The Bedford Master (active first half 15th century)

The Bedford Master (active first half 15th century)

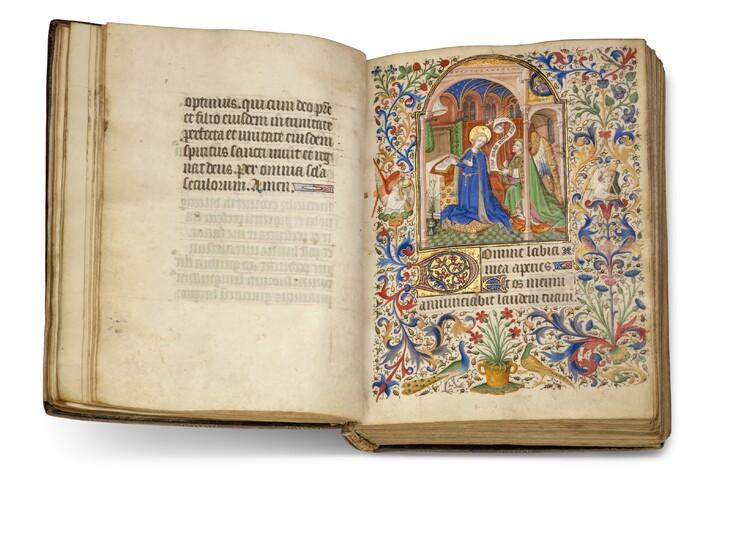

The Hours of Anne de Neufville, use of Paris, in Latin and French, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Paris, c.1430]

A treasure of gold and rich colours that demonstrates the technical refinement and devotional sensitivity of the Bedford Master, the last representative of the great age of Parisian illumination fostered by the Duke of Berry, in a superb 16th-century fanfare binding.

165 x 124mm. ii + 215 (last as pastedown), complete, collation: 112, 2-268, 273(?of 4, iv a cancelled blank), 13 lines ruled in red, ruled space: 89 x 63mm, one-line initials in gold on divided grounds of pink and blue, numerous two-line initials in pink and blue on gold grounds with foliate infills with border to left margin of fine gold leaves with small flowers and fruit in red and blue on hairline tendrils, similar three-line initials with similar borders to both vertical margins, 15 miniatures in full borders of acanthus stems linking fruit and flowers with small gold discs, some with angels, birds, butterflies or pots of flowers.

Binding: 16th-century brown morocco gilt tooled à la fanfare, framed with triple fillet, a central oval compartment linked to four oval and four rectangular compartments, with roundels or part-roundels at the frame, all filled with varying combinations of flower and fruit motifs and angel heads, surrounded by spirals and branches of meticulously veined leaves, in the central oval on upper cover ANN’/EN VEV/FIDEL/LE, in central oval on lower cover VNE/NÉ’ A/VN FI=/DELLE, spine smooth and similarly tooled (lacking two tie fasteners). Some of the same tools were apparently used on the five volumes remaining of a six-volume edition of Plutarch, Paris, Michel de Vascosan, 1574, bound for presentation to Charles IX who died that year (Paris, BnF, RES-J-3248 – RES-J-3250, RES-J-3252, RES-J-3253). They apparently recur with the angel heads on a binding executed for Jacques-Auguste de Thou before his marriage in 1587 and dated to c.1575, Liber psalmorum Davidis, Annotationes [...]. Paris, Robert Estienne, 1546 (Wittock Collection, no 60, A. Hobson and Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th-century Bookbindings, Biblioteca Wittockiana, 1991; Christie’s, Paris, 7 October 2005, lot 42). These splendid fanfare bindings are difficult to attribute to a distinct atelier: they seem the work of a small group of exceptionally talented Parisian binders, active from c.1575 to c.1585, who worked to similar patterns. The Charles IX bindings support a date c.1575 for the closely related de Neufville and de Thou bindings, at the beginning of the group’s activity.

Content:

Calendar including St Genevieve (3 January and 26 November), ff.1-12; Gospel extracts, each followed by a prayer ff.13-24; Obsecro te in masculine and then feminine for michi N famule tue ff.21-25v; O intemerata in feminine ff. 25v-28v; Hours of the Virgin, use of Paris ff.29-100v; Penitential Psalms ff.101-117v; litany including Marcel, Fiacre, Genevieve and Avia, as well as Firmin and Fuscian, specially revered in Amiens and Lambert, Bishop of Maastricht-Liège ff.117v-127v; Hours of the Cross ff.128-138; Hours of the Holy Spirit ff.138v-147; short Office of the Dead ff.147v-186; Quinze joies ff.186v-193v; Cinq plaies ff.194-198; Memorials ff.198-213: Sts Michael f.198, John the Baptist f.198v, Peter and Paul f.199, Christopher (in masculine) f.200, Nicholas f.201, Anthony Abbot f.202, Claude f.203, Eutropius f.203v, Catherine f.204v, Margaret f.205, Genevieve f.205v, Ave verum corpus f.206v, Joachim and Anna f.207, Mary Magdalene f.208, cinq festes de nostre dame f.208v, the Cross f.210, Gervase and Protase f.211, Leonard f.211v, Fiacre f.212v; ruled blanks, last as pastedown ff.214-215.

The book was specially written for the lady shown before St Anthony Abbot, f.202; the scribe began the Obsecro te in the masculine before realising, or remembering, and changing to the feminine, then forgetting again for the prayer to St Christopher. There are a few other mistakes: on f.164v, for instance, a repeated michi has been neatly cancelled in red.

Illumination:

The miniatures are ‘exceedingly fine paintings by the Bedford Master’, to quote John Plummer, their fineness sparklingly fresh in a remarkably well preserved manuscript. One of the most influential French illuminators of the earlier 15th century, the Bedford Master illuminated four books owned or commissioned by John, Duke of Bedford (1389-1435), brother of Henry V of England and Regent in France for the infant Henry VI. He was named from the Bedford Hours, begun c.1405, with main miniatures mostly c.1415, and completed for Bedford after his marriage to Anne of Burgundy in 1423 (London, BL Add. ms 18850), and the Salisbury Breviary, commissioned by him c.1424, worked on until the 1460s and never completed (Paris, BnF ms lat. 17294, coincidentally presented in 1625 to Camille de Neufville-Villeroy [1606-1698], the future Archbishop of Lyons). The Benedictional (so-called Pontifical), commissioned by Bedford and completed after his death, aroused great aesthetic and antiquarian admiration before its destruction in 1871; a small Book of Hours commissioned by, and completed for, Bedford has lost most of its decoration (BL. Add. Ms 74754). While the painterly style and elegant figure types of the Bedford Master are easily recognisable, the complexity of the manuscripts from which he was named means that there is no consensus on the key miniatures to use as a basis for further attributions; the evidence for identifying him with Haincelin de Hagenau, documented in Paris 1403-1415, remains inconclusive. His work was much in demand: he employed assistants and often collaborated with independent illuminators to satisfy patrons ranging from the Duke of Berry to the discerning first owner of the de Neufville Hours, who secured a volume entirely coherent in style (see C. Reynolds, ‘The Workshop of the Master of the Duke of Bedford: Definitions and Identities’, G. Coenen and P. Ainsworth, Patrons Authors and Workshops, Books and Book Production in Paris around 1400, 2006, pp.437-72).

The consistency evident in the most refined and accomplished works in the Bedford style from c.1405 to c.1435 makes it reasonable to attribute them to the Master himself. The de Neufville Hours belongs to this group, with figures less elongated than those in the c.1415 miniatures in the Bedford Hours. As pointed out by Eleanor Spencer when she published the manuscript in The Burlington Magazine in 1977, the de Neufville Hours relates most closely to the Salisbury Breviary (‘The Hours of Anne de Neufville’, vol. CXIX, pp.705-707). The miniatures in the Breviary nearest in style and execution to the de Neufville Hours were painted for the Duke of Bedford and so datable before his death on 14 September 1435, e.g the Institution of the Eucharist with its Old Testament types of Abraham and Melchisedech, adored by the Duke and Duchess of Bedford, f.283v. Other correspondences permit a more precise dating. The composition of the Adoration of the Magi in the de Neufville Hours is the same as that in a small miniature in the Breviary, f.105v, where it is reversed and painted with much less refinement. On the facing recto, f.106, appear the arms of the Duke and his second wife, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, whom he married in 1433.

A date of c.1430 for the de Neufville Hours gains further support from its borders, which are by the same hand as the border with the Duke’s tree root badges around the Institution of Eucharist and the portraits of the Duke and Duchess. Appearing as the second border hand in the Breviary, this illuminator worked with the Bedford Master from its inception in, or soon after, 1424 until the mid-1430s. The border he supplied to the miniature of the Meeting at the Golden Gate, f.386v, lacks any evidence of the devotion of the Duke’s first wife, Anne of Burgundy, to St Anne, and was presumably painted after her death in 1432. In his border on f.387v, which forms a bifolium with f.386, the Duke’s arms were left incomplete, indicating a date in, or close to, 1435.

The richly coloured and gilded motifs of the borders complement the rich colours and gold of the miniatures. The Bedford Master uses gold for itself, in the crowns and gifts of the magi, for instance, and in textiles and embroidered trimmings; it can convey light, in divine radiances and the highlights that enhance his landscapes; symbolise the divine as haloes and suggest the glories of heaven by replacing skies. Reassuringly, gold appears above the cemetery where Michael battles to save a soul and above St Anthony, before whom the owner is immortalised in prayer. The smaller format of the de Neufville miniatures compared to the main miniatures of the Breviary encouraged a concentration on the chief protagonists. This is most evident in the Nativity scenes in both volumes, where the smaller miniature gains from its greater simplicity. Joseph no longer overlaps the Child, leaving the divine sacrificial victim isolated and vulnerable in the manger. The distance between the Son of God and his worshipping mother contrasts with their closeness in the miniature of the Presentation in the Temple of the de Neufville Hours, where Christ in the High Priest’s arms touchingly reaches back towards the Virgin. The familiar scenes are given a human immediacy through such gestures: fleeing to Egypt, the Virgin tenderly protects the child within her mantle.

Every miniature in the de Neufville Hours is an example of the ingenuity of the Bedford Master, whether in its varying and developing existing compositional patterns familiar from the Bedford manuscripts, or in its apparent invention, as with the St Anthony venerated by the owner, f.202, which inspired the St Anthony in the Hours of the comte de Dunois (from which the Bedford Master’s successor, the Dunois Master, is named [BL Yates Thompson 3, f.265v]). The Virgin weaving, as...

View it on

Estimate

Time

Auction House

The Bedford Master (active first half 15th century)

The Hours of Anne de Neufville, use of Paris, in Latin and French, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Paris, c.1430]

A treasure of gold and rich colours that demonstrates the technical refinement and devotional sensitivity of the Bedford Master, the last representative of the great age of Parisian illumination fostered by the Duke of Berry, in a superb 16th-century fanfare binding.

165 x 124mm. ii + 215 (last as pastedown), complete, collation: 112, 2-268, 273(?of 4, iv a cancelled blank), 13 lines ruled in red, ruled space: 89 x 63mm, one-line initials in gold on divided grounds of pink and blue, numerous two-line initials in pink and blue on gold grounds with foliate infills with border to left margin of fine gold leaves with small flowers and fruit in red and blue on hairline tendrils, similar three-line initials with similar borders to both vertical margins, 15 miniatures in full borders of acanthus stems linking fruit and flowers with small gold discs, some with angels, birds, butterflies or pots of flowers.

Binding: 16th-century brown morocco gilt tooled à la fanfare, framed with triple fillet, a central oval compartment linked to four oval and four rectangular compartments, with roundels or part-roundels at the frame, all filled with varying combinations of flower and fruit motifs and angel heads, surrounded by spirals and branches of meticulously veined leaves, in the central oval on upper cover ANN’/EN VEV/FIDEL/LE, in central oval on lower cover VNE/NÉ’ A/VN FI=/DELLE, spine smooth and similarly tooled (lacking two tie fasteners). Some of the same tools were apparently used on the five volumes remaining of a six-volume edition of Plutarch, Paris, Michel de Vascosan, 1574, bound for presentation to Charles IX who died that year (Paris, BnF, RES-J-3248 – RES-J-3250, RES-J-3252, RES-J-3253). They apparently recur with the angel heads on a binding executed for Jacques-Auguste de Thou before his marriage in 1587 and dated to c.1575, Liber psalmorum Davidis, Annotationes [...]. Paris, Robert Estienne, 1546 (Wittock Collection, no 60, A. Hobson and Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th-century Bookbindings, Biblioteca Wittockiana, 1991; Christie’s, Paris, 7 October 2005, lot 42). These splendid fanfare bindings are difficult to attribute to a distinct atelier: they seem the work of a small group of exceptionally talented Parisian binders, active from c.1575 to c.1585, who worked to similar patterns. The Charles IX bindings support a date c.1575 for the closely related de Neufville and de Thou bindings, at the beginning of the group’s activity.

Content:

Calendar including St Genevieve (3 January and 26 November), ff.1-12; Gospel extracts, each followed by a prayer ff.13-24; Obsecro te in masculine and then feminine for michi N famule tue ff.21-25v; O intemerata in feminine ff. 25v-28v; Hours of the Virgin, use of Paris ff.29-100v; Penitential Psalms ff.101-117v; litany including Marcel, Fiacre, Genevieve and Avia, as well as Firmin and Fuscian, specially revered in Amiens and Lambert, Bishop of Maastricht-Liège ff.117v-127v; Hours of the Cross ff.128-138; Hours of the Holy Spirit ff.138v-147; short Office of the Dead ff.147v-186; Quinze joies ff.186v-193v; Cinq plaies ff.194-198; Memorials ff.198-213: Sts Michael f.198, John the Baptist f.198v, Peter and Paul f.199, Christopher (in masculine) f.200, Nicholas f.201, Anthony Abbot f.202, Claude f.203, Eutropius f.203v, Catherine f.204v, Margaret f.205, Genevieve f.205v, Ave verum corpus f.206v, Joachim and Anna f.207, Mary Magdalene f.208, cinq festes de nostre dame f.208v, the Cross f.210, Gervase and Protase f.211, Leonard f.211v, Fiacre f.212v; ruled blanks, last as pastedown ff.214-215.

The book was specially written for the lady shown before St Anthony Abbot, f.202; the scribe began the Obsecro te in the masculine before realising, or remembering, and changing to the feminine, then forgetting again for the prayer to St Christopher. There are a few other mistakes: on f.164v, for instance, a repeated michi has been neatly cancelled in red.

Illumination:

The miniatures are ‘exceedingly fine paintings by the Bedford Master’, to quote John Plummer, their fineness sparklingly fresh in a remarkably well preserved manuscript. One of the most influential French illuminators of the earlier 15th century, the Bedford Master illuminated four books owned or commissioned by John, Duke of Bedford (1389-1435), brother of Henry V of England and Regent in France for the infant Henry VI. He was named from the Bedford Hours, begun c.1405, with main miniatures mostly c.1415, and completed for Bedford after his marriage to Anne of Burgundy in 1423 (London, BL Add. ms 18850), and the Salisbury Breviary, commissioned by him c.1424, worked on until the 1460s and never completed (Paris, BnF ms lat. 17294, coincidentally presented in 1625 to Camille de Neufville-Villeroy [1606-1698], the future Archbishop of Lyons). The Benedictional (so-called Pontifical), commissioned by Bedford and completed after his death, aroused great aesthetic and antiquarian admiration before its destruction in 1871; a small Book of Hours commissioned by, and completed for, Bedford has lost most of its decoration (BL. Add. Ms 74754). While the painterly style and elegant figure types of the Bedford Master are easily recognisable, the complexity of the manuscripts from which he was named means that there is no consensus on the key miniatures to use as a basis for further attributions; the evidence for identifying him with Haincelin de Hagenau, documented in Paris 1403-1415, remains inconclusive. His work was much in demand: he employed assistants and often collaborated with independent illuminators to satisfy patrons ranging from the Duke of Berry to the discerning first owner of the de Neufville Hours, who secured a volume entirely coherent in style (see C. Reynolds, ‘The Workshop of the Master of the Duke of Bedford: Definitions and Identities’, G. Coenen and P. Ainsworth, Patrons Authors and Workshops, Books and Book Production in Paris around 1400, 2006, pp.437-72).

The consistency evident in the most refined and accomplished works in the Bedford style from c.1405 to c.1435 makes it reasonable to attribute them to the Master himself. The de Neufville Hours belongs to this group, with figures less elongated than those in the c.1415 miniatures in the Bedford Hours. As pointed out by Eleanor Spencer when she published the manuscript in The Burlington Magazine in 1977, the de Neufville Hours relates most closely to the Salisbury Breviary (‘The Hours of Anne de Neufville’, vol. CXIX, pp.705-707). The miniatures in the Breviary nearest in style and execution to the de Neufville Hours were painted for the Duke of Bedford and so datable before his death on 14 September 1435, e.g the Institution of the Eucharist with its Old Testament types of Abraham and Melchisedech, adored by the Duke and Duchess of Bedford, f.283v. Other correspondences permit a more precise dating. The composition of the Adoration of the Magi in the de Neufville Hours is the same as that in a small miniature in the Breviary, f.105v, where it is reversed and painted with much less refinement. On the facing recto, f.106, appear the arms of the Duke and his second wife, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, whom he married in 1433.

A date of c.1430 for the de Neufville Hours gains further support from its borders, which are by the same hand as the border with the Duke’s tree root badges around the Institution of Eucharist and the portraits of the Duke and Duchess. Appearing as the second border hand in the Breviary, this illuminator worked with the Bedford Master from its inception in, or soon after, 1424 until the mid-1430s. The border he supplied to the miniature of the Meeting at the Golden Gate, f.386v, lacks any evidence of the devotion of the Duke’s first wife, Anne of Burgundy, to St Anne, and was presumably painted after her death in 1432. In his border on f.387v, which forms a bifolium with f.386, the Duke’s arms were left incomplete, indicating a date in, or close to, 1435.

The richly coloured and gilded motifs of the borders complement the rich colours and gold of the miniatures. The Bedford Master uses gold for itself, in the crowns and gifts of the magi, for instance, and in textiles and embroidered trimmings; it can convey light, in divine radiances and the highlights that enhance his landscapes; symbolise the divine as haloes and suggest the glories of heaven by replacing skies. Reassuringly, gold appears above the cemetery where Michael battles to save a soul and above St Anthony, before whom the owner is immortalised in prayer. The smaller format of the de Neufville miniatures compared to the main miniatures of the Breviary encouraged a concentration on the chief protagonists. This is most evident in the Nativity scenes in both volumes, where the smaller miniature gains from its greater simplicity. Joseph no longer overlaps the Child, leaving the divine sacrificial victim isolated and vulnerable in the manger. The distance between the Son of God and his worshipping mother contrasts with their closeness in the miniature of the Presentation in the Temple of the de Neufville Hours, where Christ in the High Priest’s arms touchingly reaches back towards the Virgin. The familiar scenes are given a human immediacy through such gestures: fleeing to Egypt, the Virgin tenderly protects the child within her mantle.

Every miniature in the de Neufville Hours is an example of the ingenuity of the Bedford Master, whether in its varying and developing existing compositional patterns familiar from the Bedford manuscripts, or in its apparent invention, as with the St Anthony venerated by the owner, f.202, which inspired the St Anthony in the Hours of the comte de Dunois (from which the Bedford Master’s successor, the Dunois Master, is named [BL Yates Thompson 3, f.265v]). The Virgin weaving, as...