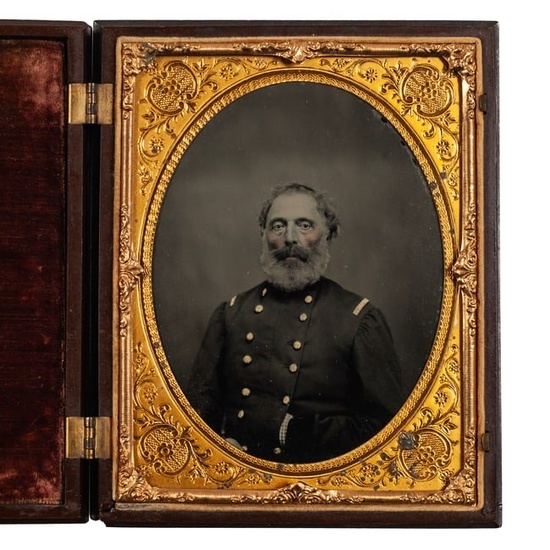

Confederate General John B. Floyd

Half plate studio ambrotype with hand tinting and gilding. [Knoxville, Tennessee], [February-March 1862]. Housed in full thermoplastic case with a military monument vignette. With an excellent period ink inscription by General Floyd’s Adjutant General Clarence Derrick providing the image’s history: “Genl. John B. Floyd / Taken at Knoxville / during Civil War / whilst en route from / Nashville & Chattanooga / to / Virginia after / Battle of Fort Donelson / Given to his A.A. Genl. / C. Derrick.”

A poignant portrait of General John B. Floyd not long after his loss at Fort Donelson, a crucial Confederate defeat. Here, the general looks wearily directly at the lens, giving an inescapable look of defeat.

This large, half-plate ambrotype captures Floyd wearing his double-breasted brigadier general’s coat with buttons in groups of two and narrow gold braid shoulder straps (which would have held the general’s full-dress epaulets) neatly hand-gilt. In a pose typical of Napoleon and other statesman of the era, the general’s hand is thrust into his coat, revealing a sliver of his checkered shirt cuff. The coat is dark and was likely a dark blue in keeping with Virginia’s 1858 decision to follow U.S. uniform regulations. The photographer delicately tinted Floyd’s cheeks, but this does nothing to conceal his doleful expression.

This important portrait was taken at a pivotal moment in Floyd’s life. The note records that it was captured after his defeat at Fort Donelson, the subsequent evacuation of Nashville, and his dismissal from command by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The manuscript note is made to his Adjutant General Clarence Derrick, likely as a parting gift. Derrick was a West Point graduate of 1861, ranking fourth in his class. This gift is a clear indication of Derrick's utility and service to Floyd, who owed his rank and command to political rather than military experience.

Born near Blacksburg, Virginia in June 1806, Floyd was the son of later Congressman and Virginia Governor John Floyd (1783-1837.) A graduate of South Carolina College (now University of South Carolina), he benefitted from strong political connections through his father, a brother who served in the Virginia General Assembly, a sister married to a U.S. Senator, and his wife (also a cousin), whose father was a congressman and whose brother was a U.S. senator. Admitted to the Virginia bar in 1828, Floyd practiced law in Abingdon, pursued some unsuccessful business ventures in Arkansas, and then returned to law and politics in Virginia in 1839. He was elected to the Abingdon Town Council in 1843 and twice to the Virginia House of Delegates, which also elected him Governor in 1849. In politics, Floyd spearheaded some reforms giving greater representation to Virginia’s western counties and removing property qualification for voting. He continued to be unlucky in business, suffering losses in a newspaper venture in the 1850s, but forged ahead in politics, serving as an elector for Buchanan in 1856 and joining Buchanan’s cabinet as Secretary of War in March of 1857. His performance in this role was controversial, with his tendency toward disorganization illustrated by his mishandling of the Mormon Expedition. Floyd was also involved in a scandal involving embezzlement of Indian Agency bonds in the custody of the War Department, though it was never proven that he himself had profited.

He certainly enjoyed cozy relationships with government contractors, often advancing payments and arranging favorable terms. Floyd's list of beneficiaries included Samuel Colt. Col. H.K. Craig, Chief of Ordnance, maintained that Floyd removed him as part of a scheme to allow Colt to continue selling pistols to the U.S. government at twice what he charged Great Britain. Once again, it was not clear if Floyd had profited personally, but Colt thought well enough of him to present an elegantly cased pistol to Floyd and his wife. It did not help appearances, or relations with some future Confederate commanders, that he also promoted a relative, Joseph E. Johnston, to Quartermaster General, a position of great financial responsibility.

More damning was Floyd’s handling of U.S. arms distributions after the John Brown raid, transfers of weapons from northern to southern arsenals that came to be seen as part of broader plan after the war began. Grant later asserted that Floyd not only had a hand in placing small arms and heavy ordnance within the grasp of Confederate forces in preparation for war, but also widely dispersed Federal troops to make them easier to capture. All of this, and ongoing U.S. congressional investigations, made Floyd more than a little uneasy at the prospect of falling into government hands once the fighting began. Appointed a Major General in the Virginia state forces when the war commenced, he received a commission as Brigadier General in the Confederate Army and initially served under Lee in the unsuccessful campaign in western Virginia. Floyd routed a smaller Union force at Kessler’s Cross Lanes in August 1861, and was wounded in battle in September at Carnifex Ferry. But despite repelling initial Union attacks in that battle, he retreated, blaming a lack of cooperation by co-commander Henry A. Wise.

Jefferson Davis thought well enough of Floyd, however, to remove Wise and later send Floyd west in January 1862 to Albert Sidney Johnston, where he was given a division command. With Beauregard sick, Floyd was the senior officer available for command of Fort Donelson, near the Tennessee-Kentucky border, defending the Cumberland River, and covering Nashville and middle Tennessee. Floyd arrived on February 13, two days after Grant had already begun preliminary attacks against the fort after his success at Fort Henry. Floyd was the most senior general on the Cumberland River, however his experience was political, and therefore mostly deferred to Generals Gideon Pillow and Simon Bolivar Buckner in the defense of the fort. It was decided that Pillow would lead a breakout attempt to evacuate troops to Nashville. Despite initial success, Grant repulsed the charge. The Confederates failed to break through the Federal lines and Pillow vacillated on the plan. General Pillow escaped during the night and the next morning by commandeering two steamboats agreement to evacuate himself, staff and many of his Virginia troops to Nashville. General Buckner was left to surrender unconditionally to General Grant.

The surrender deprived Johnston of some 12,000 troops, led to the evacuation of Nashville in late February, and Columbus, Kentucky, in early March, ceding most of Tennessee and Kentucky to Federal control. Davis dispensed with a court of inquiry and simply removed Floyd from command March 11.Â

[Civil War, Confederate, Union, Historic Photography, Cased Images, Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Texas, Cavalry]

Bid on this lot

Estimate

Reserve

Time, Location

Auction House

Half plate studio ambrotype with hand tinting and gilding. [Knoxville, Tennessee], [February-March 1862]. Housed in full thermoplastic case with a military monument vignette. With an excellent period ink inscription by General Floyd’s Adjutant General Clarence Derrick providing the image’s history: “Genl. John B. Floyd / Taken at Knoxville / during Civil War / whilst en route from / Nashville & Chattanooga / to / Virginia after / Battle of Fort Donelson / Given to his A.A. Genl. / C. Derrick.”

A poignant portrait of General John B. Floyd not long after his loss at Fort Donelson, a crucial Confederate defeat. Here, the general looks wearily directly at the lens, giving an inescapable look of defeat.

This large, half-plate ambrotype captures Floyd wearing his double-breasted brigadier general’s coat with buttons in groups of two and narrow gold braid shoulder straps (which would have held the general’s full-dress epaulets) neatly hand-gilt. In a pose typical of Napoleon and other statesman of the era, the general’s hand is thrust into his coat, revealing a sliver of his checkered shirt cuff. The coat is dark and was likely a dark blue in keeping with Virginia’s 1858 decision to follow U.S. uniform regulations. The photographer delicately tinted Floyd’s cheeks, but this does nothing to conceal his doleful expression.

This important portrait was taken at a pivotal moment in Floyd’s life. The note records that it was captured after his defeat at Fort Donelson, the subsequent evacuation of Nashville, and his dismissal from command by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The manuscript note is made to his Adjutant General Clarence Derrick, likely as a parting gift. Derrick was a West Point graduate of 1861, ranking fourth in his class. This gift is a clear indication of Derrick's utility and service to Floyd, who owed his rank and command to political rather than military experience.

Born near Blacksburg, Virginia in June 1806, Floyd was the son of later Congressman and Virginia Governor John Floyd (1783-1837.) A graduate of South Carolina College (now University of South Carolina), he benefitted from strong political connections through his father, a brother who served in the Virginia General Assembly, a sister married to a U.S. Senator, and his wife (also a cousin), whose father was a congressman and whose brother was a U.S. senator. Admitted to the Virginia bar in 1828, Floyd practiced law in Abingdon, pursued some unsuccessful business ventures in Arkansas, and then returned to law and politics in Virginia in 1839. He was elected to the Abingdon Town Council in 1843 and twice to the Virginia House of Delegates, which also elected him Governor in 1849. In politics, Floyd spearheaded some reforms giving greater representation to Virginia’s western counties and removing property qualification for voting. He continued to be unlucky in business, suffering losses in a newspaper venture in the 1850s, but forged ahead in politics, serving as an elector for Buchanan in 1856 and joining Buchanan’s cabinet as Secretary of War in March of 1857. His performance in this role was controversial, with his tendency toward disorganization illustrated by his mishandling of the Mormon Expedition. Floyd was also involved in a scandal involving embezzlement of Indian Agency bonds in the custody of the War Department, though it was never proven that he himself had profited.

He certainly enjoyed cozy relationships with government contractors, often advancing payments and arranging favorable terms. Floyd's list of beneficiaries included Samuel Colt. Col. H.K. Craig, Chief of Ordnance, maintained that Floyd removed him as part of a scheme to allow Colt to continue selling pistols to the U.S. government at twice what he charged Great Britain. Once again, it was not clear if Floyd had profited personally, but Colt thought well enough of him to present an elegantly cased pistol to Floyd and his wife. It did not help appearances, or relations with some future Confederate commanders, that he also promoted a relative, Joseph E. Johnston, to Quartermaster General, a position of great financial responsibility.

More damning was Floyd’s handling of U.S. arms distributions after the John Brown raid, transfers of weapons from northern to southern arsenals that came to be seen as part of broader plan after the war began. Grant later asserted that Floyd not only had a hand in placing small arms and heavy ordnance within the grasp of Confederate forces in preparation for war, but also widely dispersed Federal troops to make them easier to capture. All of this, and ongoing U.S. congressional investigations, made Floyd more than a little uneasy at the prospect of falling into government hands once the fighting began. Appointed a Major General in the Virginia state forces when the war commenced, he received a commission as Brigadier General in the Confederate Army and initially served under Lee in the unsuccessful campaign in western Virginia. Floyd routed a smaller Union force at Kessler’s Cross Lanes in August 1861, and was wounded in battle in September at Carnifex Ferry. But despite repelling initial Union attacks in that battle, he retreated, blaming a lack of cooperation by co-commander Henry A. Wise.

Jefferson Davis thought well enough of Floyd, however, to remove Wise and later send Floyd west in January 1862 to Albert Sidney Johnston, where he was given a division command. With Beauregard sick, Floyd was the senior officer available for command of Fort Donelson, near the Tennessee-Kentucky border, defending the Cumberland River, and covering Nashville and middle Tennessee. Floyd arrived on February 13, two days after Grant had already begun preliminary attacks against the fort after his success at Fort Henry. Floyd was the most senior general on the Cumberland River, however his experience was political, and therefore mostly deferred to Generals Gideon Pillow and Simon Bolivar Buckner in the defense of the fort. It was decided that Pillow would lead a breakout attempt to evacuate troops to Nashville. Despite initial success, Grant repulsed the charge. The Confederates failed to break through the Federal lines and Pillow vacillated on the plan. General Pillow escaped during the night and the next morning by commandeering two steamboats agreement to evacuate himself, staff and many of his Virginia troops to Nashville. General Buckner was left to surrender unconditionally to General Grant.

The surrender deprived Johnston of some 12,000 troops, led to the evacuation of Nashville in late February, and Columbus, Kentucky, in early March, ceding most of Tennessee and Kentucky to Federal control. Davis dispensed with a court of inquiry and simply removed Floyd from command March 11.Â

[Civil War, Confederate, Union, Historic Photography, Cased Images, Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Texas, Cavalry]