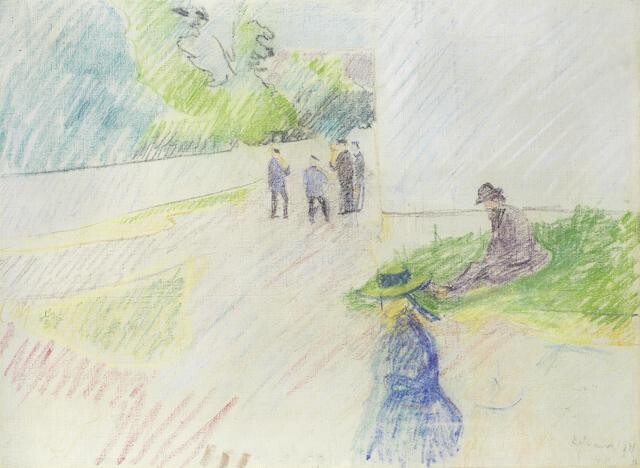

Edvard Munch, (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Sommer (Summer)

Sommer (Summer)

signed and dated 'E. Munch 1891' (lower right)

oil pastel and coloured crayon on canvas

54.6 x 74.3cm (21 1/2 x 29 1/4in).

Executed in 1891

Provenance

Harald Nørregaard Collection; his sale, Wangs Kunsthandel, Oslo, 26 September 1938, lot 23.

Kaare Berntsen AS Collection, Oslo, 1971 - 1973.

Anon. sale, Sotheby's, New York, 15 May 1980, lot 311.

Private collection, London.

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2014.

Exhibited

Oslo, Galleri KB-Kaare Berntsen, Edvard Munch, Oil Painting, Watercolours, Graphical works, 1971, no. 1 (titled ' Musicians in Nice').

Paris, Pinacothèque de Paris, Edvard Munch ou 'l'Anti-Cri', 19 February - 18 July 2010, no. 13.

Literature

G. Woll, Edvard Munch, Complete Paintings, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I, 1880 - 1897, London, 2009, no. 238 (illustrated p. 228).

'There should be no more paintings of people reading and women knitting. In future they should be of people who breathe, who feel emotions, who suffer and love' (E. Munch writing in St. Cloud, 1889, quoted in R. Stang, Edvard Munch, The Man and his Art, Oslo, 1977, p. 73).

The present work was executed in 1891 during a period of great change for Edvard Munch both in his artistic and personal life. In 1889 he returned to Paris thanks to a state scholarship provided by the Norwegian government and was to remain based in the capital for several years. In Paris Munch attended the demanding art school run by Léon Bonnart, a formidable tutor who had instructed some of Norway's best artists. 'Bonnart likes my drawings very much' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, ibid., p. 70) Munch was to write home; however, he found little stimulus in his teacher's drawing lessons and was soon in total opposition to Bonnart's conventional painting methods.

What was to inspire the young artist during his sojourn was his exposure to a vast array of modern European artists, encountered through his afternoon trips to the museums. At first it was the techniques of the French Impressionists, evinced in the works of Monet and Pissarro, which caught his eye, but during the autumn months of 1889 Munch also came into contact with French Post-Impressionists, most notably the works of Paul Gauguin and the later Nabis group, and their radical use of vibrant colour alongside a synthesis of line and form. Concurrently, Munch fell under the spell of the two great artistic and literary movements of the fin-de-siècle in France: Symbolism and Mysticism - an immersion which was to decisively launch his art from the limited confines of Naturalism into a heady world of spirituality, subjectivity and introspection.

The death of Munch's father in November 1889 also had a profound effect on the young artist. It was at this moment that he began to break free from his past and to confront the traumatic experiences of his early years. Installed during the winter of 1889 in St. Cloud, on the outskirts of Paris, Munch began to formulate a new artistic creed in which he rejected his former artistic instruction and began to offer a view of the world from an internal rather than external perspective. Just as the Impressionists had sought to capture the transience of light and atmospheric effects within their compositions, Munch endeavoured to seize the fleeting sensations of an emotion or feeling: 'It happened sometimes that I came across a landscape that I wanted to paint, perhaps when I was depressed or perhaps when I was in a good mood. I would go away and fetch my easel put it up, and paint what I saw. I often produced good paintings that way, but they never turned out the way I wanted. I never succeeded in painting the scene the way I have seen it, in the mood that I was in at the time. This often happened, and so, when it did, I began to scratch out what I had painted and try to recall my original mood, striving to capture that first impression' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, ibid., p. 73).

Executed in pastel and crayon, rather unusually, on primed canvas, Sommer conveys a sense of the artist working swiftly en plein air to capture the emotional import of his scene. Employing gestural strokes of pastel, Munch adeptly builds the composition through a sketchy application of line and pure colour. Munch was much ridiculed during his early career for this perceived lack of finish within his work but later this very quality came to be acknowledged by a number of scholars as the most classically Modernist aspect of his work. Munch himself did not distinguish between the values of painting or drawing: 'A charcoal drawing on a wall can be a greater work of art than the most perfectly executed painting' he once noted (E. Munch quoted in G. Woll, Edvard Munch, Complete Paintings, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I, 1880 1897, London, 2009, p. 22). Indeed, the simplification of technique was a deliberate device which served to distil the composition to the most essential elements thus imbuing it with a universality and timelessness.

In the present work, Munch concentrates the viewer's attention onto the positioning and relationship between the figures within the otherwise stark scene. His subjects, as one commentator has observed, are 'like actors on a stage...[who] express feelings and attitudes through pose and gesture' (G. Woll, ibid., p. 25). The woman to the foreground of the composition is depicted with slightly blurred contours as if she is walking purposely in front of the viewer, meanwhile the group of four musicians to the upper left appear animated as if mid-tune or in conversation. By contrast the solitary seated figure to the right, dressed in sombre black, adopts a more melancholic and lonesome air. His gently bowed head signifies his alienation from the other subjects and he appears pensive, as if lost in thought. Meanwhile, the composition of the work itself serves to further emphasise the sense of loss or lack within the scene, with the lower left quadrant strikingly void in comparison to the rest of the canvas.

In letters from later this year in 1891 Munch was to disclose his sense of isolation, and as such the male figure of Sommer can almost be viewed as a substitute for the artist himself. Upon arrival in Nice in the winter of 1891 he wrote to his friend Emmanuel Goldstein: 'I am finally in Nice, the city that I have dreamt of for so long... It is more beautiful here than I have ever dreamed. The Promenade des Anglais is most impressive with the wonderfully blue water on one side. The sea is such a fleeting shade of blue that it looks as though it has been painted with naptha. But how lonely it is I have long since stopped listening to the footsteps on the stair, as I know they are never for me' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, op. cit., p. 82).

View it on

Sale price

Time, Location

Auction House

Sommer (Summer)

Sommer (Summer)

signed and dated 'E. Munch 1891' (lower right)

oil pastel and coloured crayon on canvas

54.6 x 74.3cm (21 1/2 x 29 1/4in).

Executed in 1891

Provenance

Harald Nørregaard Collection; his sale, Wangs Kunsthandel, Oslo, 26 September 1938, lot 23.

Kaare Berntsen AS Collection, Oslo, 1971 - 1973.

Anon. sale, Sotheby's, New York, 15 May 1980, lot 311.

Private collection, London.

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2014.

Exhibited

Oslo, Galleri KB-Kaare Berntsen, Edvard Munch, Oil Painting, Watercolours, Graphical works, 1971, no. 1 (titled ' Musicians in Nice').

Paris, Pinacothèque de Paris, Edvard Munch ou 'l'Anti-Cri', 19 February - 18 July 2010, no. 13.

Literature

G. Woll, Edvard Munch, Complete Paintings, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I, 1880 - 1897, London, 2009, no. 238 (illustrated p. 228).

'There should be no more paintings of people reading and women knitting. In future they should be of people who breathe, who feel emotions, who suffer and love' (E. Munch writing in St. Cloud, 1889, quoted in R. Stang, Edvard Munch, The Man and his Art, Oslo, 1977, p. 73).

The present work was executed in 1891 during a period of great change for Edvard Munch both in his artistic and personal life. In 1889 he returned to Paris thanks to a state scholarship provided by the Norwegian government and was to remain based in the capital for several years. In Paris Munch attended the demanding art school run by Léon Bonnart, a formidable tutor who had instructed some of Norway's best artists. 'Bonnart likes my drawings very much' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, ibid., p. 70) Munch was to write home; however, he found little stimulus in his teacher's drawing lessons and was soon in total opposition to Bonnart's conventional painting methods.

What was to inspire the young artist during his sojourn was his exposure to a vast array of modern European artists, encountered through his afternoon trips to the museums. At first it was the techniques of the French Impressionists, evinced in the works of Monet and Pissarro, which caught his eye, but during the autumn months of 1889 Munch also came into contact with French Post-Impressionists, most notably the works of Paul Gauguin and the later Nabis group, and their radical use of vibrant colour alongside a synthesis of line and form. Concurrently, Munch fell under the spell of the two great artistic and literary movements of the fin-de-siècle in France: Symbolism and Mysticism - an immersion which was to decisively launch his art from the limited confines of Naturalism into a heady world of spirituality, subjectivity and introspection.

The death of Munch's father in November 1889 also had a profound effect on the young artist. It was at this moment that he began to break free from his past and to confront the traumatic experiences of his early years. Installed during the winter of 1889 in St. Cloud, on the outskirts of Paris, Munch began to formulate a new artistic creed in which he rejected his former artistic instruction and began to offer a view of the world from an internal rather than external perspective. Just as the Impressionists had sought to capture the transience of light and atmospheric effects within their compositions, Munch endeavoured to seize the fleeting sensations of an emotion or feeling: 'It happened sometimes that I came across a landscape that I wanted to paint, perhaps when I was depressed or perhaps when I was in a good mood. I would go away and fetch my easel put it up, and paint what I saw. I often produced good paintings that way, but they never turned out the way I wanted. I never succeeded in painting the scene the way I have seen it, in the mood that I was in at the time. This often happened, and so, when it did, I began to scratch out what I had painted and try to recall my original mood, striving to capture that first impression' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, ibid., p. 73).

Executed in pastel and crayon, rather unusually, on primed canvas, Sommer conveys a sense of the artist working swiftly en plein air to capture the emotional import of his scene. Employing gestural strokes of pastel, Munch adeptly builds the composition through a sketchy application of line and pure colour. Munch was much ridiculed during his early career for this perceived lack of finish within his work but later this very quality came to be acknowledged by a number of scholars as the most classically Modernist aspect of his work. Munch himself did not distinguish between the values of painting or drawing: 'A charcoal drawing on a wall can be a greater work of art than the most perfectly executed painting' he once noted (E. Munch quoted in G. Woll, Edvard Munch, Complete Paintings, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I, 1880 1897, London, 2009, p. 22). Indeed, the simplification of technique was a deliberate device which served to distil the composition to the most essential elements thus imbuing it with a universality and timelessness.

In the present work, Munch concentrates the viewer's attention onto the positioning and relationship between the figures within the otherwise stark scene. His subjects, as one commentator has observed, are 'like actors on a stage...[who] express feelings and attitudes through pose and gesture' (G. Woll, ibid., p. 25). The woman to the foreground of the composition is depicted with slightly blurred contours as if she is walking purposely in front of the viewer, meanwhile the group of four musicians to the upper left appear animated as if mid-tune or in conversation. By contrast the solitary seated figure to the right, dressed in sombre black, adopts a more melancholic and lonesome air. His gently bowed head signifies his alienation from the other subjects and he appears pensive, as if lost in thought. Meanwhile, the composition of the work itself serves to further emphasise the sense of loss or lack within the scene, with the lower left quadrant strikingly void in comparison to the rest of the canvas.

In letters from later this year in 1891 Munch was to disclose his sense of isolation, and as such the male figure of Sommer can almost be viewed as a substitute for the artist himself. Upon arrival in Nice in the winter of 1891 he wrote to his friend Emmanuel Goldstein: 'I am finally in Nice, the city that I have dreamt of for so long... It is more beautiful here than I have ever dreamed. The Promenade des Anglais is most impressive with the wonderfully blue water on one side. The sea is such a fleeting shade of blue that it looks as though it has been painted with naptha. But how lonely it is I have long since stopped listening to the footsteps on the stair, as I know they are never for me' (E. Munch quoted in R. Stang, op. cit., p. 82).