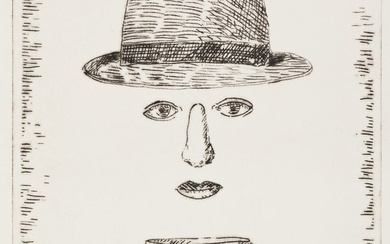

RENÉ MAGRITTE, (1898-1967)

La chambre d'Ecoute

La chambre d'Ecoute

signed 'Magritte' (lower right)

pen and black ink on paper

15.5 x 20.8cm (6 1/8 x 8 3/16in).

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by the Comité Magritte.

Provenance

Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, no. 6701.

Private collection, US (a gift from the above in December 2009).

La chambre d'Ecoute celebrates one of Magritte's most famous motifs, the apple, which was oft repeated in playful yet unsettling compositions. Illustrating the artist's virtuoso draughtsmanship, the present work shows the mature realisation of the artist's iconic style which was first ignited by his meeting key figures from the Surrealist movement in the 1920s.

The twenties were a decade which sculpted the young Belgian into a prominent artist within the Surrealist group and helped carve his name into the annals of modern art history. A defining moment in the lead up to Magritte's visit to Paris in 1927 and involvement with the likes of Salvador Dalí and André Breton was an earlier encounter with Giorgio de Chirico's metaphysical masterpiece The Song of Love, in 1923. It was a profoundly moving experience for the artist, both emotionally and artistically, and the work of de Chirico was hugely influential for not only Magritte, but also a great number of the Surrealist artists. The work's inconsequential objects, its sinister architectural forms, vacuous passageways and a train that flicks past just out of sight, conjures feelings of both the absurd and the ominous.

The presence of absurdity coupled with the quietly disconcerting is a common element of the Surrealist output, although it was by no means of their sole invention. The group had in fact found this common ground within the prose-poem Les Chants de Maldoror (1868-1869) by the Comte de Lautréamont. Having existed in something of obscurity at the time of publishing, this piece of transgressive literature was rediscovered by the Surrealists, who found mutual sentiment in the verse's themes of violence and the absurd. The piece also captured one of the most important principles of the Surrealist aesthetic: to challenge the observer's preconceived and preconditioned perception of reality through the juxtaposition of two entirely foreign realities.

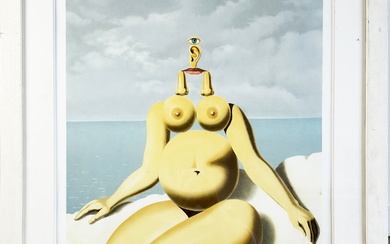

This principle is most evidently revealed in the biomorphic abstraction that was so prevalent with the Surrealists through the late 1920s, in particular in the work of the Joan Miró and Jean (Hans) Arp (see lot 45). From the Greek words for life, 'bios', and form, 'morphe', the abstracted imagery adopted by these artists presented a world of bulbous, enticing, sexually-charged forms that were simultaneously totally alien to the viewer whilst maintaining a presence of uncanny familiarity. In contrast, Magritte's figurative creations challenged the real world through a naturalistic and highly detailed depiction of ordinary objects suspended in everyday settings, juxtaposed in an entirely illogical manner, often transposing the monumental into the seemingly mundane or vice versa: 'In view of my determination to make the most familiar objects scream aloud, these had to be disposed in a new order and to be charged with a vibrant significance' (R. Magritte quoted in P. Waldberg, René Magritte, Brussels, 1965, p. 116).

It is from this methodology that Magritte's use of the motif is so entirely important whilst, in a most satirically Magritte-ian way, remaining utterly irrelevant. His works are characterized by a series of these motifs – apples, curtains, bowler hatted men, birds, objects in flames, and more – which he endlessly arranges and re-arranges within varying settings whilst the viewer struggles to find meaning and theory in his image. His most iconic and successful subjects challenge the viewer. They challenge the viewer to find and define reason, clarity and meaning in the work, to question their idea of what is real and what is not.

In addition to his use of motifs, Magritte used the titles of his works to divert and test the thought process of his viewers, subverting their expectations by assigning descriptions that bore almost no relevance to the depicted scene. In his own words, 'the titles are meant as an extra protection to counter any attempt to reduce poetry to a pointless game' (R. Magritte quoted in D. Sylvester (ed.), René Magritte, catalogue raisonné, Vol. V, Supplément, London, 1997, p. 20).

La chambre d'Ecoute presents the viewer with the iconic, orb-like apple hanging seemingly unaided within a room. Immediately we must question which object is 'real'; is it the apple that is oversized, or is the room extremely small? Of course, our questioning is futile, for the presence of either must discredit the reality of the situation entirely and regardless, the artist has led us into an endless loop of unanswerable uncertainty. Aside from probing the viewer's constructs of reality, Magritte prompts us to question what we are not seeing, to question that which is hidden within. Objects in his works are often partially concealed, as in the 1964 Son of Man, so the viewer can deduce that the apple here may well be concealing something – or indeed nothing at all. It is a somewhat Schrödinger's cat-like situation; the potentially hidden presence is both simultaneously present and absent. It is another characteristic of the quietly ominous.

Whilst it is easy to attribute the playful, potentially Machiavellian nature of this to nothing more than toying with his viewership, a more disturbing explanation for Magritte's use of the everyday object to obscure can be found in his childhood memories of his mentally ill mother. As a young boy he would sit for long periods of time locked in her room until after several attempts she eventually escaped and took her own life in the River Sambre in 1912. The claustrophobic nature of the expanded apple sucking the space from the room in the present work could certainly be linked to this experience, as the artist attempts to eliminate what was once his normality with an alternate reality, leading us also to question what, or who, is hidden behind the apple.

As a study for two seminal paintings from 1952 and 1958 titled La chambre d'écoute, or The Listening Room, the present work sits firmly within Magritte's seminal mature period and its importance as a study for one his most recognisable works cannot be understated, with both finished paintings now residing in public collections in the US and Switzerland.

The nature of Magritte's studies for his paintings offers the viewer an intimate insight into the bubbling mind of this Surrealist master like no other. Whilst the present work appears to be a study for the aforementioned paintings, we are immediately drawn to the highly finished nature of the draughtsmanship and the considered ink line, which, coupled with the artist's signature in the lower right corner, offers an elevated position for the work and almost allows it to be placed within The Listening Room series as a finished work in its own right.

View it on

Sale price

Estimate

Time, Location

Auction House

La chambre d'Ecoute

La chambre d'Ecoute

signed 'Magritte' (lower right)

pen and black ink on paper

15.5 x 20.8cm (6 1/8 x 8 3/16in).

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by the Comité Magritte.

Provenance

Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, no. 6701.

Private collection, US (a gift from the above in December 2009).

La chambre d'Ecoute celebrates one of Magritte's most famous motifs, the apple, which was oft repeated in playful yet unsettling compositions. Illustrating the artist's virtuoso draughtsmanship, the present work shows the mature realisation of the artist's iconic style which was first ignited by his meeting key figures from the Surrealist movement in the 1920s.

The twenties were a decade which sculpted the young Belgian into a prominent artist within the Surrealist group and helped carve his name into the annals of modern art history. A defining moment in the lead up to Magritte's visit to Paris in 1927 and involvement with the likes of Salvador Dalí and André Breton was an earlier encounter with Giorgio de Chirico's metaphysical masterpiece The Song of Love, in 1923. It was a profoundly moving experience for the artist, both emotionally and artistically, and the work of de Chirico was hugely influential for not only Magritte, but also a great number of the Surrealist artists. The work's inconsequential objects, its sinister architectural forms, vacuous passageways and a train that flicks past just out of sight, conjures feelings of both the absurd and the ominous.

The presence of absurdity coupled with the quietly disconcerting is a common element of the Surrealist output, although it was by no means of their sole invention. The group had in fact found this common ground within the prose-poem Les Chants de Maldoror (1868-1869) by the Comte de Lautréamont. Having existed in something of obscurity at the time of publishing, this piece of transgressive literature was rediscovered by the Surrealists, who found mutual sentiment in the verse's themes of violence and the absurd. The piece also captured one of the most important principles of the Surrealist aesthetic: to challenge the observer's preconceived and preconditioned perception of reality through the juxtaposition of two entirely foreign realities.

This principle is most evidently revealed in the biomorphic abstraction that was so prevalent with the Surrealists through the late 1920s, in particular in the work of the Joan Miró and Jean (Hans) Arp (see lot 45). From the Greek words for life, 'bios', and form, 'morphe', the abstracted imagery adopted by these artists presented a world of bulbous, enticing, sexually-charged forms that were simultaneously totally alien to the viewer whilst maintaining a presence of uncanny familiarity. In contrast, Magritte's figurative creations challenged the real world through a naturalistic and highly detailed depiction of ordinary objects suspended in everyday settings, juxtaposed in an entirely illogical manner, often transposing the monumental into the seemingly mundane or vice versa: 'In view of my determination to make the most familiar objects scream aloud, these had to be disposed in a new order and to be charged with a vibrant significance' (R. Magritte quoted in P. Waldberg, René Magritte, Brussels, 1965, p. 116).

It is from this methodology that Magritte's use of the motif is so entirely important whilst, in a most satirically Magritte-ian way, remaining utterly irrelevant. His works are characterized by a series of these motifs – apples, curtains, bowler hatted men, birds, objects in flames, and more – which he endlessly arranges and re-arranges within varying settings whilst the viewer struggles to find meaning and theory in his image. His most iconic and successful subjects challenge the viewer. They challenge the viewer to find and define reason, clarity and meaning in the work, to question their idea of what is real and what is not.

In addition to his use of motifs, Magritte used the titles of his works to divert and test the thought process of his viewers, subverting their expectations by assigning descriptions that bore almost no relevance to the depicted scene. In his own words, 'the titles are meant as an extra protection to counter any attempt to reduce poetry to a pointless game' (R. Magritte quoted in D. Sylvester (ed.), René Magritte, catalogue raisonné, Vol. V, Supplément, London, 1997, p. 20).

La chambre d'Ecoute presents the viewer with the iconic, orb-like apple hanging seemingly unaided within a room. Immediately we must question which object is 'real'; is it the apple that is oversized, or is the room extremely small? Of course, our questioning is futile, for the presence of either must discredit the reality of the situation entirely and regardless, the artist has led us into an endless loop of unanswerable uncertainty. Aside from probing the viewer's constructs of reality, Magritte prompts us to question what we are not seeing, to question that which is hidden within. Objects in his works are often partially concealed, as in the 1964 Son of Man, so the viewer can deduce that the apple here may well be concealing something – or indeed nothing at all. It is a somewhat Schrödinger's cat-like situation; the potentially hidden presence is both simultaneously present and absent. It is another characteristic of the quietly ominous.

Whilst it is easy to attribute the playful, potentially Machiavellian nature of this to nothing more than toying with his viewership, a more disturbing explanation for Magritte's use of the everyday object to obscure can be found in his childhood memories of his mentally ill mother. As a young boy he would sit for long periods of time locked in her room until after several attempts she eventually escaped and took her own life in the River Sambre in 1912. The claustrophobic nature of the expanded apple sucking the space from the room in the present work could certainly be linked to this experience, as the artist attempts to eliminate what was once his normality with an alternate reality, leading us also to question what, or who, is hidden behind the apple.

As a study for two seminal paintings from 1952 and 1958 titled La chambre d'écoute, or The Listening Room, the present work sits firmly within Magritte's seminal mature period and its importance as a study for one his most recognisable works cannot be understated, with both finished paintings now residing in public collections in the US and Switzerland.

The nature of Magritte's studies for his paintings offers the viewer an intimate insight into the bubbling mind of this Surrealist master like no other. Whilst the present work appears to be a study for the aforementioned paintings, we are immediately drawn to the highly finished nature of the draughtsmanship and the considered ink line, which, coupled with the artist's signature in the lower right corner, offers an elevated position for the work and almost allows it to be placed within The Listening Room series as a finished work in its own right.