Giorgio de Chirico, (Italian, 1888-1978)

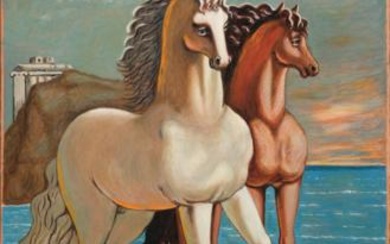

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare

signed 'G. de Chirico' (lower right)

oil on burlap

46 x 55cm (18 1/8 x 21 5/8in).

Painted circa 1934

Provenance

Private collection (acquired directly from the Musée de l'Athénée exhibition, 1934); their sale, Sotheby's, London, 1 December 1982, lot 65.

Private collection, UK (acquired at the above sale).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

Geneva, Musée de l'Athénée, Exposition d'Art Italien, 22 September 18 October 1934, no. 34 (titled 'Chevaux au bord de la mer').

Literature

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, Giorgio de Chirico / Altri enigmi. Opere dal 1914 al 1970, disegni, acquarelli, tempere, progetti per illustrazioni e per incisioni, figurini e scene teatrali, Reggio Emilia, 1983, pl. f (illustrated p. 66, titled 'Cavalli e cavalieri al mare' and incorrectly catalogued as gouache).

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, I bagni misteriosi, de Chirico negli anni Trenta: Parigi, Italia, New York, Milan, 1991, no. 19 (illustrated p. 184, titled 'Dioscuro').

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, Milan, 1995, no. 19 (illustrated p. 184, titled 'Dioscuro').

Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico (eds.), Giorgio de Chirico, catalogo generale - Opere dal 1912 al 1976, Vol. I, Falciano, 2014, no. 123 (illustrated p. 139).

'Giorgio de Chirico, who was born in Greece, no longer needs to paint Pegasus. A horse by the sea with its colour, its eyes and its mouth assumes the importance of a myth' (Jean Cocteau, 1928, quoted in J. de Sanna (ed.) De Chirico And The Mediterranean, New York, 1998, p. 247).

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare, dominated by two muscular horses at the seashore in the shadow of a Grecian temple, immediately recalls the pictorial vocabulary so synonymous with Giorgio de Chirico's post-Metaphysical period. Following his deliberate rupture with modern art with his celebrated article of 1919, 'The Return to Craftsmanship', de Chirico called for a return to traditional subjects and techniques within his art, later developing an iconography which was to be directly inspired by the myth-laden land of his childhood.

Born to Italian parents in the Eastern port of Vólos, de Chirico spent the first eighteen years of his life in Greece. Moving to Athens in 1890, de Chirico's formative years were steeped in the visual history and architecture of this ancient city. He attended the School of Fine Arts at the Athens Polytechnic and recalled in an autobiographical text of 1919 practicing drawing at the age of twelve by copying the ancient statues at Olympia. The Grecian landscape and its archaeological treasures captivated the young artist, prompting a life-long love affair with the imagery of his birthplace: '...all these spectacles of exceptional beauty which I saw in Greece as a boy, and which were the most beautiful I have seen in my life, made a deep impression on me and remained... powerfully impressed on my mind' (G. de Chirico quoted in R. Barber, 'A Roman villa on Greek foundations, Athenian experiences and the imagery of Giorgio de Chirico', in Apollo, October 2002, no. 488, p. 3).

De Chirico's first known paintings from 1908 reveal a penchant for mythology; scenes with sirens, tritons and marine divinities. These mythical yearnings, alongside direct classical motifs, were also present throughout his pittura metafisica, but it was not until the 1920s that the painter began to apply a consistent historicising and Neo-classicism to his work. This transformation was in response to his professed desire in 1919 to be a 'classical painter': 'I lay proud claim to the three words I should like to have as the seal set on each of my works: Pictor classicus sum' (G. de Chirico, 'The Return to Craftsmanship', 1919, quoted in M. Holzhey, De Chirico 1888 1978 The Modern Myth, Cologne, 2005, p. 60). At the same time, the new desire for solidity and equilibrium within his art was congruent with a larger movement known as a 'Rappel à l'ordre'. Developed across Europe in the years following the First World War, this cultural manifestation sought to re-impose a sense of order and plasticity to a world in disarray, offering a visual restorative to the devastated post-war landscape.

De Chirico's new paintings initially explored the techniques and subject matter of the Old Masters from the Italian Renaissance, but from 1922 his style changed and he began to be influenced by the drama of Arnold Böcklin's mid-nineteenth century mythological scenes set within Mediterranean landscapes. Shortly thereafter, de Chirico met Raissa Gurievich, a Russian ballerina who was to become his first wife. In 1925 Gurievich began her studies in archaeology at the Sorbonne, and it was at this moment, as she recalled, that horses in classical settings became a key theme within de Chirico's work: 'The house was full of photographs of the Parthenon, temples and capitals' she explained, 'then Georges started to draw horses with ruins' (R. Gurievich quoted in P. Thea, 'De Chirico and the Disclosure of Myth', in J. de Sanna (ed.), op. cit., p. 37 38). De Chirico's subsequent and almost obsessional depiction of horses in the years that followed was to divide opinion, prompting sneering remarks from some critics who proclaimed that he had recently taken up horse-breeding on an intensive scale (M. Holzhey, op. cit, p. 69 70).

Acting as the archetype which underpinned his varied formal developments, de Chirico would continue to develop the motif of the horse throughout his career. In his 1939 novel Un'Avventura di Monsieur Durdron, the artist describes how the theme of horses allowed him to strive for pictorial quality without being concerned by pictorial innovation. Evolving from tranquil, sculptural beasts, they were later invested with vitality and acquired grandiose flourishes in accordance with his neo-baroque idiom of the 1940s and '50s.

What remained was de Chirico's persistent association of the horse with mythology. A text from 1913, at the beginning of his career, directly makes this association: 'I still think of the enigma of the horse, in the sense of the marine god: once I envisioned it in the gloom of a temple that rose above the sea; the speaking messenger and the seer that the sea god has given to the king of Argos. I imagined it made of cut marble as white and pure as a diamond. It crouched like a sphinx on its haunches and in the movement of its white neck were to be found enigma and infinite nostalgia of the deep' (G. de Chirico quoted in J. de Sanna (ed.), op. cit., p. 246). Thus, while de Chirico's post-metaphysical period tended to reference the classical world and Greek mythology in a more direct way the motif of the horse still looked back to de Chirico's metaphysical journey, namely the quest for the deeper meaning behind the immediate appearance of things. As Cocteau astutely observed, by merely painting a horse on a beach he imbued his work with mythological significance, de Chirico 'no longer needs to paint Pegasus'.

View it on

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare

signed 'G. de Chirico' (lower right)

oil on burlap

46 x 55cm (18 1/8 x 21 5/8in).

Painted circa 1934

Provenance

Private collection (acquired directly from the Musée de l'Athénée exhibition, 1934); their sale, Sotheby's, London, 1 December 1982, lot 65.

Private collection, UK (acquired at the above sale).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

Geneva, Musée de l'Athénée, Exposition d'Art Italien, 22 September 18 October 1934, no. 34 (titled 'Chevaux au bord de la mer').

Literature

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, Giorgio de Chirico / Altri enigmi. Opere dal 1914 al 1970, disegni, acquarelli, tempere, progetti per illustrazioni e per incisioni, figurini e scene teatrali, Reggio Emilia, 1983, pl. f (illustrated p. 66, titled 'Cavalli e cavalieri al mare' and incorrectly catalogued as gouache).

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, I bagni misteriosi, de Chirico negli anni Trenta: Parigi, Italia, New York, Milan, 1991, no. 19 (illustrated p. 184, titled 'Dioscuro').

M. Fagiolo dell'Arco, De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, Milan, 1995, no. 19 (illustrated p. 184, titled 'Dioscuro').

Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico (eds.), Giorgio de Chirico, catalogo generale - Opere dal 1912 al 1976, Vol. I, Falciano, 2014, no. 123 (illustrated p. 139).

'Giorgio de Chirico, who was born in Greece, no longer needs to paint Pegasus. A horse by the sea with its colour, its eyes and its mouth assumes the importance of a myth' (Jean Cocteau, 1928, quoted in J. de Sanna (ed.) De Chirico And The Mediterranean, New York, 1998, p. 247).

Cavalli e cavaliere in riva al mare, dominated by two muscular horses at the seashore in the shadow of a Grecian temple, immediately recalls the pictorial vocabulary so synonymous with Giorgio de Chirico's post-Metaphysical period. Following his deliberate rupture with modern art with his celebrated article of 1919, 'The Return to Craftsmanship', de Chirico called for a return to traditional subjects and techniques within his art, later developing an iconography which was to be directly inspired by the myth-laden land of his childhood.

Born to Italian parents in the Eastern port of Vólos, de Chirico spent the first eighteen years of his life in Greece. Moving to Athens in 1890, de Chirico's formative years were steeped in the visual history and architecture of this ancient city. He attended the School of Fine Arts at the Athens Polytechnic and recalled in an autobiographical text of 1919 practicing drawing at the age of twelve by copying the ancient statues at Olympia. The Grecian landscape and its archaeological treasures captivated the young artist, prompting a life-long love affair with the imagery of his birthplace: '...all these spectacles of exceptional beauty which I saw in Greece as a boy, and which were the most beautiful I have seen in my life, made a deep impression on me and remained... powerfully impressed on my mind' (G. de Chirico quoted in R. Barber, 'A Roman villa on Greek foundations, Athenian experiences and the imagery of Giorgio de Chirico', in Apollo, October 2002, no. 488, p. 3).

De Chirico's first known paintings from 1908 reveal a penchant for mythology; scenes with sirens, tritons and marine divinities. These mythical yearnings, alongside direct classical motifs, were also present throughout his pittura metafisica, but it was not until the 1920s that the painter began to apply a consistent historicising and Neo-classicism to his work. This transformation was in response to his professed desire in 1919 to be a 'classical painter': 'I lay proud claim to the three words I should like to have as the seal set on each of my works: Pictor classicus sum' (G. de Chirico, 'The Return to Craftsmanship', 1919, quoted in M. Holzhey, De Chirico 1888 1978 The Modern Myth, Cologne, 2005, p. 60). At the same time, the new desire for solidity and equilibrium within his art was congruent with a larger movement known as a 'Rappel à l'ordre'. Developed across Europe in the years following the First World War, this cultural manifestation sought to re-impose a sense of order and plasticity to a world in disarray, offering a visual restorative to the devastated post-war landscape.

De Chirico's new paintings initially explored the techniques and subject matter of the Old Masters from the Italian Renaissance, but from 1922 his style changed and he began to be influenced by the drama of Arnold Böcklin's mid-nineteenth century mythological scenes set within Mediterranean landscapes. Shortly thereafter, de Chirico met Raissa Gurievich, a Russian ballerina who was to become his first wife. In 1925 Gurievich began her studies in archaeology at the Sorbonne, and it was at this moment, as she recalled, that horses in classical settings became a key theme within de Chirico's work: 'The house was full of photographs of the Parthenon, temples and capitals' she explained, 'then Georges started to draw horses with ruins' (R. Gurievich quoted in P. Thea, 'De Chirico and the Disclosure of Myth', in J. de Sanna (ed.), op. cit., p. 37 38). De Chirico's subsequent and almost obsessional depiction of horses in the years that followed was to divide opinion, prompting sneering remarks from some critics who proclaimed that he had recently taken up horse-breeding on an intensive scale (M. Holzhey, op. cit, p. 69 70).

Acting as the archetype which underpinned his varied formal developments, de Chirico would continue to develop the motif of the horse throughout his career. In his 1939 novel Un'Avventura di Monsieur Durdron, the artist describes how the theme of horses allowed him to strive for pictorial quality without being concerned by pictorial innovation. Evolving from tranquil, sculptural beasts, they were later invested with vitality and acquired grandiose flourishes in accordance with his neo-baroque idiom of the 1940s and '50s.

What remained was de Chirico's persistent association of the horse with mythology. A text from 1913, at the beginning of his career, directly makes this association: 'I still think of the enigma of the horse, in the sense of the marine god: once I envisioned it in the gloom of a temple that rose above the sea; the speaking messenger and the seer that the sea god has given to the king of Argos. I imagined it made of cut marble as white and pure as a diamond. It crouched like a sphinx on its haunches and in the movement of its white neck were to be found enigma and infinite nostalgia of the deep' (G. de Chirico quoted in J. de Sanna (ed.), op. cit., p. 246). Thus, while de Chirico's post-metaphysical period tended to reference the classical world and Greek mythology in a more direct way the motif of the horse still looked back to de Chirico's metaphysical journey, namely the quest for the deeper meaning behind the immediate appearance of things. As Cocteau astutely observed, by merely painting a horse on a beach he imbued his work with mythological significance, de Chirico 'no longer needs to paint Pegasus'.

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Similar Items

Giorgio de Chirico * Austria Login

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO Italy Login

Giorgio de Chirico * Austria Login