Max Ernst, (German, 1891-1976)

Le Sénégal

Le Sénégal

signed with the artist's initials 'M E' (lower right)

oil on cement, transferred to canvas

124 x 117cm (48 13/16 x 46 1/16in).

Painted in summer 1953

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by Dr. Jürgen Pech.

Provenance

Danie Oven Collection, Paris.

Anon. sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 4 December 1957, lot 82.

Anon. sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 25 May 1959, lot 48.

Galleria Toninelli, Milan.

Private collection, Milan (acquired from the above, circa 1966).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

New York, Lawrence Rubin Greenberg Van Doren Fine Art, Max Ernst, Paintings & Collages from the 1920s - 70s from a Private European Collection, 1 - 26 February 2000, no. 16.

Literature

W. Spies, S. & G. Metken, Max Ernst, Werke 1939 - 1953, Cologne, 1987, no. 3035 (illustrated p. 368).

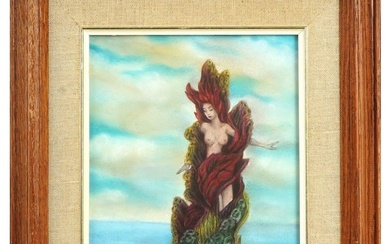

Le Sénégal was painted at a time of huge change for Max Ernst, as he tentatively returned to post-war Europe after a twelve year exile in America. This powerful composition shows strong influences from his time amongst Native Americans in the Sedona desert and recalls some of the artist's earliest ethnological interests.

The present work depicts a mysterious totemic figure, floating untethered within a hazy background. Several insect-like faces peer at us, while the torso of the creature resembles a large, stylised hieroglyphic eye. The sandy ground echoes the desert of Ernst's Arizona home, a memory reinforced by the earthy tones of ochre, yellow, salmon and red. The soft sfumato edges of the figure contrast beautifully to the sharply delicate tracery created by the artist's scratching-out along its contours, whilst its symmetry reminds the viewer perhaps of a Rorschach image, alluding to Ernst's early interest in psychiatry.

Like many other members of the Surrealist movement, Ernst had long been interested in Native American art, whose masks 'seemed to have anticipated their own artistic vision. These austere visages, divided into brilliant colour fields, oscillated between animal and human; some were hinged, opening out to reveal a human face, sometimes even a third creature, behind a bird's head with long beak. Such biomorphic hybrids and their capacity for metamorphosis were as congenial to the Surrealist philosophy as their composite, collage-like character was to the formal concerns of the movement' (S. Metken, 'Ten Thousand Redskins', in W. Spies, (ed.), Max Ernst - A Retrospective, Munich, 1991, p. 357). Such biomorphic references can surely be glimpsed in Le Sénégal whose subject hovers uneasily between human, animal, mask, insect and bird, recalling Ernst's alter ego, Loplop, 'Superior of the Birds'. Emerging from a series of works focussing on birds in the 1920s, the character apparently stemmed from the artist's childhood memory of his pet cockatoo dying a few minutes before his baby sister was born, resulting in a confusion between birds and humans in both his imagination and art. Pertinent to the current work is Ian Turpin's claim that 'in Ernst's fabricated psychobiography, Loplop takes the position of totem, something Ernst describes as a 'private phantom', an animal familiar' (I. Turpin, Max Ernst, London, 1979, p. 88).

Having fled internment in France for the refuge of the United States in 1941, Ernst's interest in the spiritual and tribal continued. He frequented the Museum of Natural History and the Museum of American Indians in New York, and along with his fellow exiled Surrealists discovered a shop owned by a German immigrant specialising in Indian art objects, at which: '[he] did not even baulk at acquiring a six-metre-tall Kwakiutl housepole representing the giant, heavy-breasted Dzonokwa, a cannibal spirit who emerged from the depths of the forest to kidnap children and eat them alive. The monstrous goddess was to stand watch over the artist's house in Sedona until his final return to Europe in 1956' (S. Metken, op. cit., p. 357).

The artist's son, Jimmy, recalled a trip with his father in the summer of 1941: 'At a tourist trading post in Grand Canyon, he and I found ourselves in the usually closed attic of the building surrounded by a sea of ancient Hopi and Zuni Kachina dolls [...] Max bought just about every one' (J. Ernst quoted in W. Spies, (ed.), Max Ernst: Life and Work, An Autobiographical Collage, London, 2006, pp. 168 - 169). This laid the foundation of Ernst's considerable collection of Kachina dolls, figures carved by the Hopi and Zuni people to act as messengers between the human and spirit world. Their carved, slitted mouths, beaks, snouts and corn-husk hair certainly find echoes in Le Sénégal. The Surrealists' early affinity with such art was recorded in the October 1927 journal La Révolution Surréaliste, in which Kachina figures were illustrated, and Ernst's pet dog in Arizona was even named 'Kachina'.

During the disintegration of Ernst's marriage to Peggy Guggenheim, with whom he had immigrated to New York, he became involved with fellow artist Dorothea Tanning and travelled with her to Arizona in 1943. The couple were so captivated by the Sedona desert that they returned there in 1946 to build their own house and studio. The happy years spent in Arizona were undoubtedly integral to the present work, cementing the artist's keen interest in Native American art and culture. Having fled persecution and imprisonment in Europe for his art (twenty-five of his works had been seized from public collections by the Nazis and four were shown in the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich), John Russell ascribes to Ernst a more personal connection with the tribe he befriended on a reservation eighty miles to the north-east of his home: 'Few things in the US are more moving, to a European, than the tenacity of the Hopi Indians in holding fast to their individuality in the face of all money can offer or society invent for its dilapidation' (J. Russell, Max Ernst: Life and Work, London, 1967, p. 140).

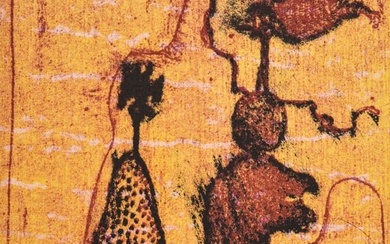

Dorothea Tanning recalled excursions to caves to explore rock paintings and engraved drawings, which appear to have informed Ernst's work at the time; for example, a small gouache from 1946 - 1947, Deux peaux rouges s'apprêtent à danser (sold at Bonhams in February 2016) bears a striking resemblance to an engraving found at the Petroglyph State Park near Albuquerque in New Mexico. In a neat parallel, the present composition was originally painted on the wall of a Paris bistro, the Tour d'Ivoire. The cement ground gives the work the tactility characteristic of Ernst's oeuvre, whether achieved through frottage, grattage or by the use of disparate and experimental media.

Just as the cave paintings, mask and figures of the Native Americans were emblematic and ritualistic, rather than figurative or abstract, so the present work defies easy definition. In a poem Dix mille peaux-rouges ('Ten thousand redskins'), Ernst wrote of the Native Americans that 'for them/time exists/suspended' just as the figure of Le Sénégal floats free in time and space. In this regard the present work finds comparison in Le cri de la mouette, painted slightly earlier in the same year. Painted on Ernst's return to Europe in 1953, these works marked a new approach in his art, whereby the paint field 'is almost featureless [...] a gentle all-over flicker of lyrical colour avoids any specific reference to Nature [...] consideration of space, scale, substance and definition do not apply' (J. Russell, ibid., p. 162). No longer enmeshed in the complicated, faceted backgrounds of his preceding works, Le Sénégal stands defiantly alone, contrary to the more conservative tastes of post-war France. Following a brief and unsatisfactory trip to Europe in 1949 the couple had finally returned to France in 1953, but the desert continued to exert its pull: '1953 - 1954. France for a year or two is punctured with desperate returns to Arizona' (D. Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and her World, New York, 2001, p. 204).

The very title of Le Sénégal hints that Max Ernst was looking to cultures beyond that of the Native Americans he encountered in America, and indeed his interest in disparate societies was shown in the series of lectures he gave in Honolulu at the University of Hawaii in 1952 on 'Traces of Influence of the so-called Primitive Arts on the Art of our Times', covering tribal art from a number of countries.

In its impressive size and solemnity the current work has the presence of a sculpture or carving, an increasing interest for Ernst in Arizona. Le Sénégal looks back to the bas-reliefs with which the artist decorated their desert home; itself an homage to Ernst's earlier house with Leonora Carrington in Saint-Martin d'Ardèche, adorned with murals and tribal figures. The masks, heads and animals Ernst moulded out of cement have been likened by Uwe M. Schneede to the 'skull rack of the rain god Tlaloc at Calixtlahuaca' (U. M. Schneede, The Essential Max Ernst, London, 1972, p. 187). Ernst's largest sculpture, the life-size Capricorne, was created in Sedona in 1948 and recalls certain elements of ancient Egyptian sculpture in the King's Pharaoh-like animal head and rigid pose, finding an echo in the regal figure of Le Sénégal.

Links to Senegal itself in Ernst's life are fleeting but present, first appearing in the record of Ernst's wartime escape in 1940 on the so-called 'ghost train': alleged to be in contact with the enemy, he had been interred in a prisoner camp in Aix-en-Provence. The Camp Commander placed all those prisoners whose lives were in danger from the approaching Nazis on a train, originally bound for Marseille. The 2,500 passengers had hitherto been more lightly guarded: 'their guards up to then, decent inhabitants of the territory, were replaced by Senegalese, who made a rather dubious impression on them' (W. Spies, (ed.), op. cit., p. 154).

Ernst was also a friend and supporter of Léopold Sédar Senghor, a poet and politician who would become the first President of the...

View it on

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

Le Sénégal

Le Sénégal

signed with the artist's initials 'M E' (lower right)

oil on cement, transferred to canvas

124 x 117cm (48 13/16 x 46 1/16in).

Painted in summer 1953

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by Dr. Jürgen Pech.

Provenance

Danie Oven Collection, Paris.

Anon. sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 4 December 1957, lot 82.

Anon. sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 25 May 1959, lot 48.

Galleria Toninelli, Milan.

Private collection, Milan (acquired from the above, circa 1966).

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Exhibited

New York, Lawrence Rubin Greenberg Van Doren Fine Art, Max Ernst, Paintings & Collages from the 1920s - 70s from a Private European Collection, 1 - 26 February 2000, no. 16.

Literature

W. Spies, S. & G. Metken, Max Ernst, Werke 1939 - 1953, Cologne, 1987, no. 3035 (illustrated p. 368).

Le Sénégal was painted at a time of huge change for Max Ernst, as he tentatively returned to post-war Europe after a twelve year exile in America. This powerful composition shows strong influences from his time amongst Native Americans in the Sedona desert and recalls some of the artist's earliest ethnological interests.

The present work depicts a mysterious totemic figure, floating untethered within a hazy background. Several insect-like faces peer at us, while the torso of the creature resembles a large, stylised hieroglyphic eye. The sandy ground echoes the desert of Ernst's Arizona home, a memory reinforced by the earthy tones of ochre, yellow, salmon and red. The soft sfumato edges of the figure contrast beautifully to the sharply delicate tracery created by the artist's scratching-out along its contours, whilst its symmetry reminds the viewer perhaps of a Rorschach image, alluding to Ernst's early interest in psychiatry.

Like many other members of the Surrealist movement, Ernst had long been interested in Native American art, whose masks 'seemed to have anticipated their own artistic vision. These austere visages, divided into brilliant colour fields, oscillated between animal and human; some were hinged, opening out to reveal a human face, sometimes even a third creature, behind a bird's head with long beak. Such biomorphic hybrids and their capacity for metamorphosis were as congenial to the Surrealist philosophy as their composite, collage-like character was to the formal concerns of the movement' (S. Metken, 'Ten Thousand Redskins', in W. Spies, (ed.), Max Ernst - A Retrospective, Munich, 1991, p. 357). Such biomorphic references can surely be glimpsed in Le Sénégal whose subject hovers uneasily between human, animal, mask, insect and bird, recalling Ernst's alter ego, Loplop, 'Superior of the Birds'. Emerging from a series of works focussing on birds in the 1920s, the character apparently stemmed from the artist's childhood memory of his pet cockatoo dying a few minutes before his baby sister was born, resulting in a confusion between birds and humans in both his imagination and art. Pertinent to the current work is Ian Turpin's claim that 'in Ernst's fabricated psychobiography, Loplop takes the position of totem, something Ernst describes as a 'private phantom', an animal familiar' (I. Turpin, Max Ernst, London, 1979, p. 88).

Having fled internment in France for the refuge of the United States in 1941, Ernst's interest in the spiritual and tribal continued. He frequented the Museum of Natural History and the Museum of American Indians in New York, and along with his fellow exiled Surrealists discovered a shop owned by a German immigrant specialising in Indian art objects, at which: '[he] did not even baulk at acquiring a six-metre-tall Kwakiutl housepole representing the giant, heavy-breasted Dzonokwa, a cannibal spirit who emerged from the depths of the forest to kidnap children and eat them alive. The monstrous goddess was to stand watch over the artist's house in Sedona until his final return to Europe in 1956' (S. Metken, op. cit., p. 357).

The artist's son, Jimmy, recalled a trip with his father in the summer of 1941: 'At a tourist trading post in Grand Canyon, he and I found ourselves in the usually closed attic of the building surrounded by a sea of ancient Hopi and Zuni Kachina dolls [...] Max bought just about every one' (J. Ernst quoted in W. Spies, (ed.), Max Ernst: Life and Work, An Autobiographical Collage, London, 2006, pp. 168 - 169). This laid the foundation of Ernst's considerable collection of Kachina dolls, figures carved by the Hopi and Zuni people to act as messengers between the human and spirit world. Their carved, slitted mouths, beaks, snouts and corn-husk hair certainly find echoes in Le Sénégal. The Surrealists' early affinity with such art was recorded in the October 1927 journal La Révolution Surréaliste, in which Kachina figures were illustrated, and Ernst's pet dog in Arizona was even named 'Kachina'.

During the disintegration of Ernst's marriage to Peggy Guggenheim, with whom he had immigrated to New York, he became involved with fellow artist Dorothea Tanning and travelled with her to Arizona in 1943. The couple were so captivated by the Sedona desert that they returned there in 1946 to build their own house and studio. The happy years spent in Arizona were undoubtedly integral to the present work, cementing the artist's keen interest in Native American art and culture. Having fled persecution and imprisonment in Europe for his art (twenty-five of his works had been seized from public collections by the Nazis and four were shown in the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich), John Russell ascribes to Ernst a more personal connection with the tribe he befriended on a reservation eighty miles to the north-east of his home: 'Few things in the US are more moving, to a European, than the tenacity of the Hopi Indians in holding fast to their individuality in the face of all money can offer or society invent for its dilapidation' (J. Russell, Max Ernst: Life and Work, London, 1967, p. 140).

Dorothea Tanning recalled excursions to caves to explore rock paintings and engraved drawings, which appear to have informed Ernst's work at the time; for example, a small gouache from 1946 - 1947, Deux peaux rouges s'apprêtent à danser (sold at Bonhams in February 2016) bears a striking resemblance to an engraving found at the Petroglyph State Park near Albuquerque in New Mexico. In a neat parallel, the present composition was originally painted on the wall of a Paris bistro, the Tour d'Ivoire. The cement ground gives the work the tactility characteristic of Ernst's oeuvre, whether achieved through frottage, grattage or by the use of disparate and experimental media.

Just as the cave paintings, mask and figures of the Native Americans were emblematic and ritualistic, rather than figurative or abstract, so the present work defies easy definition. In a poem Dix mille peaux-rouges ('Ten thousand redskins'), Ernst wrote of the Native Americans that 'for them/time exists/suspended' just as the figure of Le Sénégal floats free in time and space. In this regard the present work finds comparison in Le cri de la mouette, painted slightly earlier in the same year. Painted on Ernst's return to Europe in 1953, these works marked a new approach in his art, whereby the paint field 'is almost featureless [...] a gentle all-over flicker of lyrical colour avoids any specific reference to Nature [...] consideration of space, scale, substance and definition do not apply' (J. Russell, ibid., p. 162). No longer enmeshed in the complicated, faceted backgrounds of his preceding works, Le Sénégal stands defiantly alone, contrary to the more conservative tastes of post-war France. Following a brief and unsatisfactory trip to Europe in 1949 the couple had finally returned to France in 1953, but the desert continued to exert its pull: '1953 - 1954. France for a year or two is punctured with desperate returns to Arizona' (D. Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and her World, New York, 2001, p. 204).

The very title of Le Sénégal hints that Max Ernst was looking to cultures beyond that of the Native Americans he encountered in America, and indeed his interest in disparate societies was shown in the series of lectures he gave in Honolulu at the University of Hawaii in 1952 on 'Traces of Influence of the so-called Primitive Arts on the Art of our Times', covering tribal art from a number of countries.

In its impressive size and solemnity the current work has the presence of a sculpture or carving, an increasing interest for Ernst in Arizona. Le Sénégal looks back to the bas-reliefs with which the artist decorated their desert home; itself an homage to Ernst's earlier house with Leonora Carrington in Saint-Martin d'Ardèche, adorned with murals and tribal figures. The masks, heads and animals Ernst moulded out of cement have been likened by Uwe M. Schneede to the 'skull rack of the rain god Tlaloc at Calixtlahuaca' (U. M. Schneede, The Essential Max Ernst, London, 1972, p. 187). Ernst's largest sculpture, the life-size Capricorne, was created in Sedona in 1948 and recalls certain elements of ancient Egyptian sculpture in the King's Pharaoh-like animal head and rigid pose, finding an echo in the regal figure of Le Sénégal.

Links to Senegal itself in Ernst's life are fleeting but present, first appearing in the record of Ernst's wartime escape in 1940 on the so-called 'ghost train': alleged to be in contact with the enemy, he had been interred in a prisoner camp in Aix-en-Provence. The Camp Commander placed all those prisoners whose lives were in danger from the approaching Nazis on a train, originally bound for Marseille. The 2,500 passengers had hitherto been more lightly guarded: 'their guards up to then, decent inhabitants of the territory, were replaced by Senegalese, who made a rather dubious impression on them' (W. Spies, (ed.), op. cit., p. 154).

Ernst was also a friend and supporter of Léopold Sédar Senghor, a poet and politician who would become the first President of the...