Giorgio de Chirico, (Italian, 1888-1978)

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo

signed and dated 'g. de Chirico 1959' (lower right); signed and inscribed 'Giorgio de Chirico "Vita silente di oggetti su un tavolo."' (verso)

oil on canvas

92 x 138.3cm (36 1/4 x 54 7/16in).

Painted in 1959

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico.

Provenance

Private collection, Rome (acquired directly from the artist, 1960).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, VIII Quadriennale nazionale d'Arte di Roma, 28 December 1959 - 30 April 1960, no. 12.

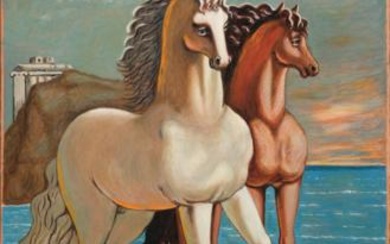

There are few names more intrinsically linked with the history of Italian Modern Art than that of Giorgio de Chirico. His unsettling scenes of town squares, unpopulated except for the odd monumental ancient sculpture or passing train, speak of an intensely Italian consciousness. De Chirico was born in Greece to Italian parents, and was trained in Athens amongst the ruins of the ancient world: a fascination with both mythology and archaeology can be seen as a thread that links his works from the modernity of his first group of paintings shown in Paris in 1913, through to his rejection of Modern Art, and subsequently to his return to classical and Baroque principles.

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo, painted in 1959 and shown at the Rome Quadriennale in the same year, is a monumental piece full of references to both antiquity and the masters of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. A work of impressive size and detail, it marks the culmination of these interests and is one of the most fully realised of de Chirico's vite silenti.

De Chirico had been the toast of Paris in the early years of the First World War, having been picked up by the art dealer Paul Guillaume following a referral from Picasso and Apollinaire. De Chirico's use of classical motifs was already established in these years: The Transformed Dream of 1913 depicts an ancient marble (in this case the head of Jupiter) flanked by a perishing bunch of bananas and two pineapples, in the background the faceless arches of the artist's piazze: the eternal and the temporary. A quintessential juxtaposition of inanimate objects, designed to trigger distant associations and memories.

The idea of imbuing objects such as classical sculptures, mannequins and fruit with intense meaning was central to de Chirico's pittura metafisica. His early works rarely featured human subjects, and yet these canvases constructed with the strangest collectives of objects spoke of the very human world of the mind. Just as de Chirico's star was ascending, he famously denounced the principles of Modern Art in an essay for Valori Plastici in 1919: advocating instead what he referred to as the 'Return of Craftsmanship' and lauding early Renaissance painters such as Luca Signorelli, all the while retaining the use of classical motifs. He was seemingly unable to shake the Greco-Latin influence of his descent.

In the present work, however, de Chirico had turned away from the classicism of the 1920s towards the Baroque period. From 1939 onwards the works of Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders had a profound effect on de Chirico the luxurious brushwork and dramatic stage settings of the Baroque masters can be seen in works such as Self-Portrait in the Park in 17th century Costume, where de Chirico self-consciously presents himself in the guise of a Baroque courtier. The same resplendent grandiosity is evident in the present work. The riches on display across the table in Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo bear a striking similarity to the sumptuous compositions of Snyders, a close collaborator of Rubens and a master of the still life.

Ever the theorist, de Chirico was even particular about the nomenclature of his still lifes of the 1940s and '50s: 'In the German and English language 'natura morta' has another name that is far more beautiful and correct. The name is Stilleben and Still Life: 'vita silenziosa' (silent life). It refers to a painting, in fact, which represents the silent life of objects and things, a calm life, without sound or movement, an existence that expresses itself by means of volume, form and plasticity' (G. de Chirico, 'Le Nature morte', in L'Illustrazione Italiana, Milan, 24 May 1942, p. 500). This preference for the more cerebral German and English translation is indicative of de Chirico's approach to still life. Each object had a meaning or memory that it could trigger, and nothing was placed on the canvas without thought.

View it on

Sale price

Time, Location

Auction House

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo

signed and dated 'g. de Chirico 1959' (lower right); signed and inscribed 'Giorgio de Chirico "Vita silente di oggetti su un tavolo."' (verso)

oil on canvas

92 x 138.3cm (36 1/4 x 54 7/16in).

Painted in 1959

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico.

Provenance

Private collection, Rome (acquired directly from the artist, 1960).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, VIII Quadriennale nazionale d'Arte di Roma, 28 December 1959 - 30 April 1960, no. 12.

There are few names more intrinsically linked with the history of Italian Modern Art than that of Giorgio de Chirico. His unsettling scenes of town squares, unpopulated except for the odd monumental ancient sculpture or passing train, speak of an intensely Italian consciousness. De Chirico was born in Greece to Italian parents, and was trained in Athens amongst the ruins of the ancient world: a fascination with both mythology and archaeology can be seen as a thread that links his works from the modernity of his first group of paintings shown in Paris in 1913, through to his rejection of Modern Art, and subsequently to his return to classical and Baroque principles.

Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo, painted in 1959 and shown at the Rome Quadriennale in the same year, is a monumental piece full of references to both antiquity and the masters of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. A work of impressive size and detail, it marks the culmination of these interests and is one of the most fully realised of de Chirico's vite silenti.

De Chirico had been the toast of Paris in the early years of the First World War, having been picked up by the art dealer Paul Guillaume following a referral from Picasso and Apollinaire. De Chirico's use of classical motifs was already established in these years: The Transformed Dream of 1913 depicts an ancient marble (in this case the head of Jupiter) flanked by a perishing bunch of bananas and two pineapples, in the background the faceless arches of the artist's piazze: the eternal and the temporary. A quintessential juxtaposition of inanimate objects, designed to trigger distant associations and memories.

The idea of imbuing objects such as classical sculptures, mannequins and fruit with intense meaning was central to de Chirico's pittura metafisica. His early works rarely featured human subjects, and yet these canvases constructed with the strangest collectives of objects spoke of the very human world of the mind. Just as de Chirico's star was ascending, he famously denounced the principles of Modern Art in an essay for Valori Plastici in 1919: advocating instead what he referred to as the 'Return of Craftsmanship' and lauding early Renaissance painters such as Luca Signorelli, all the while retaining the use of classical motifs. He was seemingly unable to shake the Greco-Latin influence of his descent.

In the present work, however, de Chirico had turned away from the classicism of the 1920s towards the Baroque period. From 1939 onwards the works of Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders had a profound effect on de Chirico the luxurious brushwork and dramatic stage settings of the Baroque masters can be seen in works such as Self-Portrait in the Park in 17th century Costume, where de Chirico self-consciously presents himself in the guise of a Baroque courtier. The same resplendent grandiosity is evident in the present work. The riches on display across the table in Vita silente di oggetti su tavolo bear a striking similarity to the sumptuous compositions of Snyders, a close collaborator of Rubens and a master of the still life.

Ever the theorist, de Chirico was even particular about the nomenclature of his still lifes of the 1940s and '50s: 'In the German and English language 'natura morta' has another name that is far more beautiful and correct. The name is Stilleben and Still Life: 'vita silenziosa' (silent life). It refers to a painting, in fact, which represents the silent life of objects and things, a calm life, without sound or movement, an existence that expresses itself by means of volume, form and plasticity' (G. de Chirico, 'Le Nature morte', in L'Illustrazione Italiana, Milan, 24 May 1942, p. 500). This preference for the more cerebral German and English translation is indicative of de Chirico's approach to still life. Each object had a meaning or memory that it could trigger, and nothing was placed on the canvas without thought.

Sale price

Time, Location

Auction House

Similar Items

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO Italy Login

Giorgio de Chirico * Austria Login

Giorgio de Chirico * Austria Login