Exceptional Civil War Archive of John Merritt Morse, NH

Exceptional Civil War Archive of John Merritt Morse, NH 3rd Infantry and US Army Signal Corps

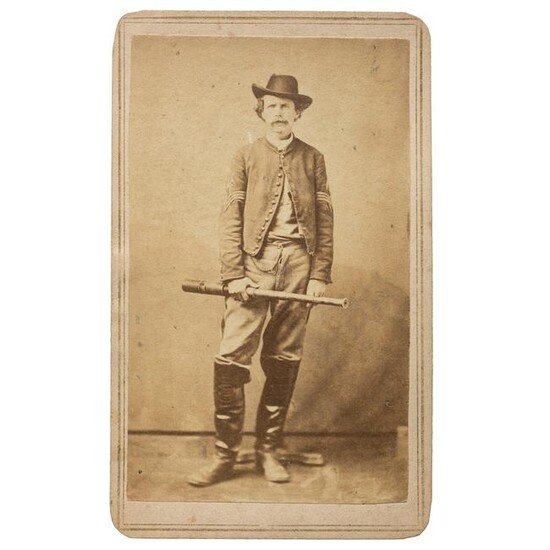

Lot of approximately 145 letters, most 4-8pp (1000+ pp total correspondence), many with original covers, spanning Oct 1862 - June 1865. All but approximately 5 letters written by John Merritt Morse (1832-1913) of Jefferson, NH to his family while serving with the NH 3rd Infantry and later the United States Army Signal Corps. Lot also includes 11 portrait CDVs of identified soldiers, many of whom served in the Signal Corps, a leather wallet, a small printed Army of Northern Virginia battle flag, an issue of The New South published out of Port Royal, SC, and Morse's Civil War-era Lemaire field glasses. A substantial archive which highlights the critical role of the US Signal Corps during the war. Archive is also significant for its descriptions of the newly emancipated African-Americans inhabiting the Sea Islands, particularly members of the Gullah community, and for the perspective offered by Morse on the "Port Royal Experiment." Other notable content includes references to President Lincoln, Clara Barton, the Battle of Pocotaligo, the Battle of Fort Wagner, the Siege of Charleston Harbor, the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, and the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox.

John Merritt Morse enlisted on 8/13/1862 as a private and mustered into "I" Co. NH 3rd Infantry. After enlistment Morse joined his regiment on the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina. HDS records indicate that he transferred to the US Army Signal Corps on 11/3/1863, however, his letters indicate that he was detached from his command and given duty in the USSC as early as February 1863, a month before the US Signal Corps was officially established as a branch of the US Army. Morse served at various signal stations in the Sea Islands and in Florida prior to joining the X Corps Army of the James in Virginia during the Spring of 1864. After a 30 day furlough in December 1864, Morse would return to field service in Virginia with the XXIV Corps and remain there through the end of the war. Throughout his enlistment Morse was an unwavering correspondent writing detailed and articulate letters describing his circumstances. The majority of letters were written to his wife, Harriet "Hattie" Lord Morse (1838-1892).

While encamped at Hilton Head members of the 3rd NH regiment were experiencing firsthand one of the most significant non-military developments of the war, ie. early encounters between freed enslaved people and Union soldiers at a time before the Emancipation Proclamation and when it was yet unknown if the Union would prevail. Morse was the son of a Free Will Baptist Church minister, and his letters indicate that by April 1863 he was acting as a self-styled minister to a "congregation" of freedmen and women on the island. Morse held regular prayer meetings which he describes in his letters. It is from this ministry that Morse developed amicable relations with the freedmen which allowed him to bear witness to their lives and culture. Morse writes with genuine compassion for the African Americans he encounters, though at times his reflections are laced with a condescension and racism that was typical of the period. Noteworthy in Morse's letters are his observations of how other "ministers" from the North interact with the freedmen. It is likely the ministers referenced by Morse were northern abolitionists who arrived on the Sea Islands as part of the "Port Royal Experiment." Writing from Braddock's Point on April 26, 1863, Morse describes for Hattie one incident which characterized for him the ineptitude and lack of understanding often displayed by northerners who worked with newly freed African Americans: "A minister came here last year from the North to labor among the contrabands on this Island, staid here a few months and left with and promulgated the impression that the Blacks had no Sense and could not learned anything. It is true and a man of education and common sense ought to know that they could not be expected to comprehend truth or anything else 'logically' presented and dressed and decked out with 'high-flown' 'college phrases.' There is not one half of our own people with their advantages that can do it...The minister that thus left this interesting field of labor was the fool and not the contrabands." Morse also details the corruption of government agents on the island who he describes as "hypocritical knaves," and the sometimes cruel and typically discriminatory treatment of freedmen by the Union soldiers who occupied the islands.

Also noteworthy in Morse's letters from the Sea Islands are his descriptions of the unique African American community and culture, as in his June 14, 1863, letter describing the funeral service of a young African American child. Morse writes, in small part: "...The [child's] father's name is Harry, was his master's Coachman and is quite intelligent. He is now a Soldier but came home a week ago not well himself. His wife has had not only the care of her children, but the care of the crop. This morn a man came up and told me the child was dead and that the parents and 'father Cuffee' [freedman minister] wished me to be present and assist in its burial this eve....The corpse was simply shrouded in a plain white shirt with a napkin over the face and placed in a rough coffin. When ready for the Service it was removed to the street in front of the House. Seats arranged around so to form a square....Then sang part of the hymn - 'why do we mourn departed friends.' Then those who wishes viewed the corpse, the lid was nailed down. Three men took the coffin on their shoulders and bore it toward the grave slowly followed by the people in procession chanting a wild and mournful dirge of their own...."

Morse regularly references specific African Americans by name, often with reference to their previous state of bondage and with a name of the enslaver. Morse's letters describe not just the harsh conditions experienced under slavery, but the extreme difficulties faced by African Americans as they adjusted to freedom after so many years in bondage. Additional subject matter includes an African American community celebration in commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation, race relations including the many "yellow" women and children sired by masters and soldiers, the conscription of freedmen by Union soldiers from African American regiments, and much more.

Morse's service with the Signal Corps and military conditions in the Sea Islands are likewise described in these lengthy letters. Folly, Hilton Head, Edisto, Seabrook, and St. Helena Islands are just some of the Signal Corps locations mentioned, and Union army activity near Charleston, Savannah, and Jacksonville (FL) is also referenced. On Oct 11, 1863, Morse writes: "The line from here to Morris and Folly Islands will be open tomorrow or next day. The first station from here [Hilton Head] is at St. Helena village 12 miles distant and will be 130 feet high. There will be three stations in the Reb territory...The work will be hard enough anywhere on the line for we shall have to use 6 foot flags with 12-16 feet of pole and a very strict watch is to be kept." Throughout his letters, Morse describes utilization of both the flag signaling system and the telegraph network, as well as reconnoitering and establishing stations. Morse often describes conditions at the stations, when lines begin opening, how many Signal Corps soldiers are manning the posts, shift times and lengths, names of the other Signal Corps soldiers with him at a station, and the occasional infraction of duty.

After Morse is transferred to duty in Virginia, the intensity of his letters and of his combat experience increases. In a May 1864 letter to Hattie written from the field after joining the X Army Corps on its advance towards Ft. Darling, Morse writes: "...had a rough time getting there [to the front] anyway but finally reached there bout 11 o'clk P.M. and went on duty Rebs charged on our lines 3 times and after one o'clock fighting continued without cessation until Sunday eve. Sunday and until the retreat yesterday about 9 o'clk A.M. we occupied the work which our old Regt. [3rd NH] took in the charge I mentioned. Were in com[munication] with Genl. Smith on the right and with Genl. Gilmore whose HdQtrs were between us and Genl. Smith but in a hollow. We were on a high hill could see most entire length of our lines and part of the Reb. Had view of Battery and R.R. Our position was on the extreme left which gave us a cross view of both our and the Reb lines and works only when hidden by woods." Months later the conditions have become even more dangerous. One week after the Battle of Fair Oaks & Darby Town Road (Oct 27-28, 1864), Morse writes from the X Army Corps HQ "Before Richmond Va" telling Hattie: "...no rest hardly night or day for more than a week. Last two days have been at work building Station by which to open communication between these H'd Qtrs and front and right of our line. Our Station is only 16 ft. high. have a detail of 100 men yesterday and today cutting through woods so we could see to old Station on Newmarket Road...Week ago today and night was on the battlefield...It was the toughest expedition for [?] I have ever been out on and part of the time was exposed to terribel [sic] cross fire from three of the enemies Batteries and wholly unprotected...We commenced skirmishing with the enemy soon after daylight and drove them inch by inch through 'White Oak Swamp' to their outer line of works. After noon we went about mile and half to right and rear and opened com[munication] with Genl. Terry. had no cavalry and were obliged to be our own orderlies. Worked Station and carried our messages to Genl. H all night and next day until noon when we returned to old position inside entrenchments. I guess it was the biggest 'reconoisance' that ever took place...."...

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Exceptional Civil War Archive of John Merritt Morse, NH 3rd Infantry and US Army Signal Corps

Lot of approximately 145 letters, most 4-8pp (1000+ pp total correspondence), many with original covers, spanning Oct 1862 - June 1865. All but approximately 5 letters written by John Merritt Morse (1832-1913) of Jefferson, NH to his family while serving with the NH 3rd Infantry and later the United States Army Signal Corps. Lot also includes 11 portrait CDVs of identified soldiers, many of whom served in the Signal Corps, a leather wallet, a small printed Army of Northern Virginia battle flag, an issue of The New South published out of Port Royal, SC, and Morse's Civil War-era Lemaire field glasses. A substantial archive which highlights the critical role of the US Signal Corps during the war. Archive is also significant for its descriptions of the newly emancipated African-Americans inhabiting the Sea Islands, particularly members of the Gullah community, and for the perspective offered by Morse on the "Port Royal Experiment." Other notable content includes references to President Lincoln, Clara Barton, the Battle of Pocotaligo, the Battle of Fort Wagner, the Siege of Charleston Harbor, the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, and the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox.

John Merritt Morse enlisted on 8/13/1862 as a private and mustered into "I" Co. NH 3rd Infantry. After enlistment Morse joined his regiment on the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina. HDS records indicate that he transferred to the US Army Signal Corps on 11/3/1863, however, his letters indicate that he was detached from his command and given duty in the USSC as early as February 1863, a month before the US Signal Corps was officially established as a branch of the US Army. Morse served at various signal stations in the Sea Islands and in Florida prior to joining the X Corps Army of the James in Virginia during the Spring of 1864. After a 30 day furlough in December 1864, Morse would return to field service in Virginia with the XXIV Corps and remain there through the end of the war. Throughout his enlistment Morse was an unwavering correspondent writing detailed and articulate letters describing his circumstances. The majority of letters were written to his wife, Harriet "Hattie" Lord Morse (1838-1892).

While encamped at Hilton Head members of the 3rd NH regiment were experiencing firsthand one of the most significant non-military developments of the war, ie. early encounters between freed enslaved people and Union soldiers at a time before the Emancipation Proclamation and when it was yet unknown if the Union would prevail. Morse was the son of a Free Will Baptist Church minister, and his letters indicate that by April 1863 he was acting as a self-styled minister to a "congregation" of freedmen and women on the island. Morse held regular prayer meetings which he describes in his letters. It is from this ministry that Morse developed amicable relations with the freedmen which allowed him to bear witness to their lives and culture. Morse writes with genuine compassion for the African Americans he encounters, though at times his reflections are laced with a condescension and racism that was typical of the period. Noteworthy in Morse's letters are his observations of how other "ministers" from the North interact with the freedmen. It is likely the ministers referenced by Morse were northern abolitionists who arrived on the Sea Islands as part of the "Port Royal Experiment." Writing from Braddock's Point on April 26, 1863, Morse describes for Hattie one incident which characterized for him the ineptitude and lack of understanding often displayed by northerners who worked with newly freed African Americans: "A minister came here last year from the North to labor among the contrabands on this Island, staid here a few months and left with and promulgated the impression that the Blacks had no Sense and could not learned anything. It is true and a man of education and common sense ought to know that they could not be expected to comprehend truth or anything else 'logically' presented and dressed and decked out with 'high-flown' 'college phrases.' There is not one half of our own people with their advantages that can do it...The minister that thus left this interesting field of labor was the fool and not the contrabands." Morse also details the corruption of government agents on the island who he describes as "hypocritical knaves," and the sometimes cruel and typically discriminatory treatment of freedmen by the Union soldiers who occupied the islands.

Also noteworthy in Morse's letters from the Sea Islands are his descriptions of the unique African American community and culture, as in his June 14, 1863, letter describing the funeral service of a young African American child. Morse writes, in small part: "...The [child's] father's name is Harry, was his master's Coachman and is quite intelligent. He is now a Soldier but came home a week ago not well himself. His wife has had not only the care of her children, but the care of the crop. This morn a man came up and told me the child was dead and that the parents and 'father Cuffee' [freedman minister] wished me to be present and assist in its burial this eve....The corpse was simply shrouded in a plain white shirt with a napkin over the face and placed in a rough coffin. When ready for the Service it was removed to the street in front of the House. Seats arranged around so to form a square....Then sang part of the hymn - 'why do we mourn departed friends.' Then those who wishes viewed the corpse, the lid was nailed down. Three men took the coffin on their shoulders and bore it toward the grave slowly followed by the people in procession chanting a wild and mournful dirge of their own...."

Morse regularly references specific African Americans by name, often with reference to their previous state of bondage and with a name of the enslaver. Morse's letters describe not just the harsh conditions experienced under slavery, but the extreme difficulties faced by African Americans as they adjusted to freedom after so many years in bondage. Additional subject matter includes an African American community celebration in commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation, race relations including the many "yellow" women and children sired by masters and soldiers, the conscription of freedmen by Union soldiers from African American regiments, and much more.

Morse's service with the Signal Corps and military conditions in the Sea Islands are likewise described in these lengthy letters. Folly, Hilton Head, Edisto, Seabrook, and St. Helena Islands are just some of the Signal Corps locations mentioned, and Union army activity near Charleston, Savannah, and Jacksonville (FL) is also referenced. On Oct 11, 1863, Morse writes: "The line from here to Morris and Folly Islands will be open tomorrow or next day. The first station from here [Hilton Head] is at St. Helena village 12 miles distant and will be 130 feet high. There will be three stations in the Reb territory...The work will be hard enough anywhere on the line for we shall have to use 6 foot flags with 12-16 feet of pole and a very strict watch is to be kept." Throughout his letters, Morse describes utilization of both the flag signaling system and the telegraph network, as well as reconnoitering and establishing stations. Morse often describes conditions at the stations, when lines begin opening, how many Signal Corps soldiers are manning the posts, shift times and lengths, names of the other Signal Corps soldiers with him at a station, and the occasional infraction of duty.

After Morse is transferred to duty in Virginia, the intensity of his letters and of his combat experience increases. In a May 1864 letter to Hattie written from the field after joining the X Army Corps on its advance towards Ft. Darling, Morse writes: "...had a rough time getting there [to the front] anyway but finally reached there bout 11 o'clk P.M. and went on duty Rebs charged on our lines 3 times and after one o'clock fighting continued without cessation until Sunday eve. Sunday and until the retreat yesterday about 9 o'clk A.M. we occupied the work which our old Regt. [3rd NH] took in the charge I mentioned. Were in com[munication] with Genl. Smith on the right and with Genl. Gilmore whose HdQtrs were between us and Genl. Smith but in a hollow. We were on a high hill could see most entire length of our lines and part of the Reb. Had view of Battery and R.R. Our position was on the extreme left which gave us a cross view of both our and the Reb lines and works only when hidden by woods." Months later the conditions have become even more dangerous. One week after the Battle of Fair Oaks & Darby Town Road (Oct 27-28, 1864), Morse writes from the X Army Corps HQ "Before Richmond Va" telling Hattie: "...no rest hardly night or day for more than a week. Last two days have been at work building Station by which to open communication between these H'd Qtrs and front and right of our line. Our Station is only 16 ft. high. have a detail of 100 men yesterday and today cutting through woods so we could see to old Station on Newmarket Road...Week ago today and night was on the battlefield...It was the toughest expedition for [?] I have ever been out on and part of the time was exposed to terribel [sic] cross fire from three of the enemies Batteries and wholly unprotected...We commenced skirmishing with the enemy soon after daylight and drove them inch by inch through 'White Oak Swamp' to their outer line of works. After noon we went about mile and half to right and rear and opened com[munication] with Genl. Terry. had no cavalry and were obliged to be our own orderlies. Worked Station and carried our messages to Genl. H all night and next day until noon when we returned to old position inside entrenchments. I guess it was the biggest 'reconoisance' that ever took place...."...